‘I thought my partner was hiding something from me. The truth was so much worse’

What do you do when the man you love is diagnosed, at just 46, with dementia? For a long time Louise Bryant thought the answer was silence. But suddenly, that all changed.

Love stories are complex. They can fill you with hope and happiness one moment, and smash you the next. Yesterday you were finessing a future with a family. Today you’re struggling to picture when the person at the epicentre of your dreams last told you he loved you.

They can be tender, fierce, intimate, passionate. But not all love stories have a golden ending.

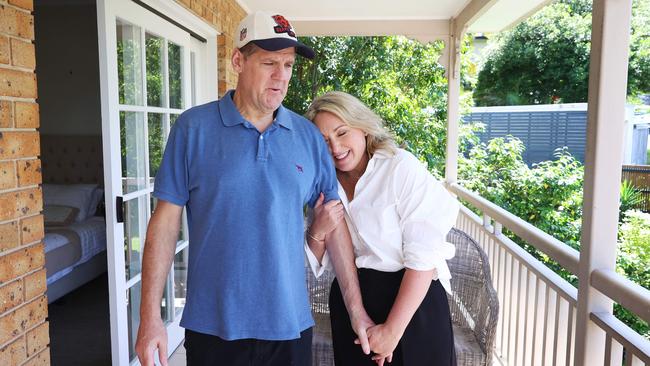

Louise Bryant’s, for example, begins joyously. Then life intervenes, with devastating consequences. Still, along the tricky and unlikely path to where she has arrived, aged 48, with a life partner who has lost his words, and a future in which he will stare at her emptily, she also has learned that you can love without living happily ever after.

Once upon a time she kept this story mostly to herself. “You think it’s going to get better or it’s not as bad as they’re making out, that this is a cruel joke,” she says from the beachside apartment that used to be theirs and where, after years of reluctance, she now lives alone.

But it wasn’t just denial that ensured comparatively few knew that her adored partner, Craig “Moose” Moore, had early onset dementia – and that from age 39 Bryant, his primary carer, was living almost a double life as then managing editor of The Australian, where few knew of the loving turmoil to which she would return from work. “There was,” she concedes now, “a bit of shame attached.”

In Moose she had found a partner brimming with energy, a charming larrikin who had worked in Europe and had swum around the island of Alcatraz, a wordsmith who delighted in composing witty letters to newspaper editors. How would she tell the world this same man, in his early 50s, no longer always knew her?

Their story began a decade ago in Sydney’s heart. A volunteer lifesaver at Bondi Beach, Bryant was at end-of-season drinks at the local Icebergs club in 2013 when a garrulous, middle-aged man approached her group.

An advertising copywriter who lived locally, Moose was an ocean swimmer and a newly appointed board member of Icebergs. “He just arrived at our table,” Bryant says now with a smile. “He seemed to be a friend to everybody; his personality is just out there.”

They chatted and swapped numbers, and he insisted they should have dinner soon. “The first time he bought me pizza. The second time he took me to Rockpool,” she says of the up-market Sydney restaurant. “And that’s when he told me we were going to get married. There was no hesitation. It was just full-on. We fell in love.”

She didn’t answer his proposal but she liked the idea of spending her life with him.

“He loved me and I just felt that he was so genuine in his intention,” she says. “From the day we met we just laughed. It was always a lot of fun and lots of joy and happiness and I felt very supported.”

Moose was a clown, charming, curious, and had a love for pub trivia quizzes. “He was not somebody that I’d met before.”

The father of a young adult daughter, he had a marriage behind him, and within half a year he and Bryant were living together.

Life was sweet, but not entirely. “Beside all this lovely romantic life that we were leading, there were moments where things were somewhat troubling to me.”

Early signs of dementia

In his early 40s, Moose was becoming increasingly erratic, missing appointments, making arrangements “and he just wouldn’t turn up. I would come home and he would be asleep on the couch.”

He started stuttering, a development that left him so embarrassed that he would stop mid-sentence, losing the thread of his conversation, “and he would just walk off, and people would say, ‘That’s a bit rude’.”

Friends became irritated by his sudden unreliability. But when Bryant questioned him, he would remonstrate: “ ‘I don’t know what you mean. I’m sorry, but I don’t know what you’re talking about.’ It just felt like the worst form of gaslighting.”

When he failed to emerge from the water after an ocean race, her concerns that he might be having an affair were overtaken by fears that he had drowned. Eventually she found him wandering the beach.

“He hadn’t been in the water and he said, ‘My goggles broke.’ That’s like saying the dog ate my homework. It’s the worst excuse in ocean swimming.”

Instead of finding another pair of goggles he had simply skipped a race that ordinarily he would have loved. “It really troubled me because it felt like some sort of deception. Some of our friends overheard us and one of them turned around and said, ‘Oh you’re so full of shit Moose’. ”

Whether Moose was overly confident or genuinely confused was unclear as their laughter-filled life became grimmer.

“You’re thinking he is potentially hiding something from me and I can’t put my finger on it but I don’t like it,” says Bryant. “But then in the next breath he would be the most wonderful, supportive, kind partner … I knew that he genuinely loved me but I just couldn’t understand why he was behaving in this way.”

That answer came in 2015. At 46, he was diagnosed with early onset dementia. Around this time, he was in hospital recovering from surgery and his confabulations increased.

“A lot of friends were visiting and he started telling them that we were having a baby, Melanie Moore, and he looked so happy,” Bryant says, crying. “And then I had to run down the corridors and tell them that Moose was not having a baby.”

‘When you care for somebody it becomes quite a privilege because they are so vulnerable. It wasn’t a question that I wouldn’t look after him’ - Louise Bryant on the challenge of looking after Moose as his condition deteriorated

With a diagnosis of persisting cognitive impairment with early onset dementia, Moose returned to their Bondi home, stopped drinking and became a keen walker.

“He would sit here and watch the sunset and say: ‘Oh it’s so beautiful’, and I am thinking in the back of my mind this is not going to last forever,” Bryant says.

With his language failing, Moose had enough self-awareness to realise he could no longer work – and to feel awkward about that realisation. At first he asked Bryant for help with writing, as he lost an increasing number of words, and the skill that had buoyed him through life, and across countries, diminished.

On medical advice in late 2015 he ended his long career as a copywriter. He told those who asked that he had retired.

He assumed many house duties, shopping and cooking, and often joked that he was Mr Doubtfire, in homage to the 1993 film where Robin Williams played an out-of-work actor posing as a Scottish housekeeper. “It was really lovely coming home because he would run to the door and say: ‘I love you, you’re beautiful.’ ”

He spent time at the local shopping centre reading newspapers and meeting friends at the club where he had met Bryant only a few years earlier.

“It was a new normal,” she says. “It wasn’t perfect, but we were happy and he still had capacity to have some of his own independence. We would often say to each other, ‘We are so lucky. This is not a great experience but we are so fortunate to have support around us and we have or have had careers. If we need advice we know who to ask.’ We were able to access the best medical care.”

The Covid lockdowns of 2020 and 2021 meant they were together almost constantly. “It was lovely to have that time together. But that’s when some behavioural changes came into play.”

With beaches closed, Moose could no longer swim in the sea. “And by the time we emerged (from lockdowns) he was terrified of the water.” His pace slowed on their morning walks. He panicked if Bryant was not nearby. He crossed roads without looking. He wandered from their unit at night.

He developed excessive thirst. “He would literally drink anything,” says Bryant. His condition became so dire that she even had to hide bottles of ketchup and vinegar. Eventually he drank close to 12 litres of fluid in one day, so seriously diluting the sodium levels in his body that he collapsed.

But it was not until 2022 that Bryant was able to fathom what might have caused Moose to develop dementia so early. That year, she sought the advice of neurologist Rowena Mobbs, a specialist in assessing potential cases of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. A brain disorder caused by repeated head injuries, CTE can be diagnosed definitively only post-mortem.

In her Sydney office that day, Mobbs was confident that Moose, who had played American football for a time in his youth, did not have CTE. Instead, from his fleeting memory, his made-up stories, his difficulty performing many tasks, his loss of cognition, his brain scans and years of heavy drinking, she diagnosed alcohol-related dementia. Bryant was staggered: “I didn’t know alcohol could cause dementia.”

The man who loved life hardly wanted to step outside any more. He had lost most of his language and needed tending almost constantly.

With the help of carers – at first one person one afternoon, and eventually several people across six days – he was able to stay home in Bondi, even as remaining there became increasingly challenging for those who cared for him.

“It was quite an exhausting, physically demanding time,” says Bryant, who in desperation started to barricade their front door at night in case Moose started to wander outside in the dark. She also was helping him shower and shave. “But when you care for somebody it becomes quite a privilege because they are so vulnerable. It wasn’t a question that I wouldn’t look after him.”

But she was doing so in an increasingly small world. They still joined family gatherings and went to the nearby RSL club, which was safe and familiar. But they could no longer dine at up-market, unknown restaurants and they received comparatively few visitors.

“When you’ve got a brain injury there’s a stigma attached to it. How do you talk to your mate who doesn’t remember your name? How do you talk to your mate who can’t string a sentence together? I don’t blame people who, occasionally you would walk down the street and people would cross the street to avoid talking to you.”

She understands their misgivings. “I saw the looks on people’s faces when they would come up. ‘G’day, Moose.’ Really well meaning. And he was just blank. And yet two months ago they were best mates.”

Rapid deterioration

A year ago, Bryant took Moose back to his neurologist, Mobbs. Six foot and boisterous, he had become agitated and anxious and often scared. Unable to recognise himself any more, if he spied himself in a mirror he’d growl “f..k off”. In the unfamiliar doctor’s room, Moose was pacing, sometimes punching one fist into his palm. Within three minutes, “Rowena said she felt unsafe,” recalls Bryant. “She said, ‘I think it’s time you considered the next stage.’ ” Then, so that Moose would not understand, “she wrote on a piece of paper: ‘nursing home’.”

Bryant was shocked but relieved. “You’ve made the call,” she remembers thinking. “I didn’t have to make that decision.”

In February, she drove Moose to the other side of Sydney, to a quiet suburban street and up to the driveway of a two-storey group home where he would now live.

“It was the worst day I would say of my life,” she says, crying freely, “because it felt like a complete act of betrayal. I couldn’t say: ‘I’m sending you away.’ I had to lie and say: ‘We’re going to see your friend Rocky today.’ I packed a small bag so he would think it’s temporary. I packed his favourite caps and T-shirts.”

As she drove away hours later, the front passenger seat empty, Moose sat down to his first lunch in his new home, where staff served sausages and mash – his favourite meal. Later that day, they sent Bryant the first of many photos. In the company of carers, Moose spent the first afternoon of the rest of his life high-fiving his new neighbours.

He called out “where’s Lou?” 100 times a day in those first weeks. But his language and memory continued to deplete and eventually he stopped asking.

Although it was becoming increasingly one-sided, Bryant kept their relationship alive, making the long trek from her home three times a week to the home that was now familiar to Moose but, like everything else that was once known to him, would not be forever.

There she sat beside him and held his hand, told him she loved him, drove him to the nearby shops that were now his local but not hers, then drove back to the rest of her life – the perception of which finally changed one weekday in September.

On this morning, as usual, his devoted carers sent Bryant a sunny update on Moose’s day. In the video, he was standing at a bench, wearing a favourite cap, and writing what seemed to be the start of a list on a long sheet of paper.

But, like Bryant’s life up to that moment, all was not what it seemed. Moose was wearing two caps and his sweatshirt was back to front and inside out. He was struggling to write and he was making sounds but not words.

“It was the complete opposite of all the photos of joy and happiness and love. It was shattering,” Bryant recalls as she opened the video that had been sent with love.

“It was a bit of a watershed moment because for all this time I had kept everything private, and here was this beautiful person who couldn’t even write his name.”

As she wrote later on a LinkedIn post of her decision to talk openly about their lives: “Awareness and starting a conversation are better than staying silent.” Or as she also says now: “This is what dementia does to people.”

Moose still loves people and dancing, music, talking and cooking, but these days he also loves a McDonald’s Oreo McFlurry, pocketing cardboard coasters, carrying baskets of laundry at his group home, and the stuffed animal dressed in a Wallabies jersey that also resides there.

The wordsmith who can no longer make words is the ocean swimmer scared of the ocean. He gives high-fives generously, especially to people wearing cool caps or T-shirts, but now if he’s frustrated he clicks his fingers. He can no longer read but loves the feel of books, running his finger along the spine or opening the cover and then snapping it shut.

At 56, he is the youngest and most robust resident in his group home. But his future is as anchored here, in this bright, refurbished former family residence with its comfortable lounges and sunny kitchen, as any other resident requiring 24-hour care, even as he still looks like an extra from Bondi Rescue.

Today he is wearing a 2023 Bondi Icebergs Volunteer’s hoodie, floral board shorts and thongs and a Chicago Bears cap. The same man who would dive into the surf, lap the promenade, share a beer and a laugh at the local club, still tosses his cap in the air impishly, but now he does so wordlessly.

One minute he’s joking around, pulling the brim of his cap over his face and darting his eyes from side to side comedically. The next minute, an around-the-clock carer is gently encouraging him to eat a small wedge of orange.

Sometimes his intent is still obvious, even with minimal language: this morning, despite Bryant trying to distract him, he grabs the coffee that a carer has just made for her. “Shi…” he yelps, forming as he often does just part of a word, before quickly dropping the hot mug. Even when he’s unclear, Bryant nods along encouragingly. She puts her arm around him, fixes his T-shirt, tells him how handsome he looks as she shaves his face pre-photograph.

At one point as he strides past her, he grabs one of her hands and twirls her around, as he always might have. And then, silently, he walks on, just like that. Love is complex.

Not everything, though, has changed. It may be at the group home where Moose now lives. But several times a week Bryant can still have dinner with the man she loves. She can still hold his hand. And she still smiles readily at the mention of his name.

“I still get butterflies when I go to see him,” she says proudly. Because love also can be dogged.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout