Indigenous voice to parliament: Behind the scenes of two very different voice campaigns

As each camp crisscrosses the country to try to sway up to 6m undecided voters, the No group holds a formidable lead in the polls. But the Yes side has one final push planned.

There is just a fortnight to go until the moment of truth for the Indigenous voice, 14 fleeting days for the Yes case to defy history and turn the campaign around.

Two weeks for the No side to bring home a formidable lead in the opinion polls and sink the referendum.

The run-in to October 14 will be frenetic, with the ranking figures in each camp crisscrossing the country to convince a pool of up to six million undecided or persuadable voters to break their way.

We have never seen the likes of this in the history of the federation. For the first time, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are not only the focus of a national electoral contest, they’re in charge of prosecuting the competing arguments as well.

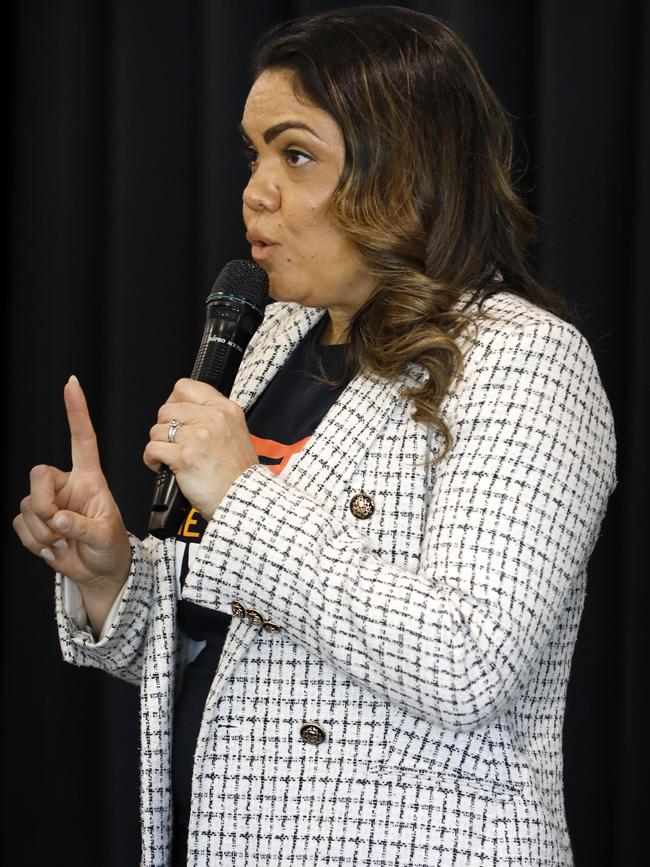

Political stars are being born on the hustings. Neophyte Nationals senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, 42, a self-professed Celtic-Warlpiri woman from Alice Springs, has emerged as the Noes’ most powerful advocate, filling halls and meeting rooms wherever she goes. Already a Coalition frontbencher, she seems to have a glittering future.

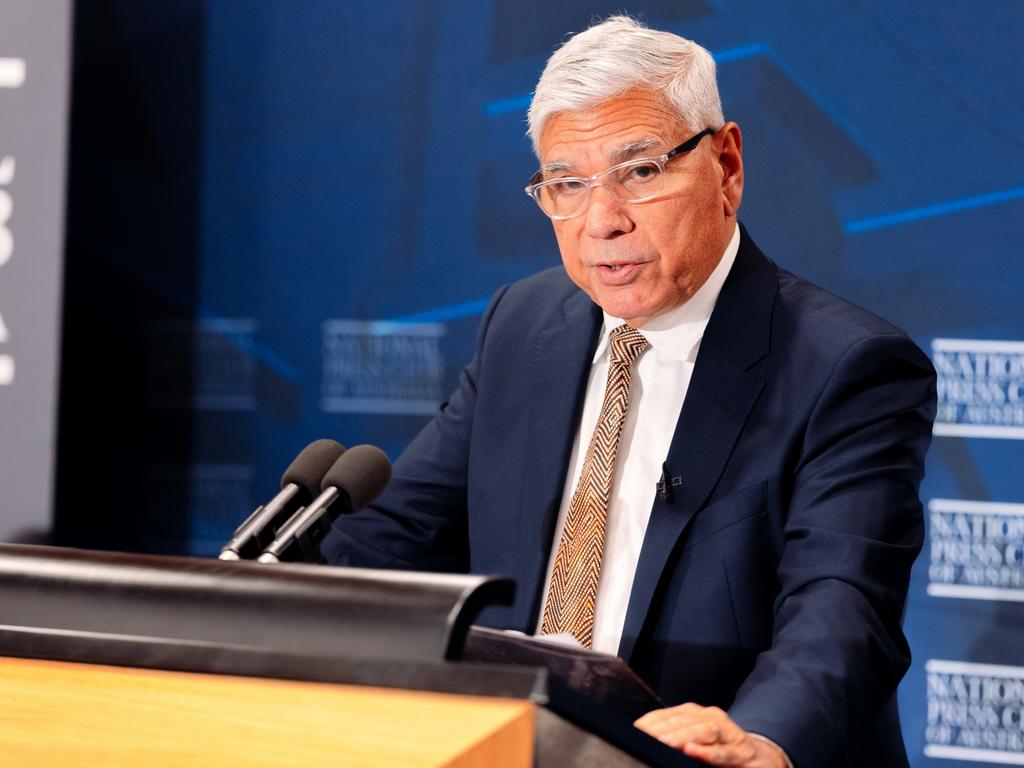

Yes23 is directed and co-fronted by Queensland Quandamooka man Dean Parkin, also 42, a protege of celebrated Indigenous activist and thinker Noel Pearson, the affirmative team’s heaviest hitter. As we will see, Parkin brings both measure and a multifaceted skill set to the push for constitutional change.

This week’s published opinion polls delineated the battlelines for the decisive phase of the campaign. Both The Australian’s Newspoll and the AFR/Freshwater Strategy poll showed that backing for the voice had continued to fall, to 36 per cent and 33 per cent respectively. Newspoll had the No vote up three points to 56 per cent.

On those numbers the referendum is doomed on the popular vote, never mind the associated test of being passed by a majority of states. Hence Yes23’s targeting of the undecideds – just 8 per cent in Newspoll – alongside the soft Noes who might be talked around and the soft Yeses who could be locked in.

What would be even more concerning to the Yes side is the trajectory of the vote: they can’t start to rebuild until the slide is arrested. As one No campaign figure put it: “They’ve got nowhere to go to go until they bottom, and they’re running out of time.”

So here we are on the road with Parkin in Cairns, Far North Queensland. Outwardly, he’s as sunny as the spring weather, a bundle of energy in his lavender Vote Yes T-shirt.

It’s a big day for the team. Pearson is speaking at the National Press Club in Canberra and they’re tracking the fallout from Nyunggai Warren Mundine’s effort there on Tuesday, when the No spokesman branded the Uluru Statement from the Heart that Parkin helped frame a “symbolic declaration of war against modern Australia”.

The Yes man was up with the birds, of course. The operation is set up like an election shop run by one of the major political parties: the morning newspaper and news site coverage is clipped and distributed by the media staff predawn, and the first phone hookup of the national leadership team is at 7.30am sharp to frame the day.

In addition to Parkin, spokespeople such as Pearson and board member Thomas Mayo frequently dial in, along with key backroom players from campaign HQ in North Sydney, including former Victorian Liberal Party director Simon Frost and Paul Murphy, who ran ministerial offices for state Labor governments in NSW before heading the Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance.

The campaign vehicle, Yes23, runs like a public company under co-chairs Danny Gilbert of national law firm Gilbert + Tobin and filmmaker Rachel Perkins, its board stacked with political nous from John Howard’s former chief of staff Tony Nutt, one-time Queensland Labor treasurer and deputy premier Andrew Fraser, and Kevin Rudd’s chief media adviser as prime minister, Lachlan Harris. Business expertise is provided by Wesfarmers chairman Michael Chaney.

Mark Textor’s CT Group undertakes polling and market research while the war chest swells – reportedly to more than $50m to date – much of it donated by big corporations. Those ubiquitous Yes T-shirts and other merchandise have been flying out the door; more than 40,000 volunteers have signed on to door-knock and staff voting stations ahead of the start of pre-polling next week.

The point is that Yes23 is both well funded and expertly led. So why is it floundering, according to the published polls, its support more than halved since Anthony Albanese put the voice on Labor’s to-do list on election night last year?

Parkin tells Inquirer: “People are just starting to turn their minds to this in a serious way right now. That’s been the focus of our campaign right up until this point … knowing that there will be millions of Australians that at the moment are still worrying about paying their rent, putting food on the table.

“Maybe they’ve heard about this referendum thing … maybe they’ve seen a few signs or ads on TV.

“But the sharpening of that focus is going to happen in the last seven to 10 days. And the entirety of our campaign effort is that this is the window of opportunity to target those people.”

Think more. More boots on the ground to distribute Yes pamphlets and canvass voters – and much, much more advertising online, on television and radio directed at the demographics that count most.

The ethnic vote is a priority. Yes23 is set for a record spend for a referendum on outreach to multicultural constituencies, especially the strong Chinese, Indian and Arabic communities in western Sydney that voted heavily against same-sex marriage in the 2017 postal plebiscite.

The received wisdom holds that NSW will be in the Yes column on October 14 with Victoria, anchoring the national vote and delivering two of the four states required for the double majority to pass the referendum.

Queensland and Western Australia are forecast to vote No, leaving Tasmania and South Australia as swing states that could go either way (though Tasmania is leaning Yes in the published polls).

But, as ever in politics, it’s not what the players say, it’s what they do that matters. And the resources the Yes campaign is throwing at the two million-odd voters in Sydney’s multicultural west suggests NSW is far from a given for them.

Equally, WA also may surprise. While Queensland and WA tend to be bracketed for No, they are very different states demographically. Just on 80 per cent of the WA population is concentrated in Greater Perth, while 50 per cent of Queenslanders live outside Brisbane. The city-country divide in polled voting intentions on the voice yawns widest in the deeply decentralised Sunshine State, a point both sides concede.

It’s Tuesday, so it must be Dubbo. Price’s campaign travel is truly dizzying: Sydney on Sunday; on the road with Nationals’ leader David Littleproud to Lithgow, Bathurst and Orange for media appearances and two packed town hall meetings on Monday; rendezvous with Peter Dutton for a pollies-in-the-pub session in Dubbo at which neither the Opposition Leader nor Littleproud could have been in any doubt who the locals wanted to see.

Then a chartered plane hop to Ballina, northern NSW, where Price again pulls an admiring crowd. When we catch up over a hurried lunch, she barely has time to eat her chicken wrap. “Sometimes I forget that I’m sort of known in places,” she says, abashed. “Yeah, delightfully surprised at that reception.”

Team No benefits from having the vastly simpler case to argue. Don’t know what the voice is? Vote no. Worried about what it will do? Vote no. Concerned about the fuss it’s creating? Vote no.

The No side doesn’t need a mandate and offers no agenda. It doesn’t have to present a unified front; a little division in the ranks actually allows it to cast the net wider.

But don’t take anything away from Price. She performs with the aplomb of a seasoned campaigner, holding her own in lengthy Q&As with those most testing of inquisitors, the voting public. What a change: she actually answers the curly questions thrown at her.

Take this exchange in Orange on Monday night. The community forum had been hurriedly switched to the stately Duntryleague Golf Club after the original venue cancelled, claiming a booking mix-up. NSW state Nationals MLC Sam Farraway wasn’t buying it. “I don’t think we’re welcome there,” he said, geeing up the 250-strong audience.

A 70-year-old Indigenous man, Neil Ingram, climbed to his feet and announced he would be voting No. There were already too many bureaucracies in Canberra, he said, to murmurs of approval. But as a Stolen Generations survivor he couldn’t accept Price’s contention that colonisation had mostly improved the lives of First Nations peoples, not when his grandmother was taken from her family at age 14, raped, and further traumatised after becoming pregnant with his mother. “I find your comments to be offensive and totally incorrect,” he told the impassive senator.

She replied by recounting the story of her own grandfather, a traditional man who had been taken to Alice Springs in chains for spearing a goat and put to work constructing army installations.

Instead of complaining, he would say years later how proud he was to have helped build the outback town. “Now the way I see it, there’s not a group of humans on the face of Earth that hasn’t experienced trauma of some sort in their lives, in their immediate families, in their ancestry and so on, so forth,” Price said. “But I find it isn’t incumbent upon me as an Indigenous person to … pass on the trauma to the next generation and the next generation. My grandfather taught me to be strong and to not view myself as a victim to anybody, regardless of what adversity I might experience through my life.”

The ongoing trauma of domestic and family violence in remote Indigenous communities wasn’t the legacy of colonisation and it wouldn’t be addressed by the voice. It was the responsibility of individual perpetrators and “we need to be realistic in how we approach these issues”.

Price continued: “The acceptance of violence, things like cultural payback where, you know, it is thought that any premature illness of death is caused through sorcery and therefore somebody must have to be held responsible and … the fact that there are still girls being married off in arranged marriages, these practices are contributing in places where that are experiencing the highest rates of domestic and family violence.”

You can see why political progressives find her views jarring. Price tells Inquirer she is living proof Australia can move on from the troubled history of settlement and frontier. Her mother, Bess Price, is a no-nonsense Warlpiri woman who served as a minister in the last Northern Territory Country Liberal Party government; dad Dave, a teacher from Newcastle who took on the challenge of working in Indigenous communities as a whitefella, says he is glad his daughter learned long ago how to look after herself. (She has a brown belt in Taekwondo and is proficient at kickboxing.)

Asked how the No side will approach referendum day, Price says: “I think the message remains the same … that we shouldn’t be divided along the lines of race in our Constitution. The fact is … everyone wants what’s best for everybody in this country. No one wants to be treated any less.”

The No campaign is a very different beast to Yes23, though it also draws on the expertise of proven political operators such as Nationals federal director Lincoln Folo.

The key groupings are Recognise a Better Way headed by Mundine, of the Bundjalung people of northern NSW, the Noes’ sometimes problematic punch-thrower who served as ALP national president before jumping to the Liberals to run unsuccessfully for federal parliament, and Fair Australia, an offshoot of the not-for-profit conservative lobbying organisation Advance, backed by Price.

They lack the reach and resources to match the affirmative side’s ground game. In Cairns, Yes23 regional campaign director Stacee Ketchell says her volunteers are yet to encounter a single team of rival door-knockers. “We get asked all the time, where’s the No people?” she says. “As far as I can tell, they don’t physically exist … they are just online or in the media.”

Parkin has been doing the rounds to fire up the troops, meeting team co-captain Talicia Minniecon at community service DIDGE, Deadly Inspired Youth Doing Good, a hive of activity in suburban Cairns. To date, Yes23 door-knockers have visited 250,000 homes nationally and made more than a half-million phone calls. There’s plenty to do if the campaign is to reach the 30 per cent of voters it believes to be in play still.

Parkin doesn’t dispute the public opinion polling but insists Yes can prevail. As editor-at-large Paul Kelly observed in The Australian on September 20, passage of the referendum would be a historic departure from constitutional conservatism, smashing “one of our deepest orthodoxies – that the Constitution transcends contemporary and popular renovation”.

Parkin says Yes23 is finetuning its messaging to hit “the right market, the right audiences where we need to persuade voters to jump on board.” He conducts a long phone interview with Sydney Chinese-language radio station 2AC, waiting patiently while his answers are translated into Mandarin and Cantonese.

Next stop is a door-knocking drive in Edge Hill, a leafy pocket in Cairns’ north. The targeting is precise. Booth results from last year’s federal election are crunched with census data and campaign research to guide the field teams; this one is 14-strong. Before setting off, the volunteers are briefed in a park by Queensland Council of Unions organiser Steve Blacklow, underlining the importance of the trade union movement’s contribution.

He tells them to be respectful. Don’t waste time arguing with people who have made up their minds to vote No and, above all, be safe.

Parkin is handed a kitbag containing Yes23 pamphlets to be left when no one was home, campaign stickers, buttons and a pen to keep tabs of the addresses. Paired with Angelique Scott, an experienced Labor Party campaigner, he knocks on 12 doors, two of them opened by confirmed Yes voters.

A bare-chested man regales them for 10 minutes from his front yard; a maybe, Parkin says, who they may have got across the line. Another local, out for his afternoon walk in a red polo shirt, sternly waves them away.

“I’m a No voter,” he snaps. “Don’t come near me.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout