You won’t read about what Yes leaders and Labor powerbrokers are saying privately because most journalists support an Aboriginal voice to parliament.

Neither politicians nor the Aboriginal leadership will go on the record but privately many acknowledge Anthony Albanese has undermined his own referendum.

Journalists pushing the Yes case claim the $100m war chest organisers have from corporate Australia will sway undecided voters before the October 14 vote. They talk about 40 per cent of Australians being undecided.

They are wrong. The Newspoll published here last Monday showed only 9 per cent undecided. But a 53 per cent outright majority were opposed and only 38 per cent were in favour. This column wrote right back in January that Yes was already losing momentum.

Feeding into such pessimism is an angry electoral mood. Voters do not want to hear about the voice. Market research has persuaded some private sector advertisers to hold off on campaigns because consumers are so angry about cost of living and a government focus on things they don’t care about, particularly the voice and AUKUS.

Labor researchers have similar data. Labor national secretary Paul Erickson in February told the parliamentary party that voters want to talk and hear about only one thing: the cost of living.

This is an invidious position for Albanese. He is the only political leader with enough profile to advocate for the voice but he drives his own opinion poll ratings down each time he does and may also be damaging the voice.

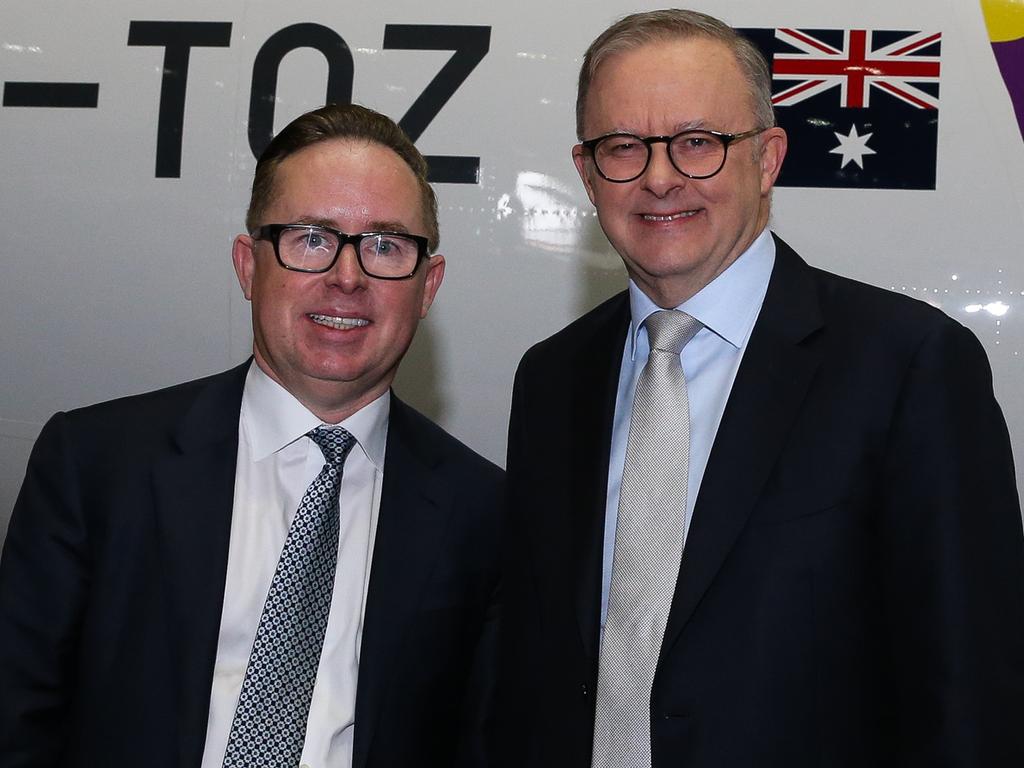

Paul Kelly here on Wednesday nailed a related problem. He asked what had happened to Albanese’s political radar: why was Labor linking so much of the Yes case to Albanese’s relationship with Qantas, a brand that is poison?

Self-evidently, linking Albanese’s signal first term project to elite groups such as big companies and sporting organisations simply feeds into criticism the voice is a concern of the elites.

And as Cape York Aboriginal leader Noel Pearson and other voice activists have realised too late, vilifying voice critics or voters with legitimate doubts as purveyors of misinformation only hurts the Yes cause.

It is not misinformation when voice critics discuss the potential for “truth, treaty and reconciliation” in the wake of a successful referendum. The PM specifically endorsed all three when he committed to the Uluru statement on election night last year.

The second last paragraph of the statement says: “We seek a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between governments and First Nations and truth-telling about our history.”

Nor is misinformation absent from the Yes case. Even the ABC Fact Check on September 1 ruled a Twitter meme about No case leader Warren Mundine having supported the voice in 2017 was a mis-edit of what Mundine had actually said.

The ABC also called out Yes case misinformation about the 1967 Aboriginal referendum which allowed the federal government to make laws for Aboriginal people previously subject to state laws. The ABC said the claim Indigenous people had been counted as flora and fauna before 1967 was incorrect.

Even ABC Media Watch gave some support to Sky News host Peta Credlin’s claim the Uluru statement is more than 439 words, including an “Our Story” historical view. Fair enough, given Credlin quoted Aboriginal academic Megan Davis specifically saying in 2018 that the statement was more than a single page and included the Our Story text.

It’s good to see this attempt at fairness by the ABC. Unlike Sky News, which has allowed differences of opinion on the voice, the national broadcaster has been a one-sided voice barracker. Good on Sky News for standing up for Chris Kenny’s right to disagree with Credlin and Andrew Bolt.

That said, No campaigners were off the blocks early with false claims the voice would be “a kind of Aboriginal only parliament” and that it would be dividing Australians by race. Race is already mentioned twice in the Constitution and the Mabo and Wik decisions gave Aboriginal Australians property rights not available to other Australians 30 years ago.

And of course race is already the great divider of Australian society given indigeneity is a direct predictor of lower life expectancy, higher imprisonment rates, high infant mortality, childhood disease, poor education, and poverty.

Albanese had heard most of the No case arguments before he dismissed good advice from conservative Yes supporters such as Father Frank Brennan and former Coalition spokesman on Aboriginal affairs Julian Leeser.

Brennan did not miss Albanese in a piece here last Saturday outlining the PM’s various voice missteps this year. He concluded: “Regardless of the result, I do hope no future prime minister again makes a series of captain’s picks (about a referendum) without a process for public engagement. That’s no way to bring the country together to Yes.”

As this column pointed out in August 2022, the Calma-Langton report to the Morrison government that Albanese is using as his voice guide contains many recommendations voters will not support.

They support constitutional recognition but would only support a voice that spoke to matters directly affecting Aboriginal people. They are sceptical that members of the national voice are to be appointed rather than elected. Many voters are interested in local voices that might help solve problems of regional Aboriginal life but the referendum proposal is silent on this.

This column has previously argued voters may be sympathetic to a voice that subsumed most other Aboriginal lobby groups and took formal responsibility for Aboriginal spending to try to ensure money goes where it is needed.

Pearson at an address in Sydney last week for The Australian took these issues head on. He admitted too much money had been wasted with little positive result in closing the gap. Aboriginal bodies needed to be accountable and remote communities needed the freedom to apply solutions that work locally, such as alcohol bans.

It is on this kind of welfare reform that Pearson made his reputation in the 90s and noughties and it is here that the so-called soft-No voters he says Yes needs to target may be open for dialogue.

The question Albanese will not want to face, and few urban Aboriginal activists will even contemplate, is whether the only slim path to a Yes vote now lies in harnessing voter anger against politicians who have failed Aboriginal Australia and wasted hundreds of billions of dollars doing so. Albanese could not lead such a strategy.

Said Pearson discussing his decades of work on rights and responsibilities in Cape York: “Until we take responsibility, there’ll be no turnaround in closing the gap.

“You think my mob like it when I talk about responsibility?

“They love it when I talk about rights and how they’ve been victimised. They don’t like it when I say take responsibility for your children – nobody’s going to save you until you get your family together.”

It’s not what Albo’s mates in the ALP Left are used to hearing. But it is what middle Australia thinks, and few Yes Aboriginal leaders can speak that language of personal responsibility.

The Yes case for October’s voice referendum has been more damaged by the Prime Minister than by No case arguments.