The Indigenous voice to parliament is a political ploy to grab power

Next month’s referendum is one of the most important in Australia’s history. Australians will have a choice. A choice about what kind of nation we want to be.

Do we want Australia to be a liberal democracy, where all people are equal? And where all Australians can be reconciled and moving ahead, united?

Or do we want to be a country where people are divided by race — permanently in conflict with each other over facts of history that cannot be altered?

This second pathway is the agenda of the Uluru Statement’s authors.

This referendum presents additional choices for Indigenous Australians. Do we want our traditional nations, our mobs, made into one homogenised group? Do we want to be segregated again as a race of people in the Constitution? Do we want traditional owner rights usurped? Do we want to cede the fundamental principle of our cultures that no one speaks for another person’s country?

Because that’s what this referendum and the Uluru Statement is all about.

This month I have a four-part series of articles in the Daily Telegraph written with Dr Vicki Grieves Williams on the Uluru Statement — both the 439 words on the canvass and the 26-page manifesto that sets out their agenda — which we describe this as a symbolic declaration of war against modern Australia.

The canvass is a glossy marketing brochure for the misappropriation of culture, a misrepresentation of history and for a radical and divisive vision of Australia; all done in the name of Indigenous Australians but working against us.

Nearly a decade ago I gave a speech on Australia Day about reconciliation. I spoke about the difficulties people have moving on from historical grievances and how I thought that could be overcome. The ABC brought this speech into focus again recently, trying to frame it as a fracture in the No campaign.

I should thank the ABC for giving it renewed attention. Because my speech highlighted a lingering cloud that shadows the choices we face. The theme of the speech came from my Catholic faith. Reconciliation is about absolution from past sins, and it has two parts — sorry and forgiveness.

I said, in this country we talk a lot about the sorry part, but we never talk about the forgiveness part. I said it’s not enough that Australia says sorry; Indigenous people also need to forgive Australia as a nation.

Many Aboriginals feel angry about past wrongdoings. But those events can’t be undone. So as Aboriginals, we have a choice: to continue to feel aggrieved or to draw a line in history and not be captive to the past. Always remember. Learn from it. But move forward.

The Uluru Statement couldn’t be further from the idea of reconciliation. The full manifesto is steeped in grievance. It sees Indigenous Australians as trapped in victimhood and oppression, not free or able to make their own decisions; that self-determination is an unrealised aspiration. This is a lie.

It includes a self-proclaimed History of Indigenous Australia called ‘Our Story’, written to shame Australians about their non-Indigenous ancestors and Australia’s founding.

No nation had a perfect beginning. Most had bloody and brutal beginnings, founded in invasion, conquest, revolution or war. I don’t judge a nation by the worst of its history but by how it seeks to become its better self. And by that measure, I judge Australia well.

I can’t think of any nation that has overcome the conflicts and injustices of its past better than Australia. We have taken the best of our history and built a nation where everyone is equal; where any person, regardless of their origin, can aspire to and achieve the highest.

When my parents were first married, they lived in a bark shelter on the Mann river. My oldest brother Roy took his first steps there. As a young man Roy joined the army and served all over the world. He was severely injured in Vietnam, losing his leg.

He was Mentioned in Despatches for his bravery and is highly decorated for his service to our country—including the Medal of the Order of Australia (Military Division). In 2016 he was named the Australian Army’s first Indigenous Elder.

Bess Price was born in the desert in central Australia. She was her mother’s ninth child. Four of her siblings died in infancy. When Bess was born, she was tiny and sickly. Her mother left her to die. But she was saved by another woman in the community. Bess lived most of her childhood in humpies. She was promised in marriage to be the second wife of her sister’s husband, but persuaded her father against it. She had her first child, a son, to another man at 13. She experienced violence and later the death of her son from cancer.

And you know what? Bess graduated from University, and she went on to become a Minister of the Crown in the Northern Territory government. She is a Member of the Order of Australia.

Let that sink in. She began her life in the worst of circumstances and today she’s a Member of the Order of Australia.

These are two people who I love and admire. Australia is a nation where a child born under segregation and living in a humpy can go on to great achievement.

I was born in the 1950s, in regional New South Wales — one of 11 children. I grew up in poverty. For the first 13 years of my life I lived under segregation — like all Aboriginals. We were controlled by government protection boards. These segregation regimes were put in place in the 1800s by well-meaning people, who thought Aboriginals couldn’t take care of themselves. These bureaucratic segregation systems controlled every aspect of our lives.

My father couldn’t have a drink in a pub after cricket with his mates. His wages were taken by the government, and he was paid an Aboriginal allowance. Aboriginals in New South Wales were subject to a 5pm curfew. My Dad was arrested for breaking curfew coming home after working late.

Authorities could walk into our homes without notice. One day a welfare board officer walked into our home. Mum had had enough and chased him out of the house with a broom. She said, “We own this house and you can’t come in!”

These protection regimes kept us down and held us back from a full Australian life.

They were abolished after the 1967 referendum, when Australians overwhelmingly voted to remove racial segregation from the Constitution, for everyone to be equal under the law.

Now, the Albanese government wants to put racial segregation back into our Constitution.

No other group of Australians would have a body entrenched in the Constitution to speak on their behalf with a single voice. Only one race of people would be treated in this way.

This month Senator Jacinta Price, Senator Kerrynne Liddle and I are talking to Australians all over the country. We’ll be urging them to vote No in the referendum.

All three of us are Aboriginal and we all oppose the voice. We believe Australia is a great nation and that all Australians, including Aboriginals, can be proud to be a part of it. We believe Indigenous Australians are not condemned by their past and certainly not by the experiences of their ancestors.

And we believe traditional owners should be able to speak for themselves about how they want to live their lives on their own countries, not told what to do or what to think by some centralised overlord, be it the Central Land Council or the voice or a Makarrata Commission.

The Yes campaign is out there every day accusing the No campaign of lying. But the Yes campaign is built on a pack of lies.

One lie, is that Indigenous people don’t currently have a voice — that Indigenous people aren’t listened to in making laws and policies. It’s the opposite.

Indigenous people have many voices. Hundreds of Indigenous organisations are immersed in policymaking affecting Indigenous Australians. Corporations, sporting codes, religious groups, unions and every arm of local, state, territory and federal government, every agency and bureaucracy have Indigenous advisory bodies or other formal consultation. Nothing happens on Aboriginal land without consultation with traditional owners through native title and land rights legislation.

There are more Indigenous parliamentarians today than ever before, including the Minister for Indigenous Australians. And there’s no door in Canberra that isn’t wide open to Indigenous Australians who want their voice heard.

Another lie is that the voice will give good advice. Indigenous bodies can give bad advice, like the Coalition of the Peaks who advocated against cashless welfare cards. They don’t have all the answers.

Another lie is that the voice is just an advisory committee. It’s not. It is an entrenched, permanent, political right to make representations to the Parliament and the Executive. Distinguished professors of constitutional law told the Parliamentary Committee the voice will have, quote unquote, “similar constitutional status” as the Parliament, the Executive and the High Court. But, unlike those institutions, no one knows what the voice is.

When the constitution was written, we had hundreds of years of precedent under the Westminster system. So we knew what a High Court is, what a Parliament is and what the Executive is. We have no idea what a “voice” is.

Another lie is that 80 per cent of Indigenous people want the voice and it comes out of a grassroots Indigenous movement. Even ABC Fact Check said that claim doesn’t stack up. Many Aboriginals have never heard of the voice, especially those in remote and regional Australia who are most in need. Many Aboriginals are voting No.

The Regional Dialogues, leading up to the Uluru Statement, were attended by a small number of Indigenous people, hand-picked to “ensure consensus”.

Megan Davis let the cat out of the bag when she said the Dialogues did “rubber stamp” the voice.

Another lie is that the voice will change Indigenous lives for the better. Read the official Yes pamphlet and the voice sounds like some magical wand that will solve all the problems if only we just let it.

Prime Minister Albanese has said “If you vote No, you’ll get more of the same.” Actually, if you vote Yes you’ll get more of the same. But it will be in the Constitution. Albanese says the current approach has failed. The voice will take the current approach, wrap it in more bureaucracy and entrench it in the Constitution — forever.

If the purpose of the voice is to end disadvantage, it shouldn’t be in the Constitution. Because that’s permanent. That says Indigenous Australians will always live in poverty. That we will always need help. That we are destined for permanent disadvantage. That’s exactly what people thought in the 1800s when they set up the protection regimes. When they set up segregation.

The fact is, most Indigenous Australians are doing fine. They go to school, go to work, run businesses, take care of their families. And they aren’t in prison. They don’t need a special Indigenous voice. It’s wrong to tell young people, growing up in these families, that they are disadvantaged because they are Indigenous. It’s wrong to tell them — as I have heard many times during this campaign — that they are more likely to go to prison than to university. Because it’s just not true.

Where we need to focus is on those Indigenous Australians who are struggling. Most of them are living in remote communities or are trapped in intergenerational welfare dependency, or both. The voice will not help them.

The biggest lie of all is that the No Campaign — people like Senator Price, Senator Liddle and myself — have no plan or even don’t want to improve Indigenous opportunity.

I don’t believe anyone in this country wants to see any Indigenous Australians continue to struggle. Certainly not us. We have devoted most of our adult lives to advocating for, and supporting, Indigenous people in need. We have battled opposition, disinterest and vested interests. We will continue to battle.

But nothing will change unless there is a focus on four critical areas.

Firstly, there needs to be accountability.

Governments have spent billions. Where is all this funding going? What is it being used for? What outcomes have all those community organisations and service providers who receive all this funding, actually achieved?

Secondly: education.

The same year I delivered my Australia Day speech, the Forest Review: Creating Parity was released. It contained a very interesting fact: There’s no disparity for Indigenous Australians who are educated at the same level as other Australians. So, if you want a simple idea to close the gap, it’s getting all Indigenous children to school.

Just imagine if every Indigenous child went to school every day. Think about what a profound impact that would have.

We have celebrities, corporates, law firms, sporting codes, religious groups, local, state, territory and federal governments, unions devoting massive time and money campaigning for the voice. Imagine if they devoted all of that energy to getting Indigenous children into school.

Sadly, I know from my own experience advising governments and dealing with bureaucrats, education departments and teachers’ unions that many of those who have the power to achieve this one goal don’t use it as they could.

The third area is economic participation. Growing up the way I did, I learned the only solution to poverty is economic participation. I saw this with my parents and grandparents who were determined to own their own home and to ensure their kids got educated and into employment. This made all the difference for us.

I don’t know any group of people in the world that has lifted out of poverty without economic participation. If every Indigenous child went to school and every Indigenous adult went to work there would be no Gap.

Fourthly: social change. This requires confronting some hard truths. People need to stop turning a blind eye to the violence, abuse, coercive control and destructive behaviour that goes on in some Indigenous communities.

Senator Price, Senator Liddle and I have been speaking about these problems for years. For their efforts, Senator Price and her mother Bess Price have been subject to some of the most racist and misogynist abuse.

When was the last time any of the large corporates barracking for the voice raised awareness about violence and abuse in remote Aboriginal communities? When will Qantas paint one of its planes with a call to confront the violence and abuse of Aboriginal women and children in remote Australia?

If we as a nation are sincere about closing the gap, we need to deal with what I call the enthusiasm gap. Lots of well-intentioned people are enthusiastic about the symbolism of the shiny new thing — the voice. But when it comes to doing the challenging work on specific areas of need, the enthusiasm wanes.

That’s human nature, I suppose. And it is a truism that applies beyond Indigenous concerns. But, if we really want to better the lives of our most disadvantaged Australians, we have no choice but to stay engaged for the long-haul.

Accountability, education, economic participation, social change. These are not complicated ideas. But they require political will to achieve.

The voice referendum will be a choice between two opposite visions for Indigenous Australians.

One is a vision of segregation, bureaucratic control and dependency, and a mindset focussed on historical grievance and identity politics.

The other, is a vision of economic participation, financial independence and self-determination, and a mindset focussed on jobs, education, social stability and practical initiatives. This is the vision of Jacinta Price, Kerrynne Liddle and myself, and many other Aboriginals who oppose the voice.

The voice is not about whether Indigenous Australians are recognised, respected or listened to. And it’s certainly not about how to improve the lives of Indigenous people.

I believe many well-meaning Australians support the voice because they believe it will solve problems. Because they believe Indigenous people want it. And because they want to see something positive and symbolic develop in the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. Sadly, I think many Australians also feel they must support the voice because of misplaced guilt about Australia’s history.

But I don’t think all of these supporters have grasped the path this referendum is taking us down. I believe that they don’t see the threat that the voice poses to Aboriginal traditional owners and to the character of Australia itself.

The voice is a political ploy to grab power, not just from the Australian nation but also from traditional owners. We know from the Calma-Langton Report that the voice is intended to be a vast, expensive new bureaucracy interposed at every level of government decision-making.

In 1967, we fought against segregation and to get bureaucrats off our backs. We don’t want them to return.

Senator Price, Senator Liddle and I were all born in remote and regional Australia. Our lived experiences and those of our families include growing up on missions and reserves, segregation, the experiences of the Stolen Generation, poverty, violence and mistreatment by authorities — all the things activists today are so aggrieved about.

We have also seen the good of this nation and the good of its people and its institutions, and the great promise it offers to all Australians. Our stories are testament to this. All of us must work harder to create the opportunities for other stories.

We oppose the radical and divisive voice. That pathway will not lift Indigenous Australians. It will not reconcile Australians. It will only divide us and keep us that way. That is why we are voting No.

Thank you.

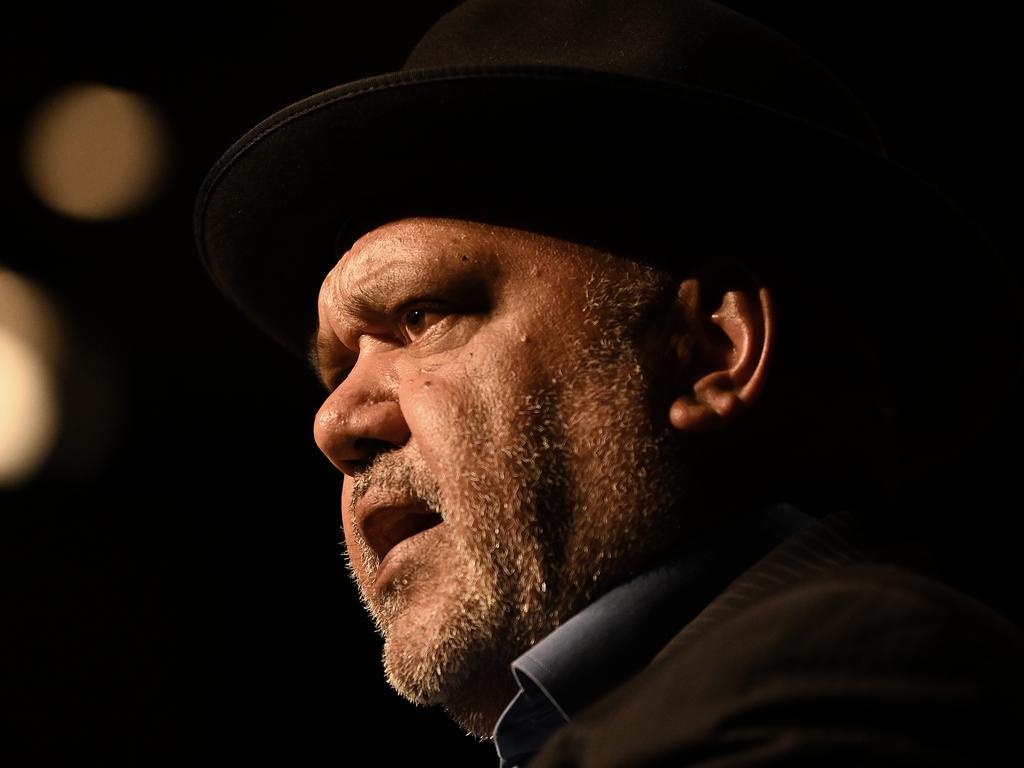

Nyunggai Warren Mundine delivered this speech at the National Press Club in Canberra on Tuesday.

This is the first time in my 30 years of public life that I’ve been invited to address the National Press Club, and I appreciate the opportunity.