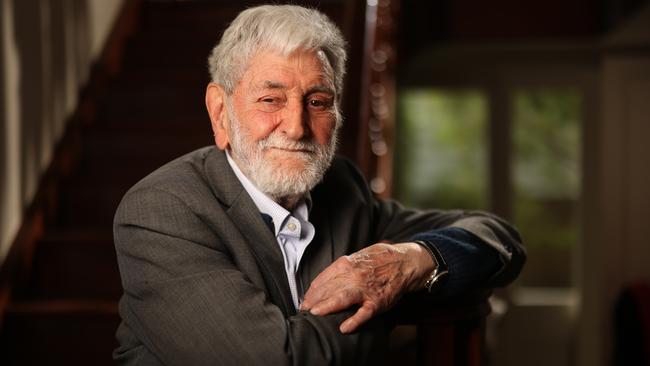

‘I hesitate to say sexy, but I think I look pretty good’: Barry Jones is as sharp as ever at 92

He has one of the biggest brains in the country. So how does Barry Jones approach life at 92?

It might sound like a cricket score, but 92 not out has a special significance for Barry Jones. As a son of pre-war Melbourne, when longevity was measured in considerably smaller blocks, eight years shy of a century was not an age to which he was accustomed. “I’m certainly the longest surviving male in my family history,” the former federal science minister reveals.

And here he is today, just turned 92, and by his own assessment he’s pretty fine

“People say, ‘Oh you’re doing very well, you’re looking very well’ and I think I am looking well,” he says proudly. “I notice when people take pictures of me, I don’t want to kid myself, and I hesitate to say sexy, but I think I look pretty good.”

Over a long lifetime, the wonderkid quiz champion turned lawyer, writer, and National Trust-declared Australian Living Treasure has amassed a packed and ever-expanding CV. In his tenth decade, he continues to write, to think and to explore.

Still, his life today is only so full. “I’ve got certain things I want to do and certain things I recognise I won’t do,” he says. Recently, for example, he was “taken over with enthusiasm to have a look at Egypt one last time”, and might well have been there today. “Everyone I spoke to said, ‘Oh no, no, don’t even contemplate it … There’s just too much climbing, too much of a risk you’ll fall, or too much of a risk something will go wrong.”

So he opted for a solution closer to home and which harvested his vast array of memories and photos. He visited an exhibition on Egyptian treasures in Sydney, and another in Melbourne on British-acquired treasures. Although far from the Middle East, he was happy with these alternatives. “I can see the practicality if I did go there and have a fall. It could be pretty messy.”

Risk mitigation has become an important factor in his later-life. He’s happy these days being at home in Melbourne, with his busy mind and his vast library of personal photographs.

Is he sad that he may not again see vast tracts of the world that he once so loved to visit and to photograph? “There’s regret. There’s no use going boo hoo. There’s certain things you can do and certain things that you can’t,” he says of his age and the limitations he says it brings. “If I were weighing up happiness and unhappiness, I have regrets but not obsessive regrets about things I can’t do readily and I’m a bit paranoid about falling over. But I would give myself eight out of ten for the quality of my life.”He still visits art galleries and attends literary festivals and is heading to Western Australia at the end of the year to hear the Australian Chamber Orchestra. But the rhythm of his life has changed and so has the centre of his world.

“I am housebound in a way I wasn’t before. I’m not complaining. It just means home is comfortable to work from. I’m still writing a lot and thinking things through. … The material I am working on is close at hand. Do I really need to go to the State Library to look for something? Not really.”

Compared to his previous decades, his 90s life “is curtailed in the sense that I am not as mobile as I was”. He can no longer read in his right eye, which has in turn led to concerns about his depth perception, and he has started using a walking stick.

But with his sharp mind, no sign of the dementia that so many fear nor of any manner of chronic illnesses that have befallen too many of his contemporaries, “I know I am ageing well,” he declares proudly, nominating music and being busy as two key factors.

“I concentrate on being good from the head up. I drink very little, I eat well, carefully. I wouldn’t say I was particularly conscientious about exercise.” To age well, he says, “the central thing is keeping your mind active, being endlessly curious, trying to improve the world, thinking globally”.

A life well lived also leads to thoughts of how to celebrate its conclusion. Yes, he says, he contemplates his funeral often. Lately he’s been mulling the specifics of the ideal location.

“I’ve been thinking about what sort of organ I want. I’m deeply interested in religion but I wouldn’t necessarily regard myself as a religious person. But a funeral wouldn’t be a funeral without some Bach, and having some Bach involves having a pretty good organ. So do you want to have an event at some antiseptic, neutral ground or do you want somewhere with an organ where people can walk out to Bach?”

He hasn’t settled on a location yet, because the Bach piece he has in mind is especially long. “The trouble is, will people want to go to a funeral that lasts about four and a half hours? Probably not.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout