Nothing prepared me for my beloved’s dementia — but there are lessons I will carry forever

Despite all the advice and the experience I’d gained from my career, nothing prepared me for my beloved’s Alzheimer’s. But there were upsides, and life lessons, which I will carry with me forever.

My husband was sitting on the couch watching Gardening Australia – or rather, seeing the images on the screen and trying to understand what the words meant. Our granddaughter and her three stuffed bunnies were beside him. She had her pink earphones in place and was absorbed by the pink covered iPad on her lap. Grandad was frail – disease had felled him, dementia had stolen his mind – but our granddaughter had his hand.

It was school holidays, sleepover time. My granddaughter and her big brother helped Grandad with his dinner, and when it was time we all ushered him to his bedroom, where they cuddled him and tucked him in. In the morning I found the TV on, his overbed table in place, his electric bed in the upright position and the kids squashed in beside him. The teenage grandkids, whenever they could, threw themselves on Grandad and held him as if he was made of titanium. He wasn’t sure who they were (at this stage he wasn’t sure about anything), but he was certain about the love.

His grandkids were – are – thoughtful, kind and loving. No one had to tell them to be those things, it’s just the way they responded.

It’s one upside of the gusts and floods around the dying.

I found many.

Despite all the advice and the experience I’d gained from my career in aged care, nothing had prepared me for my beloved’s Alzheimer’s. For everyone, it’s a respond-as-you-go trip.

I knew I was in a meaningful relationship with Ian the night we discussed which side of the bed we preferred, then swapped. Not long after, he came home from a rare night at the pub and declared that he loved me and would “walk over broken glass” for me.

I said, “But you’d cut your feet”, and he said, “I’d wear shoes.”

I decided I’d marry him.

Back then I had ambitions, a dog and a past. I’d ridden pillion on a motorbike across America, survived the military junta in Buenos Aires and lived through a London winter in a squat. I could change a tyre, was comfortable with a handbrake start on a hill, and cherished my hammer and screwdriver set. I could repair a blown fuse, open most gates, knew north from south and could usually start the lawnmower. My Dad had taught me to shoot a .22, and even though I couldn’t hit anything I could have been convincing against the Argentinian junta. My aunt had labelled me a “spinster” but I was actually a mature age uni student.

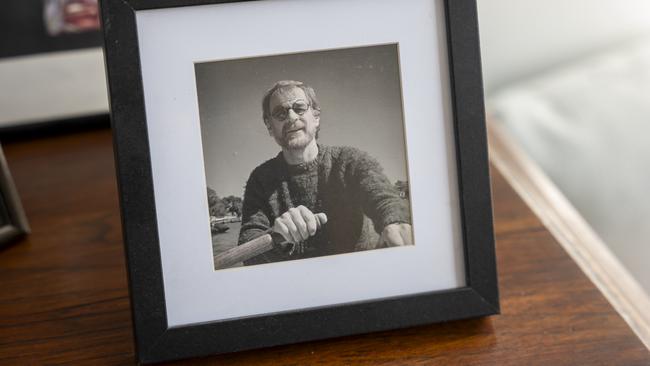

Ian was a single dad, a polymath with an encyclopaedic mind and firm opinions. He started the day with a newspaper, a strong black coffee and the first of many Gitanes, the distinctive French cigarettes. I needed somewhere to live, and Ian needed a tenant. To move my possessions, I packed everything into milk crates that also served as my bed base and drove around the corner to my new room. It took two trips in my VW Beetle. I never used the milk crates again.

Coupledom brought many happy things, though our natural condition was to be autonomous, so at first it was tricky to sort out the sharing thing. We eventually resorted, unconsciously, to loose traditional roles – though Ian still cooked, ironed, used my sewing machine, washed and hung clothes, and I continued to assemble my bookshelves and chop firewood. I relinquished lawnmowing, hanging pictures, freeing immoveable lids and dealing with mechanics. Cars are a bloke thing, I was relegated to navigating (it was before satnavs, so a weekend drive could end in near divorce). I also abandoned general house maintenance and relocating huntsman spiders.

Ian was a builder, a creator; if you asked, he would invent it. He constructed props and sets for stage, film and TV, and built very secret things for magicians. For 30-plus years I lived with creations I didn’t love, but compromise goes with the deal and never more so when we decided to renovate the house. As General Dogsbody my jobs included sanding floors, painting weatherboards, steadying the ladder, holding the other end of the measuring tape and passing tools. Over the years Ian filled his shed with amazing stuff which I declared (dozens of times) he should get rid of it – “You’ll die one day and I’ll have to get rid of it all.”

Routines and habits settled in, mental telepathy developed and we became each other’s barometer. Happily handcuffed together, we maintained our own interests and friends, supported each other’s passions and often travelled without each other.

The kids grew up, got married, had babies. And then things got weird.

Hindsight’s an illuminating thing … but it’s hindsight, so I only vaguely remember the start of the process. My husband lost keys, forgot things, and needed to control everything; he suffered fits of anger, paranoia and defensive behaviour. Honeybunch became a curmudgeon.

Eventually, an Alzheimer’s diagnosis gave us a reason and a kind of dot-point pro forma to follow as we descended slowly into funny-tragic-land. The kids kept one eye on us. Ian continued to lose things, like his car, and when he took the dog to the park and came home without her, the neighbours brought her home, which is when I discovered the neighbourhood community – “Yell out if you need anything.”

When Ian retired, he wandered around the house, bored, irritated and suspicious. Whenever I went away, I had to organise someone to care for him. Gradually, complex communication faltered, and his golfing mates had to guide him around the course. I gave up work to become a carer (a 24-hour job that included helping to measure the ingredients and mix concrete), and though we dismantled the telly to get the CD out together, I alone purchased and mastered the new smart TV.

Sometimes life was hilarious. Ian washed my car meticulously, except for the back passenger side door, and turned his creative drive to the orchard, pruning every tree. His eyes saw perfection; I saw a line of surrealist sculptures. They never bore fruit again. The community rescued Ian when he wandered, the people in the pub phoned when he tried to pay with his library card, and the coffee shop ran a tab for him. He asked me the same question 50 times a day. The more forgetful he became, the more furious I got and the more argumentative and frustrated he was. I forgot that my beloved once invented a prop for a film – a machine that folded a newspaper into a paper aeroplane, lifted it and catapulted it into someone’s front yard – and when I realised my superannuation would go towards a nursing home bond, I hated him.

He would say, “I’m losing my mind” and I would snarl, “Tell me about it.” Those of you who have lived long-term with a dementia sufferer will recognise my behaviour and the regret that goes with it.

It could be said that one of the benefits of Alzheimer’s is sinking into a disease that steals the understanding that you are sinking, that you ever had a past and a future. There seems to be only the given moment, surviving the current circumstance, but who really knows? I once asked Ian who the love of his life was (fully expecting him to name his first wife, since that’s where his memory was stuck at the time) and he said “Catarina Kotsakis”. She turned out to be a woman he’d loved in Greece when he was part of some revolution. I promptly corrected him – I was the best thing that ever happened to him.

On the other hand, no matter how often I asked, he never told me where the girl went when the magician made her disappear, or why her legs still moved after she was sawn in half.

Ian was always pleased to learn that I was his wife – though minute by minute, day by day, we had lost the marriage. Who we really were was extinguished. Disease stole our separate and joint autonomy, our together and separate freedom. We became more handcuffed than ever and, at the same time, almost total strangers.

Technology made being driver and navigator easy, and like Ian I tracked roadworks on major arterial routes and monitored day-to-day petrol prices, checked tyres and topped up the oil … and I appropriated the BBQ. As his childhood meandered through his mind, Ian relived scenes and things fell into place. Feeling safe, I understood, had always been at his core. His pain increased and his mobility declined – blocked arteries, all those Gitanes – and everything was about Ian’s world, real or not, but I was not alone. His best mate found a wheelchair, the kids upped their input, and implements like the electric bed and lift chair (which the grandkids loved) started arriving. Food was delivered to my door, financial matters were sorted and legal requirements completed, and I did absolutely everything for my ailing husband and myself; I perfected his signature and voted for him, got distracted, lost things, got angry and frustrated because I was no longer who I had been ... but it was temporary and life worked better for everyone.

Then one morning I wheeled my husband to the bathroom and found something sinister in our weird, shared realm – but knowing Ian inside and out, I had a hunch. I knew for certain as I watched the doctor at the colonoscopy clinic sombrely approach.

Suddenly, cancer made the timeline almost precise. Again, we united; we consulted oncologists, hard decisions were made and the tender loving care increased. Family holidays were invented; we took turns showering him, checking on him through the night, fetching him drinks. Christmas was super special: memories were created, photos taken, and with all that love my self-pity evaporated. I read the newspaper to our beloved, fed him ice cream, collated photo albums (“Who’s that?” ... “That’s you in New York” ... “I’ve been to New York?”) and enjoyed what he enjoyed – travel shows on telly, clouds, sunset glittering through the perfectly pruned orchard. I taught myself to cut his hair, made sure his toes were right in his shoes and kept him warm. By now I would have happily used my superannuation for anything that would help, though we were happy snuggled in the house that Ian built watching ballet and jazz and symphony orchestras, the telly up to 11, the cancer gnawing away.

He was mine and I was his; family and pain control were the only important things. Extended family and my old nursing friends visited. Any gathering was joyous. Our son introduced surveillance technology so I could check Ian from my own room (and the local pub!) at night. Chatter on the family text stream provided a path to resolving, comprehending, informing, anticipating … and coping. We learned to ask medical people the right questions, made lists, had conference phone calls, enquired, visited, ferried, advocated, nagged, insisted, and chose nice parks to picnic in together. I appreciated our excellent medical system but remained cynical that it seemed to be about technology rather than tender loving care. I became good at assaulting thieving dispensing machines to retrieve my muesli bar, and my survey proved that the cars wrongly parked in disabled spots outside health facilities are always BMWs and Audis. Always.

Centrelink, service providers and aged care facilities deserve their own feature story.

When our beloved went into care, our attentions didn’t wane. Ian became an autumn leaf under his doona, a frail skeletal man with papery skin who smiled and held our hands and adored us, whoever we were. The grandkids prompted him to drink, helped feed him, ate his leftover chips and rode around in his wheelchair. They watched us shower him and lie him gently in bed with his pillows just so; they saw us cry and were intrigued to see some of his teeth go into a dish to soak. “Yuk.” We were grateful for their truth.

Through the bleak sadness, I found death a life-affirming thing. We had tenderly nursed our dearest person through something too awful to truly fathom, and discovered much. For the funeral, the grandkids wrote poems and speeches; our grandson wore the piano keys down to the wood practising a song to play. Our youngest granddaughter studied Grandad’s rather lovely casket, with his golf clubs beside it and his tam-o-shanter cap on top, and asked, “Is Grandad in there?”

“Yes.”

“All of him or just his head?”

Her big brother put his hand around her shoulder and we waited as she came to grips with life and death right there at the wake while a hundred people drank champagne and ate sandwiches and chatted.

Ian’s shed is mine now. I know how to use most tools and yesterday I found everything I required to screw a new bolt to the side gate and a round thing to make the bolt hole. The stud finder allows me to hang my own pictures again and I landed the nail in three strikes of the hammer, as taught by Ian. The new shelves I’ve attached to the laundry wall slope a little, but they do the job. I’ve even changed a door handle. Gaffer tape is my friend and the three ladders I’ve inherited, all different sizes, are suitable for household maintenance like gluing the downpipe back together. Emergency departments don’t bamboozle me, I could sit in a Centrelink waiting room for days if required and I have grown fond of huntsman spiders.

I’ve emerged restored and better equipped.

We all still cry for Ian, and 40 years of photos tell me that I didn’t fully appreciate “us” at the time, but I wonder if we’re capable of that given the immensity of the inevitability of death. I’m more astute at family and at life. Statues of angels, new babies, seedlings or profound stories have more meaning now, and when I encounter an angry person at traffic lights or a rude shop assistant, I include Ian’s point of view, which elevates the spectacle as if he was beside me. In his absence I feel his presence, which at times makes life sharply significant.

I regret that I wasn’t as attentive to my parents as I could have been, but I take solace that they probably felt the same way about their parents and knew I might feel the same. Ironically, wisdom accelerates as one ages into the rear seat in the vehicle of life.

In time, I’ll be decrepit, but the kids know what to do. I’m looking forward to spending more time with them.

My most recent novel, Molly, is a prequel toThe Dressmaker and its sequel, The Dressmaker’s Secret. I wrote Molly during the Covid lockdowns when Ian was so very unwell. The chaos and battles in our life had ceased, and the routine, so important to the suffering, was established, so in the quiet afternoon with Ian settled I ascended to my mezzanine to try and type – such a comforting activity – and out came the story of Molly Dunnage. I wrote of what life had given her and how she detested it but was helpless against it, and I wrote of her strange, passionate aunt who’d made do with what had been taken from her. And, of course, I wrote tenderly of Molly’s failing father. All the while I had one eye on Ian below in his spot with flowers all around him, jazz in his ears and the dog beside him. Molly was the only thing I could write. It was Ian’s last gift to me.

Molly by Rosalie Ham (Picador Australia) is out on October 29.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout