Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and much of the Yes campaign pretended Albanese had not promised to implement in full the Uluru Statement from the Heart – on election night last year, at Garma in Arnhem Land last year, and in parliament. The 2017 statement, which Albanese has framed as a generous offer to mainstream Australia, specifically asks for a voice and a Makarrata Commission that can pursue truth and treaty.

The PM was annoyed when pressed by 2GB radio host Ben Fordham on July 19 about the treaty issue, denying there was any link between the voice vote and subsequent processes. Yet the link between any form of recognition in the Constitution and an eventual treaty has been discussed for a decade.

Remember, the Labor states of Queensland, Victoria and South Australia as well as the Northern Territory have already formally committed to treaty processes.

Victoria in 2021 set up the Yoorrook Justice Commission to begin the process of truth-telling.

State-based approaches are historically appropriate given most violence between Aboriginals and early settlers happened before Federation in 1901.

The fact the public largely knows little about all this points to the failings of an education system that for most of our history focused on the kings and queens of England and the white explorers of the 18th and 19th centuries.

It also says much about the failings of the political and media class that negotiations with Aboriginal leadership groups have largely been conducted behind closed doors with little reporting and almost no attempt by leaders of both sides of politics to build a consensus for constitutional action both sides supported.

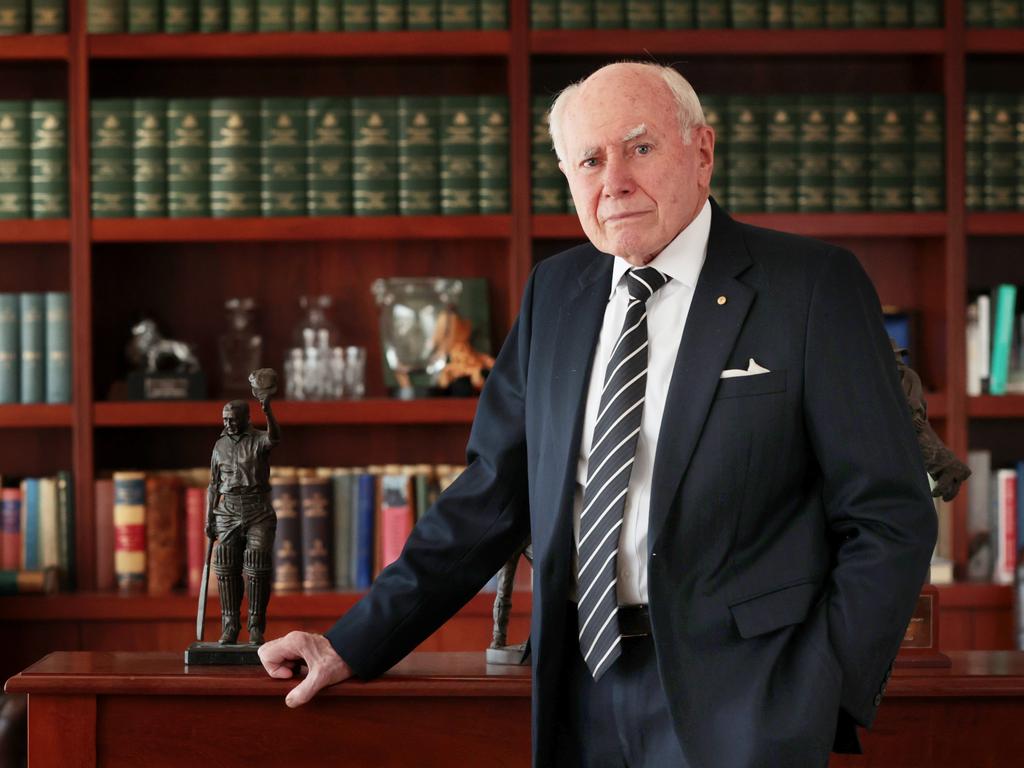

Former prime minister John Howard, a voice critic, nevertheless proposed to recognise Aboriginals as our first Australians in a preamble to the Constitution that failed as part of the defeated 1999 republic referendum.

The voice referendum, let alone truth and treaty, will be a hard process for many Australians to come to terms with, especially recent migrants who have little connection to frontier conflicts.

To listen to Albanese, it’s as if Yes campaigners are being generous demanding a mechanism that could culminate in reparations to the descendants of Aboriginal tribes displaced by white settlers. Yet like it or not, as this column remarked on August 8 last year, the development of international law in this area suggests that even if the voice referendum fails, the Aboriginal political class will eventually secure a treaty via the courts.

Australia has signed the non-binding 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People and treaty making has prospered in Canada and New Zealand. Few journalists seem to be in touch with where the nation’s own legal, historical and academic research sits on this issue.

Even leaders of the referendum No case have previously supported a treaty.

As prime minister in 2013 Tony Abbott, who wanted his own recognition referendum by 2017, spoke fondly of the Treaty of Waitangi in New Zealand. Abbott in 2013 told parliament: “We have never made peace with the first Australians.’’ He believed we should have followed the example of the 1840 treaty between the British government and NZ’s Maori leaders.

The following year, Abbott began his annual Closing the Gap speech in parliament praising former Labor PM Paul Keating’s 1992 Redfern speech. Abbott said he “couldn’t disagree with its central point: that our failures towards Australia’s first peoples were a stain on our soul.” None of this undermines Abbott’s rejection of a voice now but it does raise questions about his concerns that activists may push on for a treaty if they achieve a voice.

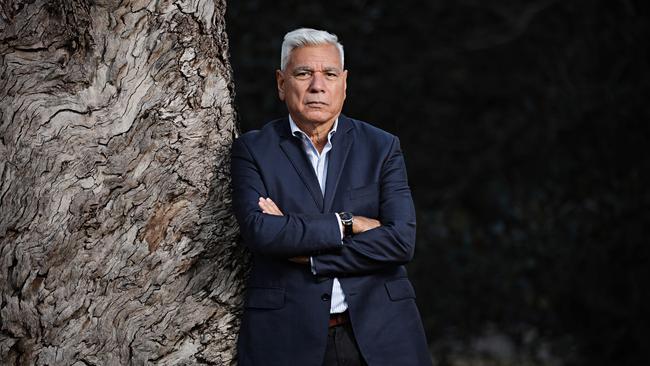

President of the Recognise a Better Way No case group Warren Mundine has also supported treaty making. He told this column last Wednesday he still believes the economic empowerment that could be driven by localised treaties would do more to address Aboriginal disadvantage than a voice.

“I believe treaty gives direct power to the grassroots and is more useful than the voice. The voice is a useless power grab by the people who look to government to solve their problems. It’s about building capacity through education, economic participation, community safety and social norms.” Mundine’s words here certainly expose his Yes case critics of the past week.

A new paper partly written by Macquarie University legal academic Shireen Morris, Imagining a Makarrata Commission, points out “Mundine … has argued that drawn out native title cases should be settled by a broader ‘formal agreement’ that is negotiated ‘between Australia and each Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander group, nation to nation’.”

Morris, an adviser to voice architect Noel Pearson, quotes a 2013 speech by Mundine, Shooting an Elephant: Four Giant Steps, at Garma in August 2013. “Mundine called for a ‘system of governance that recognises the Indigenous nations and gives them the ability to govern matters concerning their traditional lands, assets, culture, language and heritage’.” This is at odds with Howard’s criticisms of treaty making in an interview with this newspaper’s Janet Albrechtsen last week.

Yet by far the most ill-informed, indeed hypocritical, intervention about the voice last week was from former Liberal Party prime minister Malcolm Turnbull. Remember, Turnbull was PM when the Uluru Statement was agreed. He called the voice a “third chamber of parliament” and ruled it out.

That “third chamber” comment has been at the heart of the No case since Albanese’s announcement of the referendum. Turnbull’s latest comments came in an essay he wrote with former ACTU president Sharan Burrow denouncing the voice coverage of this company’s Sky News and its establishment of a dedicated voice channel.

Turnbull and Burrow were writing as co-chairs of Australians for a Murdoch Royal Commission. They claimed the new voice channel would be used to spread division and hate by publishing misinformation about the voice. This from a man who did more to harm to the voice in 2017 than any opponent since.

Turnbull and Burrow claimed Sky News was campaigning relentlessly against the voice. He did not mention host Chris Kenny has campaigned for the change, or the many interviews leading voice advocates have had on Sky News. Pearson appeared with political editor Andrew Clennell the weekend before Turnbull’s attack.

Voice supporters would have approved of the new Sky News channel’s documentary last Tuesday night by NT bureau chief Matt Cunningham. It was fair, balanced and passionate. But the voice is struggling.

Yes campaigners who say it’s time because it took half a century from the successful 1967 Aboriginal referendum that counted their people to the Uluru Statement that proposed they be heard need to remember the fight has been much longer than 50 years.

Our greatest campaigner for Aboriginal recognition, William Cooper, began his lobbying for land rights with his Maloga Petition in 1881. He established the Australian Aborigines League in 1935 when he set out a petition demanding direct representation in parliament, enfranchisement and land rights. He tried to petition King George VI in 1938 but the cabinet of PM Joseph Lyons decided not to submit his document.

Reporting last week about the possibility of a treaty if the referendum for an Indigenous voice to parliament succeeded showed how confused many journalists and politicians are.