Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo and the art of revolution

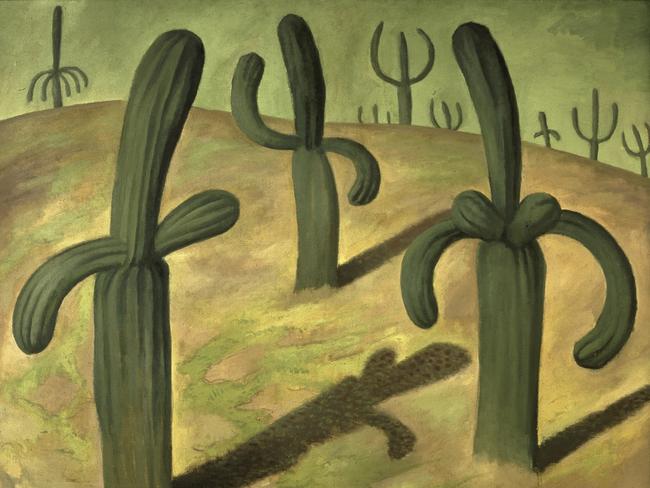

Some of Mexico’s most celebrated artists were part of a scheme to paint vast murals depicting the country’s past, present and future.

Mexico City is a virtual art gallery when you know where to look. Thanks to the muralism movement in the early 20th century, artists including Diego Rivera, David Sequeiros and Jose Orozco painted large-scale murals depicting Mexican society and history in public buildings. Walls inside schools, hotels, government buildings and the National Palace became, in effect, their canvas.

The murals depict scenes from the pre-Columbian civilisations to the Spanish conquistadors, the Mexican Revolution and contemporary society. But none is as strange as the mural by Rivera now housed in Mexico City’s opera house, the Palacio de Bellas Artes. Man, Controller of the Universe is a vision of two halves. On the left it depicts the march of fascism, decadent capitalists and the exploitation of working people; on the right, the united people of a collectivist society, and the heroes of communism including Marx, Lenin and Trotsky. In the middle is the Controller, the archetypal proletarian driving the engines of science and space exploration.

The truly strange aspect of this vast didactic painting, about 11m across, is that it originally was commissioned for one of the seats of world capitalism, the Rockefeller Centre in New York. By the early 1930s Rivera was a celebrity in Mexico and in the US: he’d already had a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art and completed a mural cycle in industrial Detroit.

The mural for the Rockefeller Centre, originally titled Man at the Crossroads, was completed in 1933 but Nelson Rockefeller, the future vice-president, objected to the inclusion of Lenin’s portrait. Rivera refused to remove it and the painting was covered over, later destroyed.

The mural in the Palacio de Bellas Artes is a reconstruction of the Rockefeller painting, and Lenin is featured prominently.

“Imagine this painting in Manhattan,” says my guide, Aldo Solano Rojas. “This isn’t just a Mexican story, this is talking to the American people. I love seeing the Kremlin and the skyscrapers in opposition. It’s so smart. He knew he wanted to provoke people.”

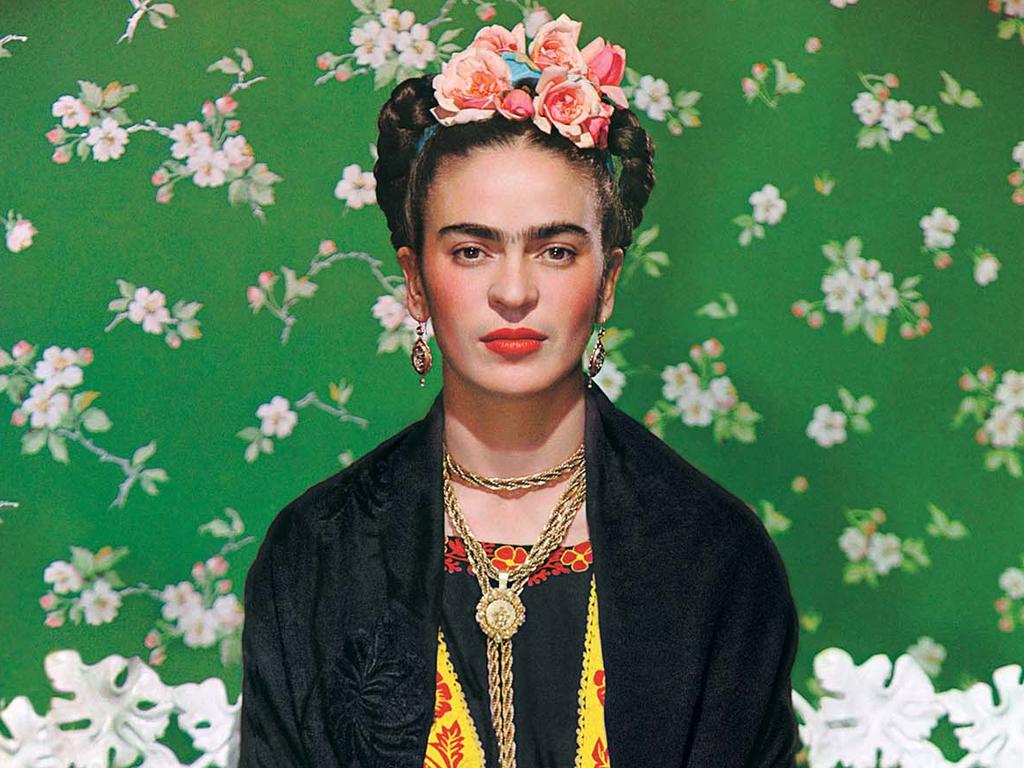

Our tour of Mexico City’s murals is a prelude to the exhibition of Mexican art opening at the Art Gallery of SA on Saturday. Frida and Diego: Love and Revolution showcases paintings by Rivera and his wife, Frida Kahlo, as well as by leading modern artists such as Siqueiros, Rufino Tamayo and Maria Izquierdo.

Kahlo is the artist of the period most widely recognised outside Mexico today. But from the 1920s, Rivera and other muralists were famous for their visually potent representations of Mexican society; past, present and future.

We begin our tour in the central plaza of Mexico City, the Zocalo, bordered on one side by the baroque Metropolitan Cathedral and on another by the National Palace. It’s early spring when I visit – the jacaranda trees are blooming abundantly – and by mid-morning it’s already hot. Mexico City is at an elevation of 2240m – a fraction higher than Mt Kosciuszko – and this, together with air pollution, leaves me feeling heady and short of breath, especially when climbing the stairs of government buildings to see the murals.

The birthplace of Mexican muralism is the Colegio de San Ildefonso where Rivera painted his mural, La Creation, in the auditorium. It’s also where Kahlo first met Rivera, when she was a student at the school. Rivera had been studying art and working in Europe, and returned to Mexico with ideas and techniques he learned from Renaissance frescoes in Italy. He applied fresco technique and mural storytelling to narratives of Mexican society and politics, sponsored by education minister Jose Vasconcelos.

One of Rivera’s largest mural cycles is in the nearby Secretariat of Public Education. His frescoes are a celebration of Mexican culture and its revival through the Mexican Revolution. There are scenes of people going about their work in markets, mines, factories and schools. Solano points out Rivera’s “trinity” of the Mexican Revolution, being the soldier, farmer and factory worker. One of the frescoes, called The Arsenal, includes a portrait of Kahlo, dressed as a factory worker and distributing rifles and bayonets.

“It’s trying to recruit people to the movement,” Solano says. “Frida is dressed as a factory worker, with a red star on her shirt. At the time she was not a famous artist, but she is depicted as an empowered woman. She is part of this idea of the Mexican Revolution.”

Elsewhere in the cycle are Rivera’s depictions of the capitalist class, in panels with titles such as The Orgy and Death of the Capitalist. In one, fashionably dressed women and men are at a banquet where the only food on their plates is gold. Another picture has JP Morgan, John D. Rockefeller and Henry Ford sitting around a table, obsessed with their stock prices from a ticker-tape machine.

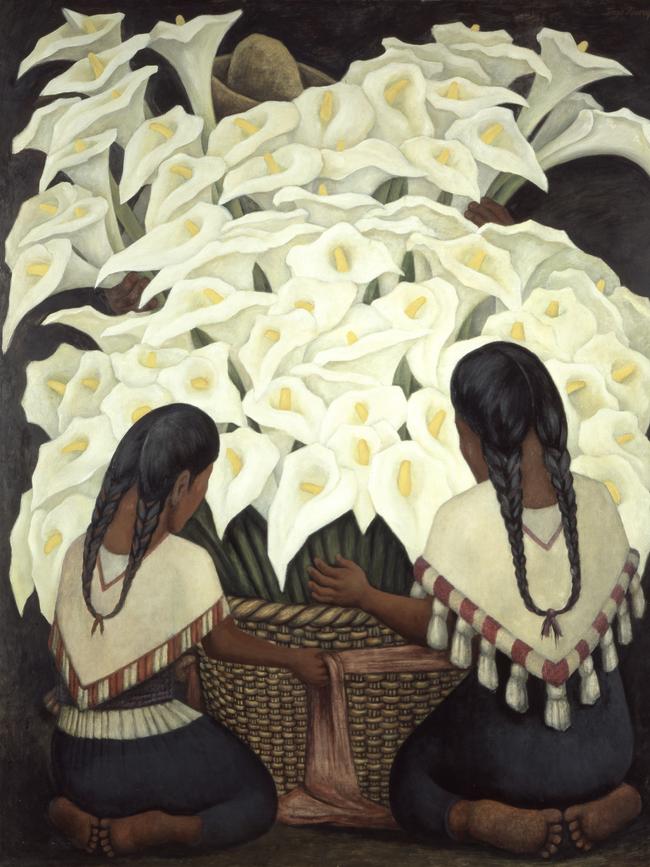

Rivera worked with assistants to paint the frescoes, but the scale of his output across hundreds of square metres is nonetheless astonishing. He developed a visual language that simplified human figures but gave them solidity and dignity, as can be seen in his pictures in the AGSA exhibition, The Healer and Calla Lilly Vendor.

“It was my desire to reproduce the pure, basic images of my land,” Rivera wrote. “I wanted my paintings to reflect the social life of Mexico as I saw it, and through my vision of the truth to show the masses the outline of the future.”

His simplified style enabled him to build up compositions of great scale and complexity. Another example is his 1946-47 mural, Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Central, a fantasy pageant of figures in the Alameda, a park in Mexico City and the oldest public park in the Americas, established in 1592.

It includes portraits of historic figures including Hernan Cortes, Maximilian I, the short-lived Habsburg Emperor of Mexico, and Porfirio Diaz, the dictator overthrown by the Mexican Revolution.

There are artists and intellectuals, revolutionaries and peasants. Rivera is shown in a self-portrait at age nine, wearing a straw boater and holding hands with La Calavera Catrina, a female skeleton figure popular in Day of the Dead parades. Kahlo can be seen in a portrait behind them.

The painting was commissioned for the Hotel del Prado. After the hotel was damaged in the 1985 earthquake in Mexico City, it was painstakingly moved to a new location next to the Alameda, in a specially built museum.

The Mexican muralists, especially Rivera, were celebrated in their lifetimes and were influential on other artists, including in the US.

“They modernised the fresco technique, and their idea of massiveness was very influential on the Abstract Expressionist artists,” Solano says. “Jackson Pollock was very influenced by Siqueiros and went to study with him. And Siqueiros later used industrial paints. He forgot about plaster and started to use car paint, and that was very influential for Jackson Pollock. Mark Rothko was very influenced by the massiveness of the wall that involves you. This was very important for North American art as a whole.”

We end our mural tour with the cycles Rivera produced for the National Palace, including The History of Mexico. Teeming with figures, the mural describes the mythology and culture of the Aztec civilisation, the arrival of Cortes and the conquistadors, the destruction of local customs and beliefs with missionary Christianity, and finally the triumph of Mexican socialism.

Mexico City’s murals serve a didactic function similar to that of the famous frescoes of Christian narrative by Giotto and Michelangelo in Italy, and to the bracing images of triumphant farm and factory workers produced in the Soviet Union. They reinforce a particular ideology, different in each case, but intended to instruct. Rivera’s great achievement was to fulfil the polemical purpose of his murals while investing them with humanity and humour – something of a rare commodity in socialist realism.

Not in question is the mural’s effectiveness as a form of visual communication. The figures in Rivera’s vast murals have a way of lodging themselves in the memory, even if the people they represent are long forgotten and the causes they fought for obscure.

Frida & Diego: Love & Revolution is at the Art Gallery of SA, Adelaide, June 24-September 17. The writer travelled to Mexico City courtesy of the AGSA.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout