Frida Kahlo exhibition coming to Art Gallery of SA

It’s difficult not to become mesmerised by the Mexican artist, who embraced sexuality and faced pain head-on in both her life and art.

The Casa Azul in Mexico City is the family home where Frida Kahlo was born, lived with her on-off-on-again husband Diego Rivera, and where she died too young at 47. To reach it is a drive of about 40 minutes, on a good day in one of the world’s busiest cities, along the freeway south of the Zocalo in the city centre to the leafy residential streets of Coyoacan, the place of coyotes. When I visit in late March, the northern spring, the jacaranda trees are showering the footpaths with their gorgeous purple rain.

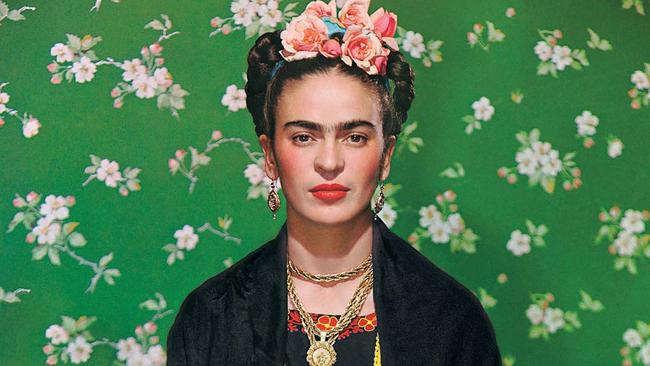

The Casa Azul, or Blue House, is a different shade, painted deep cobalt blue. It now serves as a house museum and, for some, the temple shrine of the Kahlo cult. Before the doors open a line of visitors has stretched around the corner. Street vendors are selling Kahlo trinkets: T-shirts, dolls and other souvenirs printed with her famous dark eyes, moustache and monobrow.

Once inside, people are visibly moved by their encounter with Frida. You can see the bed where she painted, flat on her back, the result of the devastating injuries she suffered in a road accident when she was a teenager. A mirror mounted to the underside of a canopy over the bed allowed her to see what she was painting. There are examples, too, of her magnificent Mexican costumes, velvet wraps and richly embroidered shawls, as well as her crutches and surgical corsets. She sublimated her suffering into her art – especially her self-portraits – and the intensity of it all is undeniable. It’s a relief to step outside into the sunshine and spend a quiet moment in the courtyard among the cactuses and succulents.

Indeed, the Casa Azul is one of the few places where devotees can go the full Frida. Elsewhere, her legacy is dispersed. Most big art museums have only one or a few of her paintings. Australian public galleries have none. Her body of work is concentrated in two private collections that were assembled by Dolores Olmedo and by Jacques and Natasha Gelman. The result is that, while representations of Frida and Diego seem to be everywhere in Mexico City – from earrings, cushions and votive candles to their names on the awnings of cantinas – it can be hard to get a grip on who they were, and what they were about. That lingering image of Frida’s monobrow has a long after-life.

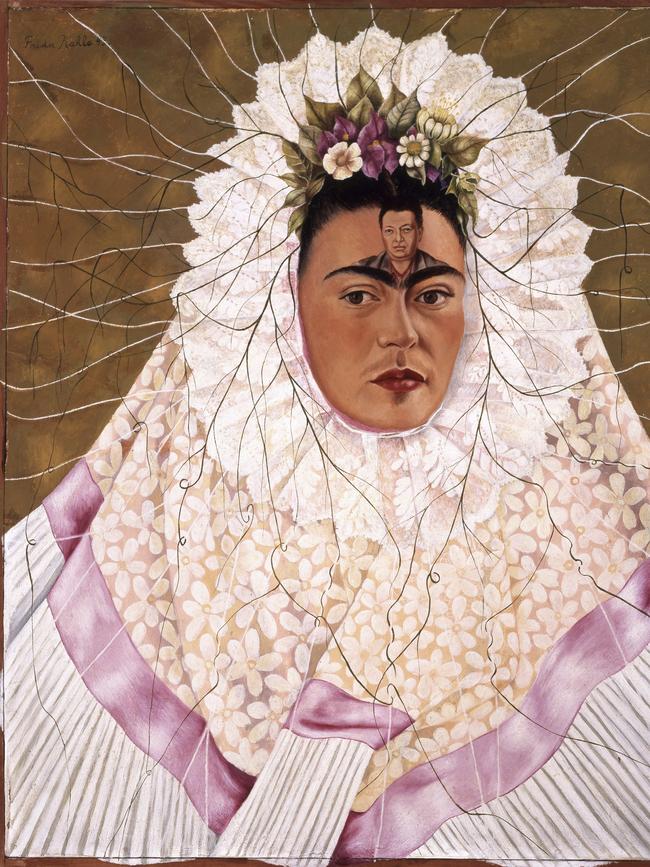

Fortunately, Australian gallery-goers have the opportunity to see a substantial collection of paintings by Kahlo, Rivera and other Mexican artists of their circle in Frida & Diego: Love & Revolution, the headline winter exhibition at the Art Gallery of SA. From the Gelman collection, it will include 150 works, including paintings, works on paper, photographs, video and period costumes. Significantly, it has 10 paintings by Kahlo, including one of her emblematic self-portraits, Diego on My Mind, with the image of her husband literally stamped on her forehead. The Gelman collection previously has loaned art to Australia – most recently to the Art Gallery of NSW in 2016 – but this is the most comprehensive exhibition from the collection of Mexican artists.

Robert Littman, custodian of the Gelman collection, was involved with planning an exhibition at the Grey Art Gallery at New York University in 1983 that paired Kahlo with actor and photographer Tina Modotti. Across the intervening 40 years he has seen an explosion of interest in Kahlo.

“When we did the Frida Kahlo exhibition in New York in the ’80s, not that many people knew who Frida Kahlo was,” he says at his home in Cuernavaca, south of Mexico City. “The cognoscenti knew who Frida Kahlo was. But beyond that, the general public didn’t. Now, with all of this imagery – and being compared with the Mona Lisa, and things like that – it just grows and grows.”

The fascination has been driven, in part, by Julie Taymor’s movie Frida – starring Salma Hayek, with Alfred Molina as Rivera and Geoffrey Rush as Leon Trotsky – which in turn was based on Hayden Herrera’s excellent biography of the artist, published in 1983. Women were inspired by her feminism and courage. Her frank sexuality made her a gay and lesbian icon.

“Women are interested in her life, and her troubles and her conflicts,” Littman says. “And the whole openness of society – Frida experimenting sexually, which in the ’40s would have been condemned. I think women and gays certainly helped her reputation. Museums know that this will be a magnet for people, especially young people – they love the mystique of it. And you can’t see (the paintings) everywhere. How many museums have a Frida Kahlo?”

Kahlo once said there were two defining events in her life. The second was the accident, when she was 18, that almost claimed her life and caused her unimaginable suffering afterwards.

In 1925 she was on a bus home from school in Mexico City when the bus collided with an electric tram. Her injuries were horrific. A metal handrail impaled her in the abdomen, breaking her pelvis, spine, collarbone, ribs, right leg and right foot. She spent months in hospital, her shattered body coffined in a cast. For years afterwards, she put herself through surgical procedures – advanced for the time, primitive by today’s standards – in an attempt to fix her damaged spine. Her forbearance, and the elegant image she presented to the world as she endured years of pain, is part of her legend.

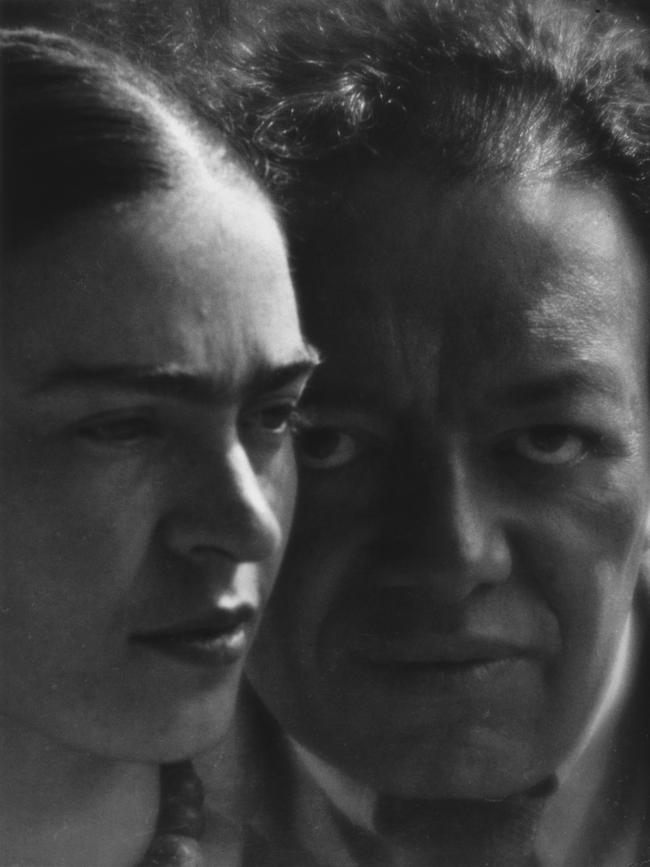

The first accident of her life – and which she said was by far the worst – was meeting Diego Rivera. She was just 14 when she first met the older artist, who had come to her school, the Colegio de San Ildefonso, to paint a mural in the auditorium. Rivera at the time was becoming a celebrity, associated with the Mexican Revolution and its elevation of traditional Mexican culture.

The painting he made across the back of the stage in the school theatre, La Creation, is a strange amalgam of Christian and Mexican symbolism, representing the renaissance of Mexican culture and becoming, in effect, the birth of the muralism art movement, of which Rivera was the leader. From the 1920s, Rivera and other artists were commissioned to paint large-scale murals in public buildings in Mexico City – painted polemics on the virtues of Mexican communism and the decadence of capitalist gringos to the north. The Adelaide exhibition, while it does not include actual murals, has Rivera’s paintings The Healer and Sunflowers, which demonstrate his idealised portrayal of Mexican peasants, and the simple figurative style he also used in his mural frescoes.

Frida and Diego certainly made an odd couple when they eventually formed a relationship and married in 1929. He was 21 years older, fat, and towered over the petite Frida. Even to their families they were a mismatched pair, an “elephant and a dove”. And their relationship was tempestuous. Both had other lovers, Frida with men and women, including Trotsky, photographer Nickolas Muray and, it’s been suggested, with Georgia O’Keeffe. Rivera had an affair with Frida’s sister. Like a Latino Liz Taylor and Richard Burton, they married, divorced, and remarried.

They were united in their fervour for Mexico and for communism. What’s fascinating is how they used art and culture – not only in their paintings, but in their manner of dress, and the furnishings in their home – to telegraph their political allegiances, in which their communism was closely aligned with indigenous and working-class people.

The image of Kahlo wearing Mexican folk dress is so familiar that it’s easy to overlook how radical it must have seemed. Kahlo was part Mexican. Her father, Carl Wilhelm (later Guillermo) Kahlo, was a photographer from Germany. Her mother, Matilde Calderon y Gonzalez, was mestiza, with Spanish and indigenous Mexican heritage. Kahlo, who was born on July 6, 1907, told people she was born in 1910, aligning her birth with that of the Mexican Revolution which started that year.

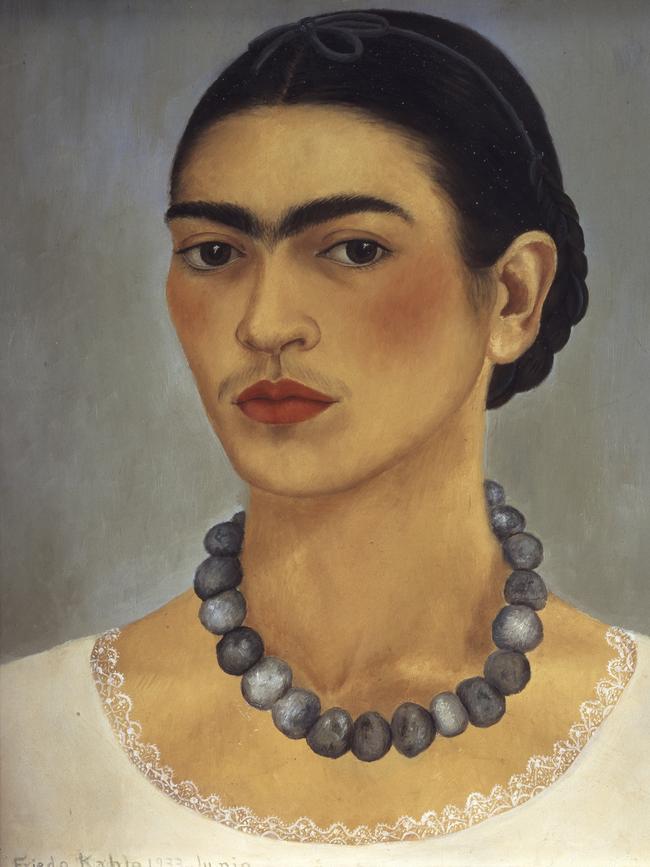

When she was in her early 20s, she started to wear folk costumes and chunky jewellery from different parts of Mexico, and depicted herself wearing those outfits in her paintings and in photographs. She certainly had a sense of style – later, she’d be photographed for Vogue – but the costumes were anachronistic and possibly provocative to middle-class sensibilities. Even her famous monobrow and moustache were exaggerated for effect in her paintings. Compare the fully joined brows in her 1943 picture, Self-portrait with Monkeys, with those in one of Nickolas Muray’s photographs of Kahlo in Mexican costume.

In their home, Kahlo and Rivera advertised their Mexicanidad, or Mexicanness. The Casa Azul has displays of their homewares and furnishings, including their simple pueblo-style wicker chairs and glazed earthenware pots and jugs in the kitchen. Frida had a substantial collection, too, of ex-voto pictures: small paintings on copper that were bought by peasants as prayers of thanks – for a life saved from drowning, say, or for the return of a missing cow. These touching, utterly captivating examples of Mexican folk art Kahlo used as a model for her own naïve style of painting that drew on her personal mythology and images.

An example of the style in the Adelaide exhibition is Kahlo’s Self-portrait on Bed, 1937. Like the ex-voto pictures it is painted on metal, and depicts Kahlo sitting on an austere bed with the doll-like figure of a baby sitting upright next to her. Kahlo had fallen pregnant in 1932, and at first was given medication to induce an abortion; she then decided to carry the child and later had a miscarriage. She was ambivalent about pregnancy and motherhood but the painting poignantly expresses her feelings about what might have been. Another picture, Frida and the Miscarriage, a lithograph, is like an anatomical drawing, showing Kahlo’s body and reproductive organs, and a tiny foetus.

Even a still-life picture, such as The Bride who Becomes Frightened when she Sees Life Opened, is suggestive. It is a painting of tropical fruit arranged on a table: watermelons cut open to reveal their pink pulp and seeds, plump avocados and luscious papaya. The title and the symbolism are unmistakeable, the ripeness of the fruit alluding to fertility and longing.

All of Kahlo’s preoccupations come together in her self-portraits: her devotion, even obsession, with Rivera; her cultivation of a personal iconography and Mexicanidad; her proud bearing, even as she endured incredible pain.

Self-portraiture was her genre because she was her most available subject. Frequently bedridden, she was unable to paint outdoors. And often there is a story behind her paintings. Her pretzel hair-do in Self-portrait with Braid followed an argument with Rivera when she threatened to cut off her hair – and did.

One of her strangest pictures is The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth (Mexico), Diego, Me and Senor Xolotl. Kahlo said that her art was not surrealist, despite attempts by Andre Breton to recruit her to the cause. (A “ribbon around a bomb” was how the founder of surrealism described her pictures.) But this painting more than others has the dreamlike imagery that is associated with surrealism. In it, a youthful-looking Kahlo embraces a child-man figure of Rivera. They in turn are embraced by the green figure of an earth goddess, and all three figures are held in the arms of a ghostly universal spirit. Senor Xolotl is Kahlo’s pet dog, named for the legendary canine of Aztec mythology. Painted in 1949, towards the end of her life, the image is imbued with a kind of personal spirituality, uniting Kahlo and Rivera in a universal, female godhead.

Tansy Curtin, curator of international art at the Art Gallery of SA, says Kahlo’s portraits exert a fascination because they invite a direct communication with the viewer. “She invites us, as the audience, to engage with a very unflinching version of herself – she gazes back at us from the canvas,” Curtin says.

“But by laying herself bare, we the audience are essentially laying ourselves bare. We see ourselves in a way that we perhaps don’t show to people around us. It encourages us to think about the psychological elements in her work – but also our own motivations: who we are, and how we see ourselves, and how we want to see ourselves.

“For me, that’s why she resonates with us so strongly today, and why – years later, and with a small oeuvre of works – she is such an important figure in the history of art.”

So popular is Kahlo and so rare the opportunity to see her paintings in number that the Gelman collection is almost permanently on tour. It will be rested after the Adelaide season.

It has a fascinating provenance. Jacques Gelman was a Jewish émigré from St Petersburg who settled in Mexico and went into a filmmaking partnership with Mario Moreno, the hugely popular Mexican comedian. With his Czech wife Natasha, Gelman assembled substantial collections of pre-Columbian, modern Mexican, and modern European art. Paintings from their collection by Bonnard, Picasso, Braque and others – including Matisse’s celebrated portrait The Young Sailor II – are now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Gelmans commissioned paintings directly from artists, including from Kahlo and Rivera. Rivera’s portrait of the glamorous Natasha has her reclining on a sofa, the shape of her figure-hugging white gown, split to the knee, mirroring the forms of oversize calla lilies behind her.

Other artists in the collection show the breadth of Mexican art from the first half of the 20th century, starting with photographs of historic Mexican architecture by Frida’s father Guillermo Kahlo, and art photography by Manuel Alvarez Bravo and his wife Lola Alvarez Bravo. David Siqueiros – an influential muralist alongside Rivera, and would-be assassin of Trotsky – is represented with a sombre self-portrait. Paintings by Rufino Tamayo, Miguel Covarrubias and another important female artist of the period, Maria Izquierdo, help round out the collection. Together they form a picture of Mexican modernism that was in conversation with international trends but also firmly rooted in the local vernacular and preoccupations.

Still, it’s hard to turn one’s gaze from Kahlo, and other artists in the exhibition duly oblige. Muray’s colour portraits are emblematic of Kahlo’s dress and style, while later photographers including Patti Smith – her images include the artist’s bed, crutches and surgical supports – speak to an almost morbid fascination with her endurance and pain.

Taken together, it’s an irresistible package, an explosive combination of the kind we readily recognise: intimately confessional, culturally sophisticated, stunningly presented. A ribbon around a bomb, indeed.

Frida & Diego: Love & Revolution is at the Art Gallery of SA, Adelaide, June 24-September 17. The writer travelled to Mexico City courtesy of the AGSA.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout