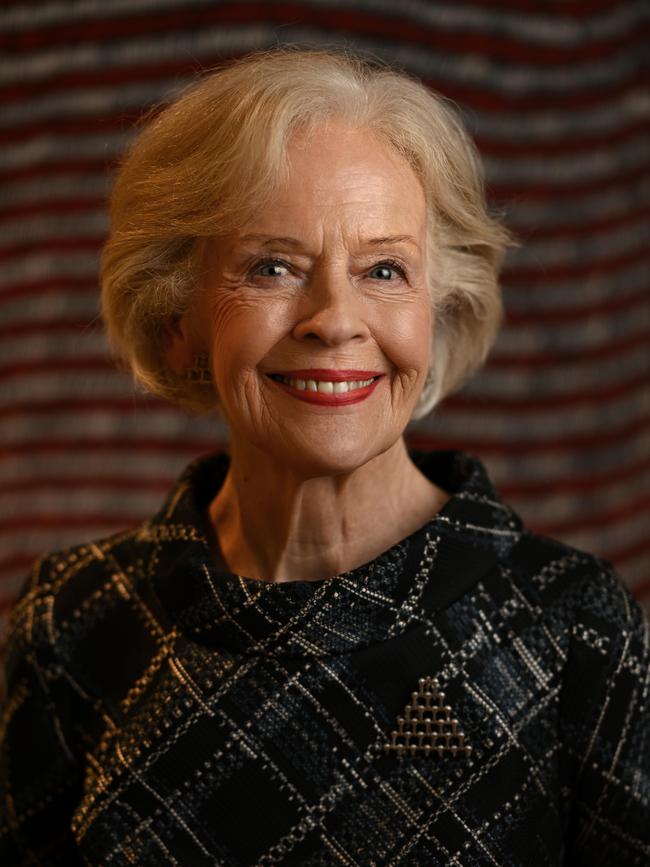

Quentin Bryce reflects on ‘the enormous adjustments of getting older’

In a long career, she’s experienced the best and toughest of Australia. But nothing prepared former governor-general Quentin Bryce for her greatest loss.

Quentin Bryce will tell you many things about ageing: a discernible sense of caring and feeling more deeply; the increase in confidence; the importance of a healthy diet, notwithstanding her aversion to a fashionable vegetable.

“Everybody I know is eating kale, well I don’t like kale at all,” she declares triumphantly.

At 81, she talks about the challenges of feeding just one – “who’s going to cook a wonderful soup for yourself?” – and when she mentions her weekly afternoons with her seven-year-old granddaughter, the youngest of her 12 grandchildren, her voice skips with joy.

But she finds it almost impossible to discuss one of the most dramatic changes to her latter life: the death in 2021 of her husband, Michael.

“It’s a huge adjustment,” is all she is able to utter initially of a subject that is etched into her heart but of which she rarely speaks publicly.

It’s not the solitude of widowhood with which the former governor-general struggles.

“One of my sisters said to me, ‘Of course you’ve gone from cocoon to cocoon; you’ve never lived on your own’.” In fact she quite enjoys being on her own in her Brisbane home, with its garden awash in spring’s colours.

But the absence of a 60-year-long beloved presence in her life has left a lingering wound, a loneliness that often precludes words.

“It’s right at the heart of so many people’s lives, especially for women,” she says eventually. “The enormous adjustments of getting older and all the things you have to learn about and know about for yourself, and caring for people who are ageing in your family, especially your spouse. I was married for nearly 60 years. It’s an enormous adjustment getting older, going into your 80s and how you live your life in a very different environment.”

Or, as she also says: “Women have mostly put themselves last on the agenda, and now they are the agenda”.

An important aide for Dame Quentin, after a long public life, is that she has returned home to a ring of local love.

“I’m a grassroots person,” she says. “I think neighbourhood is an enormously important and precious part of life.”

From weekend drinks to collating her daily newspaper delivery, her neighbours are an intrinsic part of her life and its sense of security.

“I know they are there always and I have their phone numbers,” she says. “When my husband was ill, it’s neighbours you would ring … It would be an emergency situation and I would say ‘can you come?’ and they did.” Even though she is close to her five children, most of whom live nearby, “these are people who live two doors away”.

It’s that neighbourly support that she nominates as a key to ageing well.

“I don’t think you have to present a picture that everything is wonderful, because it’s not. “There are challenges in ageing,” she says, alluding to the deaths of friends and relatives that invariably mark this period.

While she lives with that sadness, she also embraces the benefits of being older.

“You feel things more deeply and you care more deeply, you think about things more deeply. People often say ‘oh it must be wonderful now you have more time’. You have less, so what you do is you distil things that matter.”

Among her many joys she lists the arts, the considerable time she spends in galleries and the couple of events she attends each week.

“I feel very positive about my own ageing,” she says, adding: “We all have a responsibility to keep well and fit”.

In her case that includes regular walks and swims, pilates and yoga. Should she become ill, “I feel very confident in saying that they (her five children) would take care of me,” she says. “I get a lot of instructions from them already: ‘there’s too many steps Mum’, ‘Mum, you’ve got to be careful.’ And it’s true.”

She still works, but to a lesser schedule, attending her city office two or three days a week and remaining deeply involved with a range of organisations.

“There’s so many things I enjoy about being 81. I have some wonderful times. People assume you have more time. People say to me, ‘what are you doing in your retirement?’ and I say ‘what’s that?’ A lot of my friends say ‘how are we so busy?’”

With a still full and carefully delineated schedule, there is one time that Dame Quentin regards as sacrosanct. Listed in her diary as “family commitments”, on this weekly afternoon she accepts no work, nor invitations. Instead she sets out for a local primary school where her youngest grandchild invariably greets her, at the end of the school day, with a delighted smile.

From there the seven-year-old and her grandmother stroll to the shops, sampling lip balms at the chemist, greeting the other shopkeepers, before heading (with a few sweets in hand) to a park bench for “talking time”.

Somewhere, between their cheery renditions of the Sesame Street song, People in Your Neighbourhood, and the reasonably frequent interruptions of passers-by saying hello, the former governor-general of Australia reminds her youngest granddaughter of her luck at living in such a friendly part of the world.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout