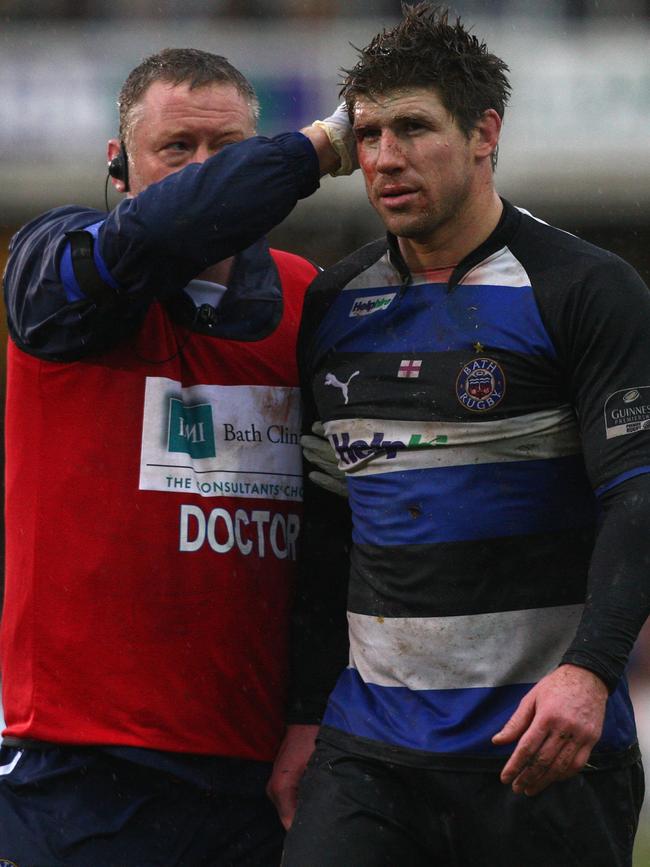

Rugby star Michael Lipman: ‘My head was like a scrambled egg’

In his rugby career Michael Lipman took head knocks in his stride. Now, aged 42 and suffering dementia, he’s paying a terrible price.

The past is a changing patchwork in Michael Lipman’s prematurely failing mind. There is love and sometimes laughter in the swirling fragments of memories and sensations, but what he too often experiences is a combination of loss, confusion and frustration.

At 42, he can no longer remember his last game of rugby, his vocation for more than half his life, although he can still talk about some of the many times he was hit in the head, even knocked unconscious. While he is still raising a young family, he regularly forgets names and confuses faces, and on this sunny weekday as his wife Frankie recounts a recent event, he nods automatically even though he can no longer remember it.

His vocabulary often falters, but Lipman can still convey the anxiety he endures daily because of early onset dementia and probable chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a progressive brain condition associated with repeated blows to the head that can only be confirmed by a post-mortem. He is aware of his fraying filter and mortified at the words that sometimes find their way from his mouth; not so long ago he was banned from a favourite family pub after falling into an instant fury and calling an employee “a f..king moll”.

More than anything on this quiet morning he is distressed at another legacy of his traumatic brain injury: his loss of perspective, which causes him to overreact to mundane events. “You just don’t feel right,” he says of the spaced-out sensation to which he has never quite become accustomed. “For me to be able to describe it is extremely difficult. Because I would love to be specific with you… but literally you can’t, because you’re not thinking straight.”

With Frankie by his side, Lipman, who played professional rugby union in the UK and Australia, and won 10 England caps, is sitting on his living room couch wearing jeans and a T-shirt, his broad shoulders hinting at his past, a pervasive sense of dread hinting at his present and his future. “You’re undecided constantly,” he says, “and you second guess. You take a lot more caution doing anything, even putting coffees in the microwave.”

Coffee has been on his mind this morning, as it turns out. He suddenly reveals he was on his way to a medical appointment a few hours before this interview and bought two espressos, one each for him and his doctor. When his phone rang, he forgot he was carrying the two cups and one spilt over him as he passed a nearby pharmacy. As he recounts this story his speech speeds up and his face fills with anxiety so that his revelation of a non-event feels like a confession. “I ran inside to the chemist and I said, ‘I am so sorry, have you got a mop, have you got towels?’ And they said, ‘We’ll get [the cafe] to clean up.’ And I said, ‘No, it’s my mess’. And they said, ‘No, it’s all right, relax.’” He is visibly uptight by now, hunched and anxious, as he describes walking into the surgery with only one cup, coffee all over his clothes, embarrassed and agitated. “And I am walking in and the doctor said, ‘Calm down, it’s only coffee.’ And I am trying to. But it’s still in my head.”

This is a man who spent a sizeable part of his adult life captaining team mates to multiple victories, who sometimes socialised with royalty, who should be working towards the pinnacle of a long and successful life. His anguished response to an incident that, in another time, would have barely been worth recalling is one of the many consequences of his deteriorating mind.

“I was sitting there thinking, ‘These guys must think I’m an absolute mental case’,” he says. “I’ve made a situation out of a non-situation. But you just can’t relax. You just can’t control it.” Which is why he is still ruminating hours later, as he will throughout the interview, rueing his actions and his reactions, aware that even though thinking is hard, he will likely think about this so much that it will ruin his day. “I am speaking to you,” he says finally, “but I’m thinking about the coffee. It’s little things like that. They’re not important. But they’re important to me for some reason.”

Being Michael Lipman is exhausting. The confusion and the indecision. The misunderstood directions, lost words and heightened emotions. The disconnect between his brain and his bladder that sees him dashing to the bathroom every few minutes. The daily fear of meeting people in case he says the wrong thing or simply because he can no longer navigate small talk, “and I call them the wrong name and then I’m like, ‘I’m so sorry, I’m so sorry’ and then I just walk away while they’re going to walk around going, ‘What a dickhead’.”

Today he brims with self-doubt, but for the first part of his life he was bold, smiling, fast-talking and energetic, “the most gregarious, larger-than-life person I have ever known; he blows into your life like a hurricane”, says his devoted wife. Born in England, he moved to Sydney aged four. At his sports-mad high school, St Joseph’s College, he discovered rugby union. “What got me hooked was how much everyone loved it and everyone loved being part of a team.” A solid and fearless flanker, he became accustomed to burly blokes piling on top of him. “That was one of the traits that I’ve always had, that I was never scared of it or anyone. Which was one of the reasons I was knocked out a lot, because I was never afraid. My dad used to say to me, ‘I love it when you tackle’, and that sort of became imprinted on me.”

He felt dazed or dizzy after many games. But he persevered, partly because he was desperate to remain on the field, and eventually, by Year 12, he was made captain in an environment in which rugby players were venerated. Referees and coaches seemed oblivious to minor head trauma back then. “If you got a knock, they might ask if you were OK, and, of course, you always were.” At his mother’s request he played with headgear, but this added to his sense of invincibility. “You already have this ‘I am indestructible’ mentality. Put some padding on your head and that’s even more so.” Unaware that the headgear probably only protected him from superficial cuts, he felt more emboldened to lead with his head.

The knocks that ensued were an accepted part of the game, he says, and the rattling inside his skull was overlooked as his blossoming passion became his career. After school he played for Sydney club Warringah for two years. At 21 he moved to the UK and joined the Bristol Shoguns, loving the camaraderie. “In the dressing room we used to show each other all our scars… it was war wounds that you shared.” But it was his invisible head injuries that were mounting. During his two years in Bristol, in a home match for which his failing memory now has to rely upon video footage, he was again knocked out cold. When he came to, he tried to chase the ball on his knees, collapsed, tried to run and collapsed again. At a subsequent video review session, the footage reduced his team mates to laughter.

Even then he did not want to leave the field, “even though it was obvious to everyone that I was cooked… but this was rugby, and we were tough men”. Thanks to his perceived courage and resilience, he was allowed to play the following week, a reward that overshadowed any notions he might have had about protecting his health.

As a top athlete, he often thought about his physical frame, but not his head, not even when he was carried off the field five times in one year with his next English club, Bath. “I was just thinking about when I could play my next game.” In his 20-odd years playing the game he still loves, he was knocked out more than 30 times.

He has forgotten what it was like to play his first Test in 2004, called up to the England squad touring New Zealand and Australia and assuming a significant public profile in the UK. At the pinnacle of his career there was a sinister rhythm to his mounting injuries: badly hit at the start of one season by an accidental head clash, he was taken off not because he was concussed but because a swollen eye meant he couldn’t see. Playing against the All Blacks at Twickenham, he was hit in the head in the first 10 minutes and a fuzzy horizontal lined filled his sight “like what you would see on an old malfunctioning TV set”. Worried that his coach might lose respect for him if he asked to leave the field, he played on for almost an hour.

At that time, concussion seemed to be treated much less seriously than obvious physical injuries. After rousing from unconsciousness, he would lie on his back on a field, opening his eyes, an official hovering over him. “They ask you three things. What day is it? Who are we playing? What’s the score? And if you can answer those three questions, carry on.” Sometimes he just pivoted his head towards the scoreboard for the last two answers.

When a doctor in Sydney heard of Lipman’s repeated concussions, he recommended to his mother that he retire from all contact sport. But Lipman loved the game, he had no other qualifications, no other way to earn a living, and no one in England was recommending that he undergo a brain scan. So he kept playing.

Banned for nine months after failing to take a drug test, he resigned from Bath in 2009. (He says now that he’d taken a small amount of cocaine at an end-of-season celebration and that the club tried to test him under false pretences and in a non-approved way.) He returned to Australia, played for the Warringah Rats and signed a two-year deal with the Melbourne Rebels.

In his final stretch with Bath he suffered more head knocks and after many years the medical implications seemed to be worsening. Far from picking himself up each time he was felled, by the time he was playing with the Rebels even relatively light blows caused ongoing headaches, dizziness and disorientation. By 2012, after nine months spent recovering from yet another concussion, his memory and perception were patchy. Reluctantly, he retired from rugby. “My head,” he says, “was like a scrambled egg.”

Like many players, he had no plan for his next chapter. Through acquaintances he fell into a job in real estate. Gregarious and naturally social, on paper he seemed suited to his new career. But he struggled mentally. During speeches about his sporting career, he could not remember what it was like to have played at Twickenham or even for the Melbourne Rebels, his last club. After drinking on his 36th birthday in January 2016 he experienced prolonged amnesia, losing his memory for 16 hours.

Later that year he met his future wife through a mutual friend at a rugby league match. Unaware that concussion was linked to neurodegenerative brain disease, Frankie assumed he had always had a poor memory and that his occasionally odd behaviour and lack of filter were due to a quirky personality. It was not until late the following year that she suspected something was wrong. Lipman – who had been suffering crippling headaches and insomnia – had left her at a lunch and she found him at home hours later, confused and abusive. The following morning, Frankie found out she was pregnant with their son Joey.

Meanwhile, Lipman’s symptoms continued to deteriorate. Concentrating became difficult and he struggled to communicate effectively with clients. He started losing listings and, with less work to do, would return home early. As his income evaporated the couple, with Frankie’s young daughter Summer, moved north from Sydney to the Central Coast, where life was more affordable and a former rugby international player could work in a field that didn’t rely on his memory.

At 39 he became a labourer, but even in this new line of work he could not hide his increasingly worrying traits. He became erratic, cranky and irritable, and sometimes manic, disoriented and argumentative. MRI scans showed no signs of cancer or stroke yet he lost spatial awareness and drove into a telegraph pole one day, and into a tree on another. He became disoriented going to the bathroom at night. Once he drove for 40 minutes to collect Frankie from a friend’s place at midnight, forgetting he had left baby Joey sleeping alone at home.

In 2020, aged 40, and with no history of the disease in his family, he was diagnosed with early onset dementia and with probable CTE. “There was a name for it,” says Frankie. “For Michael, it didn’t give him any sense of relief. But for me, I went from thinking, ‘Who the hell have I married?’ to thinking, ‘You poor thing, you’ve had no control and there’s a reason for these things happening’.”

Others, however, were not so empathetic. After his diagnosis and his history of head injuries was publicised, a group of acquaintances accused him of ruining rugby. “You’re taking the sport we love and turning it into a soft sport,” they told him. “It has got nothing to do with that,” he replied. “I am just hoping to make it safer.”

It was once known as punch-drunk syndrome. First detected in boxers nearly a century ago, and more recently in American footballers and UK soccer players, CTE is a slow, inexorable type of dementia caused by repeated head injuries. Those knocks lead to abnormal proteins building up and spreading within the brain, impairing connections and neurons and ultimately eroding the brain itself. Its most common symptoms include memory loss, confusion, mood changes and erratic behaviour. Although often associated with athletes, it can also impact victims of explosions, frequent falls and violent and repeated assaults.

“CTE steals a player’s independence in retirement and their time with family,” says Lipman’s neurologist, Dr Rowena Mobbs. “This is a devastating condition.” Mobbs is also director of the Australian CTE Biobank, which collects samples and clinical data from people with possible or probable CTE. Many of her 170 patients, most of them athletes, have each endured more than 100 concussions. While Lipman’s probable CTE diagnosis can only be confirmed after he dies, “as a clinician I am confident he has it”, says Mobbs, listing his symptoms including memory loss, irritability, anger, and impaired insight.

Because it can only be detected in an autopsy, the rate of CTE is unknown in Australia. It has, however, been confirmed in the post-mortems of multiple high-profile footballers including the AFL’s Polly Farmer, Shane Tuck and Danny Frawley, and NRL champion Steve Folkes. Over the past three years, more than 20 brains have been donated to the Australian Sports Brain Bank for research, all of them from athletes who played in sports with risks of repetitive head injury. More than half were found to have had CTE.

Studies in the US suggest CTE has struck anywhere from 15 to almost 90 per cent of NFL players. But even its link to injuries among athletes has been open to conjecture. In a government-funded position statement on concussion in sport, released in 2019, bodies including the Australian Institute of Sport and the Australian Medical Association maintained there was no reliable evidence clearly linking sport-related concussions with CTE. Yet a report published last month in the clinical journal Frontiers in Neurology, authored by researchers in six countries, claims there is in fact “convincing evidence” that repeated head impacts cause CTE.

In response to growing alarm about the cumulative effects of head injuries, Australian sporting codes including the AFL, NRL and Rugby Union have all introduced concussion protocols governing, among other things, medical clearances and the duration before a player can return to the field post-concussion. Because of his condition, Lipman is now part of a huge UK-based class action involving nearly 200 players against multiple rugby union organisations, including World Rugby, challenging their responses to player safety and brain health during games and training. Dozens of former amateur rugby union players have also begun legal action.

The impact of years of hard knocks lingers. For his young household, Lipman’s health presents continued challenges. “Michael’s diagnosis has taken over us,” says Frankie, who, depending on the day, can feel like either her husband’s partner or his carer as his wellbeing touches almost every aspect of the family’s life.

Now running a business in the Hunter Valley as her family’s main earner, last year Frankie, at 40, unexpectedly fell pregnant twice. Both times she miscarried. “We love kids, and we would ultimately love a huge family,” she says of the mounting costs her family is facing. “Something that should have been the biggest joy, we actually had to question whether we would actually bring another child into the world.”

Not everything has changed because of his diagnosis. Frankie still thinks of her husband of five years as larger than life. But now he’s the stay-at-home dad hoping for some work as a public speaker, forever wondering about his new place in the world, anguish invariably hovering. “I’ll go to my son’s birthday parties and be just like a closed book. There’s times where I’ll probably embarrass myself in those situations so hence I avoid them.

“I live through Frankie on a daily basis. Every day I say, ‘So what have we got on tomorrow?’” Overwhelmed by options, he asks his wife to help him reply to emails and pick his meals from menus. “She saves me every day.” He cannot remember when she told him about this interview.

Frankie and their young children Summer and Joey are the light as he passes through a dark tunnel. “I love our family,” he says, when asked to rate his life. “We sit down at dinner – for me that’s my little happy place… We do little dances together. Those sorts of moments, they’re the best… Obviously I’m very happy to have played in front [of huge crowds], but when you get into the real world you can experience unconditional love within your own family. That’s priceless.” And he smiles. In his daily struggle to navigate a life path through confusion and loss, it is a rare moment of joy.

Concussion by Michael Lipman and Frankie Lipman (Allen & Unwin, $32.99) is published on Tuesday.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout