Artist Frida Kahlo’s personal world of colour, character and pain

When she died, Frida Kahlo had produced fewer than 150 paintings and one solo exhibition. Why is she bigger than ever?

You don’t need to be an expert on Mexican art to recognise Frida Kahlo. You know her when you see her. In her short and eventful life she painted fewer than 150 paintings, more than a third of them self-portraits. In them, she lets the viewer into her personal world of love, abundant zest for life, and excruciating pain.

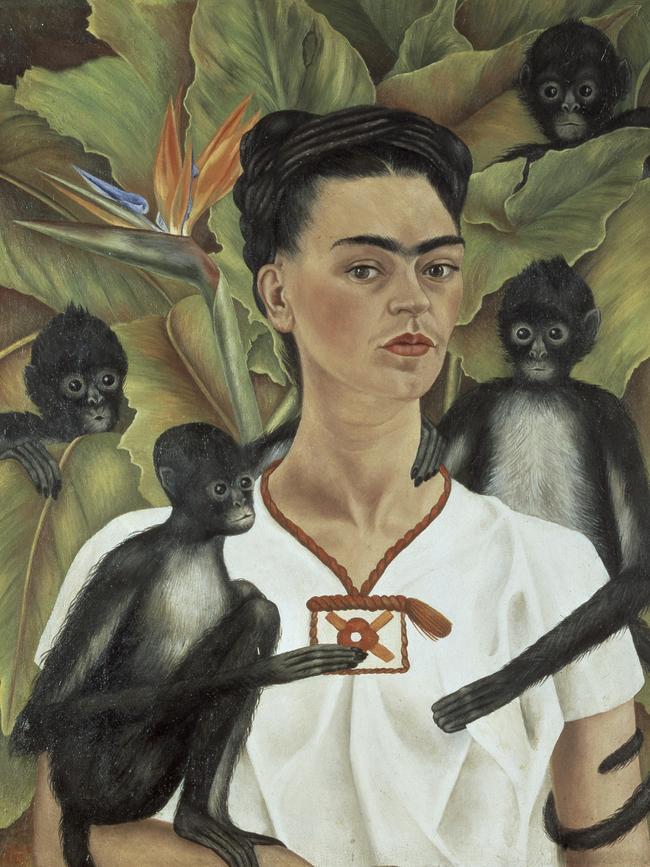

She’s famous, of course, for her facial hair – the faint moustache and monobrow that she exaggerated for effect in her paintings – and her colourful Mexican folk costumes. She depicted herself with a personal iconography that included pet monkeys, her broken body and surgical supports, even an image of her miscarried foetus. All the while she stares out of her paintings with dark, penetrating eyes.

“She turns the gaze back on herself,” says Tansy Curtin from the Art Gallery of South Australia.

“She invites us, as the audience, to engage with a very unflinching version of herself. It encourages us to think about the psychological elements in her work – but also about our own motivations: who we are, and how we see ourselves, and how we want to see ourselves. That’s why she resonates so strongly with us today. Why is it that so many years later, with a small oeuvre of works, she is such an important figure in the history of art?”

It is rare for Australians to see Kahlo’s work first-hand. Many of her paintings are held in two major collections of Mexican art in Mexico. Australia’s public collections don’t have any. But this year, Australians will have two different opportunities to explore Kahlo’s life and art.

The AGSA, where Curtin is curator of international art, is hosting a major exhibition of Mexican art that focuses on Kahlo and her husband Diego Rivera. Opening in June, Frida & Diego: Love & Revolution will include more than 150 works by important Mexican artists, mostly unknown to Australian gallery-goers.

And this week, the Sydney Festival will open Frida Kahlo: The Life of an Icon, a portrait of the artist told through projected images, virtual reality and holograms, presented in the vast space of The Cutaway at Barangaroo. While not a conventional art exhibition, the “immersive biography” draws on archival images of Kahlo to paint a picture of her life and legacy.

Jordi Sellas, whose Barcelona-based company Layers of Reality has produced the multimedia experience, says the show poses a question: how did Kahlo become a pop-culture icon? When she died in 1954, at age 47, she had had only one major solo exhibition. And yet, like Vincent van Gogh who died some 60 years earlier, the strength of her artistic personality and the dramatic facts of her life propelled her from obscurity into a wider public consciousness.

“Why is Frida Kahlo in 2022 a bigger and more recognised artistic figure than she was in the 1950s when she died?” Sellas says. “Nobody knew her in the 1950s. The only solo exhibition she had was the exhibition months before she died. The other exhibitions she did in the US and France were collective exhibitions with other Mexican artists. She was popular, but not popular like she is today. Why is she today that icon?”

Kahlo was born in Mexico City in 1907. Her father, Guillermo Kahlo (originally Carl Willem), was a German-born photographer who emigrated to Mexico where he had a successful career.

Kahlo’s mother, Matilde, had Spanish and indigenous Mexican heritage. Kahlo later changed her date of birth to 1910, aligning her with the start of the Mexican Revolution, a 10-year civil war that also saw an explosion of Mexican art and culture.

Kahlo’s health problems started in childhood when she contracted polio as a six-year-old, leaving her with one leg shorter than the other. When she was 18 she was involved in a road accident that all but claimed her life. She was on a bus home from school when it collided with an electric tram. She suffered horrific injuries. A metal handrail impaled her through the abdomen, breaking her pelvis, spine, collarbone, ribs, right leg and right foot. She spent a month in hospital, her shattered body encased in a box like a coffin.

“She was a young woman in her prime,” Curtin says. “She had an accident between a bus and a trolley car or what we would call a tram. A metal rod pierced her uterus and broke her spine in three places. She was very badly hurt. Over the course of her life she had multiple operations on her spine – one of her most famous paintings is Broken Column, which talks about that part of her body as failing her. She spent a lot of her life in and out of hospital, in and out of wheelchairs and in and out of bed.”

Kahlo’s artistic practice was circumscribed by her frail physical health and experience of pain. Frequently bedridden, and flat on her back, she painted at a special easel, with a mirror positioned above the bed so that she could see her work. Her limited mobility at those times also affected her choice of subject. The most available subject was herself, and she turned her gaze inward to self-portraiture and personal symbolism. Her work variously has been described as magic-realist and surreal – Andre Breton attempted to recruit her to surrealism but Kahlo rejected that appellation – combined with naive or folk art.

“She studied at art school, but she developed a particular style,” Curtin says. “When you see her work among her contemporaries, there is a Mexican aesthetic. She was not operating outside the artistic milieu of the period, she was working with other artists and they were sharing ideas.

“For Frida, painting en plein air, painting outside, was not an option. It was the internal life that she turned to, because that’s what she had access to.”

The other major force in her life was her tempestuous relationship with Diego Rivera. Already a celebrated mural artist, and 20 years Kahlo’s senior, Rivera met Kahlo when she was still a schoolgirl. To their families they were a mismatched pair, an “elephant and a dove”. Kahlo was fragile and petite; Rivera was fat and towered over her. Hayden Herrera, in her very readable biography of Kahlo – it was made into the 2002 film Frida, with Salma Hayek – refers to Rivera as frog-like. Despite appearances, Curtin says, Rivera was a hugely popular artist and a charismatic figure.

Both of them had affairs, Kahlo with men and women. One of her most celebrated lovers was Leon Trotsky, in exile from Stalin’s Soviet dictatorship. A long-term relationship was with Nickolas Muray, the fashionable photographer who produced striking colour portraits of her.

Sellas says the many dimensions of Kahlo’s personal, political and artistic identity – female, bisexual, disabled, indigenous, communist – align with modern sensibilities about minority groups, which helps to explain the contemporary fascination with her.

“In cities all around the world, you see people wearing Frida’s face on T-shirts, and defending different things: the (LGBTQI) Pride Day, also defending the small languages in the world, defending the new ways to create art,” he says.

“Frida’s figure is more centred in how we need to protect and defend minorities. Minorities can be a cultural minority, a physical minority, a sexual orientation minority … Not in a sad way, but in a powerful way.”

The exhibition coming to Adelaide is from the Gelman Collection, assembled by Jacques Gelman, a Russian emigre and film producer, and his wife Natasha. It includes 10 paintings by Kahlo, as well as works on paper and paintings by Rivera other artists in their circle. A smaller selection from the Gelman Collection came to the Art Gallery of NSW in 2016.

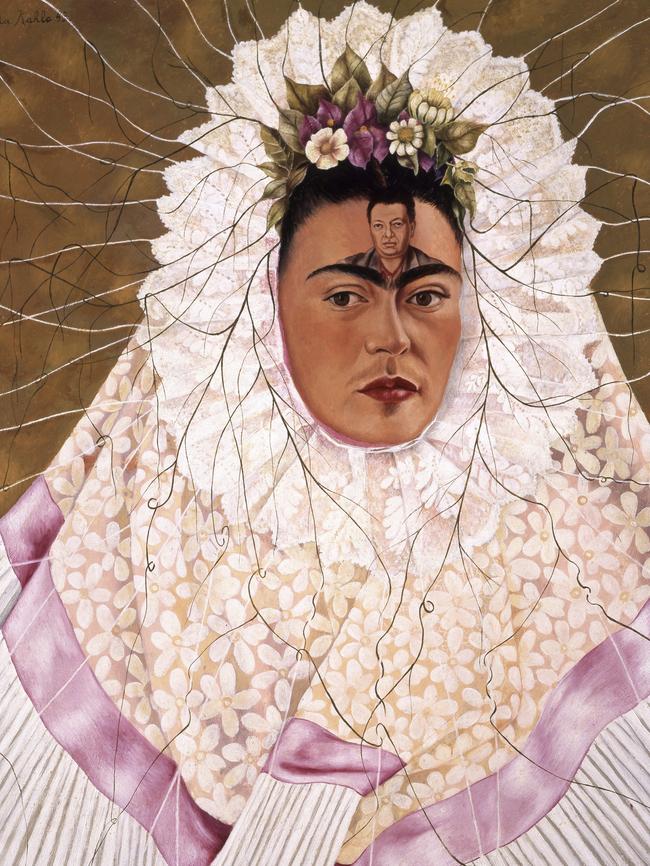

Among the compelling self-portraits of Kahlo in the exhibition is the famous image of her in traditional Mexican dress, Diego on My Mind (Self-Portrait as Tehuana), from 1943. Her face is framed with starched lace from Tehuantepec, Oaxaca, and her forehead stamped with Rivera’s image.

In another painting, Self-portrait with Braid, Kahlo wears what appears to be an enormous pretzel on her head. As Curtin explains, it’s a braid of her own hair, which she cut off after an argument with Rivera. “The story of that work is that Frida and Diego had a very big fight, and he was a big proponent of her wearing traditional Mexican costume – so she cut her hair off, and stuck it on her head,” Curtin says. “It becomes a narrative about their relationship and her exerting her power in that relationship.”

Other paintings refer to fertility and her desperation to have a child with Rivera. She had several pregnancies but the injuries she suffered when she was 18 meant she was unable to carry a baby to full term. A luscious still life of cut watermelon and pawpaw, the exposed ripe flesh revealing the seeds inside, has the title The Bride Who Becomes Frightened When She Sees Life Opened. A lithograph from 1937, called Frida and the Miscarriage, is a kind of anatomical self-portrait with the sad little figure of a foetus’s head and torso.

“(Fertility) is an important idea in Frida Kahlo’s work because she couldn’t have children,” Curtin says. “She had a miscarriage when she and Diego were in Detroit, and that formed an important part of her body of work – a great tragedy for her. It’s that idea of female awakening – the fruit is about fertility and reproduction. But it’s also incredibly Mexican: this wonderful arrangement of tropical fruit that you can imagine seeing in street stalls in Mexico City.”

Works by Rivera in the exhibition, while not examples of his murals, demonstrate his expression of Mexicanidad, the authentic national identity as seen in folk art, local occupations and customs, plants and animals. The theme is carried through in works by artists such as Maria Izquierdo and Miguel Covarrubias.

The show is bookended by photographs, the earliest by Frida’s father Guillermo Kahlo – commissioned to document Mexico’s built environment – and the most recent by Patti Smith. Smith, like others, had made the pilgrimage – it seems the right word – to Kahlo’s house in Mexico City, the Casa Azul, and to photograph Kahlo’s bed, crutches and back brace.

Some of that atmosphere, the Kahlo mystique, is evoked in the Sydney Festival experience, Frida Kahlo: The Life of an Icon.

Unlike other son et lumiere shows about van Gogh and Monet that employ wall-size projections of their art works, the Kahlo presentation does not feature her paintings. Instead, it uses archival images of Kahlo, as well as music and installations – such as a little shrine, and a representation of her bed – to give emotional colour to her life story.

Sellas, from Layers of Reality, says his company is developing new kinds of cultural experiences at the intersection of art and technology – including 3D projection mapping, holograms and virtual reality – that are showcased in the Kahlo show.

“There’s an eight-minute experience where you start by sitting on Frida’s bed, feeling how she felt,” he says of the VR program. “And then you start a trip around Mexico in the beginning of the 20th century, and you go inside the paintings and the symbols that she used. It’s a big challenge for us, to create a virtual reality experience that can be enjoyed by children and by older people.”

The immersive experience includes examples of traditional Mexican dress, a specially commissioned soundtrack and a hologram presentation that explains how Kahlo’s tragic accident happened.

AGSA’s Curtin, who has also visited the Casa Azul, says she was touched by the domesticity of the place, its lived-in sense of homeliness. But it was also evident that Kahlo is regarded as almost a sainted figure, where objects associated with her are kept like relics. If that sounds a little ghoulish, it also helps explain the fascination with Kahlo as an artist and cultural icon.

“You see her crutches and her wheelchair and prosthetic leg – they really make Frida Kahlo so human,” Curtin says. “There is tragedy in Frida’s life, but also resilience and transcendence of tragedy.”

Frida Kahlo: The Life of an Icon is at the Cutaway, Barangaroo as part of the Sydney Festival, January 4-Febuary 12. Frida & Diego: Love & Revolution is at the Art Gallery of South Australia, June 24-September 17.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout