Dementia is the leading cause of death for Australian women. How can you delay its onset?

It’s one of the biggest killers of Australians. But new research suggests the number of cases can potentially be halved. And that’s not the only news.

She seemed, in the words of a researcher who observed her for years, the gold standard for healthy ageing. After almost a half century teaching high school students, here she was at 101, still connected and highly coherent, and reading widely on current affairs.

Born in the 1890s, Sister Mary, from Minnesota’s School Sisters of Notre Dame, was one of 678 elderly nuns who agreed, almost 40 years ago, to be monitored for a long-term study into ageing. Over the years the women underwent a battery of assessments: psychological tests, blood tests, probes of the autobiographical essays they had penned upon joining the order. They also sat for lengthy memory tests, for which, even into her second century, Sister Mary was still scoring highly.

But after she died in 1995 and her brain was autopsied – the nuns having agreed to donate their brains as part of the study – researchers were shocked. Outwardly, Sister Mary had been clear and comprehensive. But her brain was riddled with signs of advanced dementia.

Somehow the degenerative disorder feared by so many had not become apparent through the centenarian’s long life, even though her brain was found to be extremely light, suggesting that many of its cells had died. Nor was she an anomaly. More than 60 of the nuns whose brains were examined showed signs of the dementia disease Alzheimer’s. But almost a third of them, including Sister Mary, displayed none of the usually associated confusion or memory loss, and neither had they suffered from strokes.

In the world of brain health, Sister Mary’s story is a salutary tale about an ailment that is both widespread and misunderstood. “People are scared about dementia,” says Professor Matthew Kiernan, CEO of Neuroscience Research Australia, of the cognitive and functional decline that is the leading cause of death for Australian women, and second only to coronary disease for men – and for which, beyond some rare cases, there is no cure. “People don’t know who’s going to get it.”

Even the receipt of a dementia diagnosis can be traumatic. “Some of the horror stories I’ve been told,” says associate professor Elissa Burton, dementia and ageing domain co-lead at Curtin University’s enAble Institute: “ ‘You have dementia. Go home and get your affairs in order’.”

As the results of Sister Mary’s autopsy suggest, having dementia is not always straightforward. If you throw in another illness, the news is likely to be grim. “One brain disease is bad enough,” said the study’s chief researcher, David Snowdon. “But when you add a second disease to it, you’re in real trouble.” Conversely, however, there are a wide number of risk factors that, if modified, can have a surprisingly positive outcome.

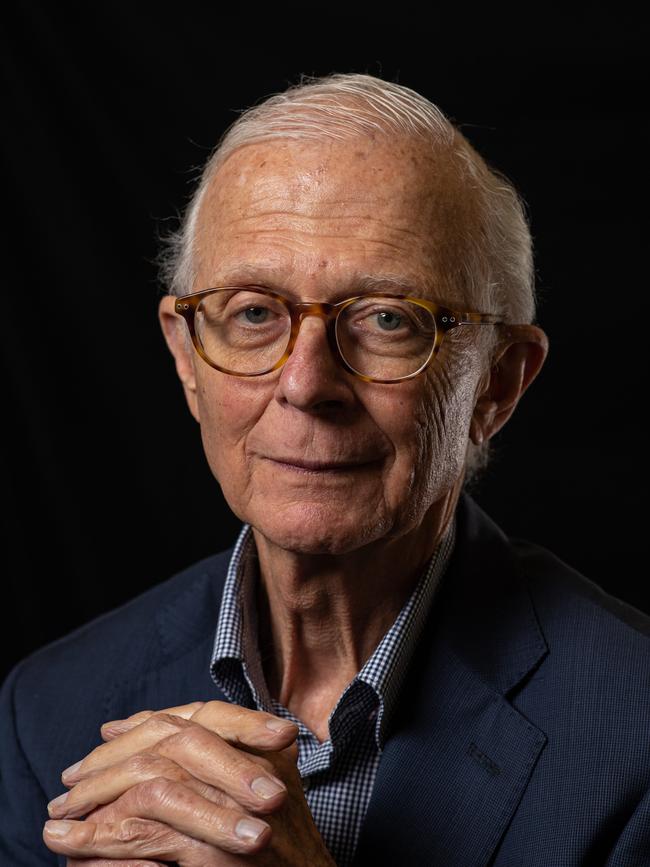

“We can show that by doing certain things we can improve people’s cognition,” says Scientia Professor Henry Brodaty, co-director of the Centre for Healthy Brain Ageing, who is calling for a national strategy for brain health, as widespread and memorable as the 1980s “Slip Slop Slap” awareness campaign for skin cancer. “We can’t prevent dementia but we can delay the onset.”

“There’s an old myth that your brain doesn’t regenerate, that if neurons die they don’t grow back. It’s not true,” says clinical neuropsychologist Anita Goh. The brain does age and change over the years. “But it’s not always negative, and it’s not always a loss of function. It’s just a difference in functioning,” says Associate Professor Goh, principal research fellow at the National Ageing Research Institute. “Younger adults generally may have better physical and cognitive abilities, such as faster processing speed and working memory. But older brains often demonstrate superior strategic thinking, problem-solving abilities, and a broader experience and knowledge base – a bit like a seasoned player’s mastery of a complex game.”

So what happens when something goes wrong as your brain ages? Having a healthy mind is a vital part of ageing well, but it doesn’t all come down to memory. Social health, for example, including the ability to form meaningful relationships, is as important as physical health, says Professor Brodaty: “We know loneliness is equivalent to smoking cigarettes in some (cases).”

People with better social health tend to have less depression and lower mortality rates. But social health can also be seriously eroded with age, as increasing numbers of friends and family die. People who are socially isolated have a significantly higher risk of developing dementia.

Psychological health, such as anxiety and depression, can also deplete with time, thanks to pain or illness. That’s compounded by the fact that older people are less likely to see a psychologist or a psychiatrist. On the flip side, good psychological health is enhanced by having a purpose in life, thanks to, say, religion, or socialising, or having a confidant.

But it’s cognitive health that seems to generate the most concern. And top of the list is dementia, an insidious condition that affects memory, thinking and the ability to perform daily activities. Mainly striking older people, dementia is a series of diseases that impact the brain – Lewy bodies, where clumps of abnormal protein build up, and Alzheimer’s among them – and its ranks are growing. Fifty-seven million people globally are living with dementia today, a number expected to more than double by 2040.

Locally, those figures are equally significant. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, more than 410,000 Australians – or roughly 15 people per 1000 – have dementia. That rate rises with age – to 84 people per 1000 among Australians aged 65 and above. Overall, the number of Australians is expected to more than double by 2058.

But much can be done to reduce that risk of a diagnosis, says Associate Professor Elissa Burton. Even post-diagnosis, there are still actions, such as eating well and exercising, that can enable someone to live well with the disease for a time. “People can live well with dementia for a number of years, especially if they get the diagnosis early,” she says.

Because dementia is not an inevitable consequence of ageing, researchers have been examining ways to stem its impact. In 2017, 24 global experts presented the first report of the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention and Care, identifying nine risk factors, which, over a lifetime, could prevent up to a third of the world’s dementia cases. They included early education, hypertension and obesity in middle age, and diabetes and physical inactivity in late life.

The commission’s most recent report, released in late July, now lists 14 risk factors (see box), with high levels of bad cholesterol and untreated vision loss the two most recent additions. Combined, they can potentially prevent 45 per cent of dementia cases.

The lengthy report carries some good news. “For the first time it is clear that risk can be modified even in people with increased genetic risk of dementia,” say the authors. And with someone, somewhere developing dementia every three seconds, “the potential for prevention is high and, overall, nearly half of dementias could theoretically be prevented by eliminating these 14 risk factors. These findings provide hope”, the authors add.

But there is another layer to this story, and it is not medically based. Dementia is also shrouded in misinformation. The 2024 World Alzheimer Report, released in September, reveals that a massive 80 per cent of the general public believe dementia to be a normal part of ageing. That’s significantly up from 66 per cent five years ago. A staggering 65 per cent of health and care professionals also share that view – which can in turn delay diagnosis and access to treatment.

Not only is dementia not a normal part of ageing, says Associate Professor Goh, but many view it “with fear and stigma”, and consider a diagnosis akin to falling off a cliff.

“It’s something that the media has dramatised, the scary bits of dementia,” she says. “A person with cancer, they don’t typically fall off a cliff the day of diagnosis. They are still working if they can, people don’t treat them differently. But dementia is different. People are off (work) immediately (as if) they have lost all their skills and we have to stop them working.”

Yes, there is a sporadic element to being diagnosed, and even if you follow every medical guideline to reduce your risk, you can still develop it – sometimes because of genetics, sometimes inexplicably.

Prevention remains important. Each year delaying the onset of dementia corresponds to 10 per cent fewer cases being diagnosed. But even after diagnosis, you can potentially slow your rate of decline by heeding other risk factors on that list of 14: tackling bad cholesterol, for example, treating high blood pressure and exercising regularly.

Because dementia involves an inevitable decline, reablement techniques can also help, so that someone who is becoming lost can be taught to use a GPS, or someone with memory loss can be instructed to use a calendar. “It’s about growing new neural connections, still being engaged,” says Associate Professor Goh. “If you get dementia and you completely withdraw from society, that loneliness can make it worse.”

Although there is currently no cure for the vast majority of cases, several medications subsidised through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme in Australia are thought to possibly alleviate some symptoms, and slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in particular.

A new class of drugs offers further hope. Lecanemab, an infusion that has been approved for use in the US, has been shown to slow the rate of memory decline. “The good news is that they are a disease-modifying treatment, so they actually affect the pathology in the brain,” says Professor Brodaty. (In October, the Therapeutic Goods Administration declined to register the medicine in Australia, because its efficacy did not outweigh associated safety risks.)

For Professor Kiernan, the hope is that later generations of infusions will be better. Much like the case of Sister Mary, he is optimistic about future treatments: “You don’t have to die of this condition. You can have it in the background and die of something completely unrelated.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout