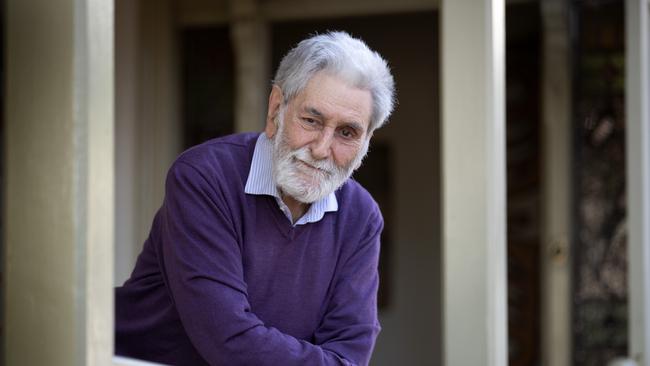

Labor luminary Barry Jones warns of the ‘retreat from reason’

One of Australia’s most well-known and perplexing politicians, Barry Jones’ indictment of our modern political landscape is scathing — and should be a wake up call.

“There is no desire more natural than that of knowledge. We try all ways that can lead us to it; where reason is wanting, we therein employ experience, which is a means much more weak and cheap; but truth is so great a thing that we ought not to disdain any mediation that will guide us to it.’’

Jones’s life has been devoted to the pursuit of knowledge through reason and experience. It is this focus that made him a singularity in politics, as minister for science in Bob Hawke’s government (1983-90) and as national president of the Labor Party (1992-2000; 2005-06). He was popular with voters, who remembered him as a quiz show champion in the 1960s, which gave him a profile and set him apart from others.

In a new book, What Is To Be Done, Jones warns that we face a series of interrelated existential challenges which threaten the advancement of civilisation and the welfare of humanity: climate change, pandemics, terrorism, racism and state violence, and the rise of religious fundamentalism and political populism. That’s just for starters.

A lifetime of reading, study and analysis, coupled with experience, has led Jones to the bleak conclusion that political systems here and overseas are failing to adequately grapple with these challenges. He mostly blames political leaders. But citizens are not absolved of responsibility. We have never been better educated yet our public discourse has never been dumber.

“The two hegemonic political parties (the Coalition and Labor) are oligarchies which are essentially looking inwards,” Jones tells Inquirer. “Their major preoccupation is finding loyal people around them who will put their hand up at the right time and who are not particularly interested in great ideas.

“When I was in parliament, even though many had left school early and did not have formal qualifications, the quality of debate was electrifying. Politicians were passionately interested in ideas; now politicians are passionately interested in not losing the support of their base and winning the next election.”

With compulsory voting and guaranteed public funding for election campaigns, Jones says the major political parties do not really need to engage with the community to get them interested in ideas and to vote. The result is that voters feel disengaged and will vote anyway, while parties have become inward-looking.

He warns that in the US and Europe, and to some extent in Australia, liberal democracy and Enlightenment values are at risk. “We see a retreat from reason; the rejection of facts and expertise; the rise of populism, snarling nationalisms, tribalism, and conspiracy theories; a fundamentalist revival and hostility to science; a failure of ethical leadership; deepening corruption of democratic processes; profound neglect of the climate change imperative; and the triumph of vested interests,” Jones writes.

His new book is a follow-up to his international best-selling examination of the future of work and technology in a post-industrial world, Sleepers, Wake!, published to acclaim in 1982. A legacy of that book is that Australia did embrace economic change, led by Hawke and Paul Keating, supported by voters, with Australian entrepreneurs making the necessary transformation.

“It is possible to change things,” Jones insists. “If we change the political culture, we’ll change the way people react if politicians get out and argue a case. Well, that doesn’t happen any more.

“We are in an era now of political minimalism, with an ultra-cautious and short-term view. There is a failure of nerve, not only by the government but by the opposition as well.”

What Is To Be Done blends an astonishing array of scholarly research with insights from history, philosophy and literature, coupled with biographical reflections and anecdotes, to assemble political and policy recommendations that make a persuasive case for a new way forward.

It includes a damning indictment of Australia’s major political parties. “If you were going to rename the parties, you might rename the Liberal Party as the Self-Interest Party, the National Party, which represents miners more than farmers, could become the Coal Party and the Labor Party could be renamed the Tepid Party,” he says.

Jones lashes Anthony Albanese and Bill Shorten. He says Labor lacks boldness and conviction, the capacity to develop detailed policies, and the ability to argue convincingly and persuade voters; and is plagued by a short-term, reactionary approach to politics. He describes Labor as “undemocratic, structurally moribund (and) heavily factionalised”.

It is unimaginable that Neal Blewett, John Button, John Dawkins, Michael Duffy, Bill Hayden, John Kerin, Susan Ryan or Peter Walsh could win preselection for a safe Labor seat today, or indeed himself, Jones says. It is almost impossible for anyone without union or factional patronage to break into Labor’s parliamentary ranks.

“Typically, the reason people join political parties today is not because they have a passion for an idea, it is because they see it as a career,” Jones says. “I remember saying that if you look at those national conferences, over which I’ve presided, and you saw the serried ranks of well coiffured graduates, you would be more likely to find a platypus than you would a working-class delegate who came off the factory floor.”

Scott Morrison, Malcolm Turnbull and Tony Abbott are not exempted from Jones’s critique. Nor are the Liberal and National parties. “Morrison is essentially a salesman, a Willy Loman,” Jones writes. “In an age of retail politics, the fundamental issue for him is, ‘Will it sell?’ (At the last election) he was essentially selling a single product: short-term self-interest.”

In chapters that address Australia’s political system, Jones explains how a focus on retail politics and the dumbing down of public debate has alienated voters. “Many current MPs simply don’t know how to frame a debate,” Jones says. “They receive a set of dot points, then repeat, repeat, repeat. They simply don’t listen to the alternative argument.”

He places a premium on political leadership and wants citizens to re-engage with politics to force their elected representatives to identify the problems we face and develop policies to address and adapt to them.

“If Labor would find a bit of courage, they might encourage the other mob to be courageous as well and to concentrate not so much on asking how we win the next election but what is the kind of Australia we want? Are we wanting to be an intelligent, thoughtful, understanding, compassionate, embracing kind of society which can be a model for the world? Or do we not need to worry about generating new forms of national income because we have got stuff we can dig up that’s low in added value and just concentrate on that? It’s not enough and it won’t be enough.”

For several decades, from the 1970s to the 2000s, Jones was one of Australia’s most well-known though perplexing politicians. He concedes that some colleagues in the Victorian parliament (1972-77) and the federal parliament (1977-98) found him too “idiosyncratic” and lacking the requisite “killer instinct”. Jones says: “I was more interested in getting the policy settings right than I was in personal advancement.” Hawke and Keating found Jones frustrating and irritating.

He had a torrid time trying to get funding for science initiatives in expenditure review committee meetings. “Hawke was obviously very brilliant, he was a very good chairman of cabinet and he had an amazing capacity to master a brief,” Jones says. “Antarctica is an area where I might have had a bit of influence on him. But I did find it difficult to get his attention on research and development issues.”

However, Labor Party members loved Jones. As national president during the 1993, 1996 and 1998 elections, Jones authorised election advertisements. Focus groups of voters were often unmoved by Keating or Kim Beazley, or Labor’s policies, but always lit up when they heard Jones’s name mentioned: “Authorised by Barry Jones, ALP, Canberra.”

Jones was a contestant on TV game show Pick a Box, hosted by Bob Dyer, in the 1960s. He was known for his long answers and for challenging the premise of questions or the accuracy of answers. He earned $55,000 in cash and prizes over eight years of appearances. This gave Jones, then a high school teacher, a profile which boosted his campaign to end the death penalty and led to him hosting radio programs in Melbourne.

“I still get emails from people who remember that when they were a kid, often growing up in a remote country town without any books in the house, their mother used to say: ‘You’ve got to watch this man on Pick a Box.’ They say they learnt about how to analyse things, how you work things out, how you reach conclusions, how you argue the case. It is very touching when people say that I had an influence on their life. I’m staggered by that.”

While Jones has been a minister, a party official, worked with UNESCO in Paris and advised governments around the world on adapting to technological change, it is his support for the arts that has been especially rewarding. He helped to restart the Australian film industry in the 1960s and 70s.

Today he worries that the escalating cost of humanities degrees will see graduates with skills that may be obsolete within decades while missing out on an education in “the life of the mind”. It is in reading books, listening to music, enjoying the performing arts, exploring history and philosophy, and marvelling at great works of art that can be the most illuminating and fulfilling experiences in life.

Jones turned 88 this month. The secret to living a long and productive life, he suggests, is to remain curious about the world and to never stop trying to understand it and shape it. It also satisfies a need deep within. “I’m curious to understand myself, perhaps in the tradition of Montaigne, as much as anything else.”

Barry Jones’s What Is To Be Done: Political Engagement and Saving the Planet is published by Scribe on Tuesday

At the end of a long interview with Barry Jones — the irrepressible, hugely intelligent, always insightful and utterly unique man of letters with a kaleidoscopic mind — he asks if I have read Michel de Montaigne’s essay Of Experience. I confess that I have not and concede that I probably should. “You must,” he says. “It’s a masterpiece.”