Former Coalition prime minister John Howard understood Australians support a fair go for our Aboriginal population but are not interested in political fights for symbolic rights, especially rights that do not accrue to all Australians.

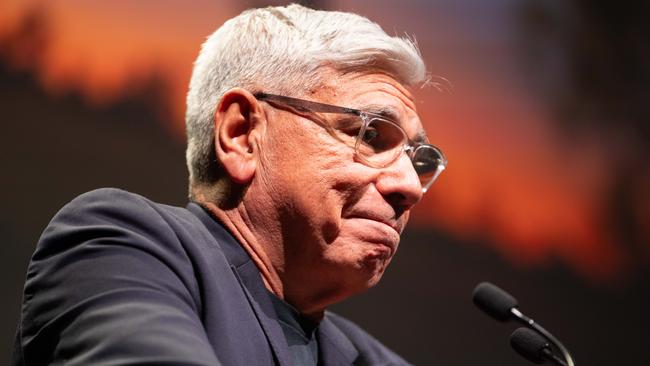

Voice architect Noel Pearson on May 28, 2000, decided against joining the Sydney Harbour Bridge walk of 100,000 people supporting reconciliation. The Cairns Post on Saturday May 27, 2000, reported Pearson the previous day had told a Cairns conference reconciliation had been lost in “religious and spiritual feel-good stuff” and remote Aboriginal Australians did not understand it.

Pearson is now campaigning as the architect of the Aboriginal voice to parliament, which he sees as a way to secure better practical outcomes for remote communities, but which opponents claim is a political power grab by urban Aboriginal rights activists.

Sounding much like Pearson 23 years ago, No case leader Warren Mundine has challenged Yes claims the voice is supported by 80 per cent of Aboriginal people. Mundine has written on LinkedIn that in remote communities, the pro-voice organisation Passing the Message Stick has found 45 per cent of adults have no idea what the voice is about.

Political symbols and practical actions play to sharply different constituencies in the Aboriginal world. For wider Australia and for No case leaders such as opposition Indigenous Australians spokeswoman Jacinta Nampijinpa Price and Mundine, reconciliation and recognition need to bring improvements in living conditions for people in remote Aboriginal communities who have the nation’s lowest life expectancy, highest infant mortality rates and worst school education results.

For many well-educated, urban Aboriginal leaders and academics, constitutional recognition and the push for rights, treaties and perhaps reparations have always been about political and legal power.

Activist academics such as Marcia Langton and Megan Davis sit squarely within an international movement that seeks to win for Indigenous peoples some form of redress for European colonisation. It’s a movement that won’t stop even if the voice referendum fails.

When Price told the National Press Club in Canberra on September 14 that she did not think colonisation had lingering negative effects on Aboriginal Australia, many left-wing journalists seemed shocked. Yet for many remote area Aboriginal people, the Indigenous world can be harsh and the benefits of modern civilisation Price mentioned – running water and plentiful food – are powerful.

Many activists don’t like media reporting that focuses on Aboriginal disadvantage or the harsh ways of the remote world. That’s why they pushed for the Albanese government to remove alcohol restrictions Pearson himself says communities may desperately need. The right to buy booze should not trump the rights of Aboriginal children to a safe environment and healthy food.

This column has previously reported being approached in the early noughties by a delegation from the then peak body, ATSIC (the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission), requesting that as editor-in-chief of Queensland Newspapers I stop sending reporters to Cape York to tell stories of abuse of women and children.

ATSIC recommended a series of stories about young Aboriginal people in Brisbane doing great things in the creative industries.

History records The Age in Melbourne revealed sexual allegations against ATSIC boss Geoff Clark, and Tony Koch in The Courier Mail reported stories of alleged financial malfeasance against Clark’s Queensland deputy “Sugar” Ray Robinson. Eventually, the Howard government in 2005 scrapped ATSIC.

ATSIC’s axing lies at the heart of the present demand for a constitutionally enshrined voice.

Aboriginal activists saw its destruction as a measure of the racism of colonial Australia. Yet in remote communities, some of the most disadvantaged Indigenous clans believed ATSIC’s demise would stop some strong males using their financial clout through ATSIC to intimidate, and profit from, remote family groups.

This sort of intimidation continues today in some communities where some strong patriarchal figures use their roles in prescribed native title bodies corporate to enrich their own families and deny payments to royalty holders found by Native Title Tribunals to be entitled to regular payments from mining ventures.

Like questions of practical reconciliation, there is less difference between Mundine and Pearson on voice and treaty. Many Yes media supporters seemed shocked when Mundine admitted to Insiders host David Speers on September 17 that he remains a supporter of treaties.

This column on July 31 reported former PM and voice critic Tony Abbott had told parliament in 2013 that Aboriginal Australia needed an equivalent of New Zealand’s Treaty of Waitangi. That column quoted Mundine saying, “I believe treaty gives direct power to the grassroots and is more useful than voice”.

This too is similar to what Pearson believed back in 2014, when he thought local voices feeding into regional voices and finally a national voice was the way to go.

And even though he used his powerful speech and question time at the press club last Wednesday to deny the No camp has a point when it says voters need more detail about how a voice might work, he was not so long ago on the same page as Mundine about detail.

Paul Sakkal in The Sydney Morning Herald on September 26 noted, “Between 2018 and 2021 (former Labor leader Bill) Shorten, Pearson, … Langton and former High Court Judge Murray Gleeson each stressed the importance of either creating the voice via legislation first or releasing an exposure draft bill to educate the public.”

Pearson at the press club, questioned about this by Rosie Lewis from this paper, said the parliament under the referendum model would have absolute power to legislate the way the voice works. This is true but will not quell the scare campaign.

Yes case leaders can’t say it, but here they have been let down by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese. They were promised a “recognise” referendum by Labor prime minister Julia Gillard, by Abbott and by Malcolm Turnbull. They looked at a possible legislated voice with the Morrison government after it commissioned the Calma-Langton report.

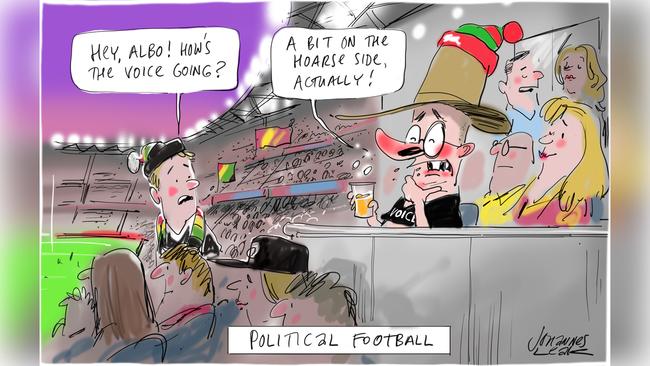

Unsurprisingly, given that history, Yes advocates grabbed the opportunity when Albanese promised a referendum on election night in May last year. Yet as this column said on September 10, “The Yes case … has been more damaged by the Prime Minister than by No case arguments”. That piece went on to argue Albanese should have delayed the referendum until his second term, worked out the detail of the voice and launched a public information campaign.

Opposition Leader Peter Dutton has promised a referendum on recognition and a legislated voice. The gap between his position now and Albanese’s is much slimmer than shrill media opponents of the voice suggest.

The PM should have always known the referendum would need bipartisan support to succeed.

Falling support for the voice proposal suggests Yes activists and media supporters have failed to understand the decades-long balance in Australia between practical and symbolic reconciliation.