Indigenous voice to parliament is solution looking for problem to solve and will only divide

The voice will interface with every level of the commonwealth government apparatus, with every decision and policy subject to delay and/or judicial challenge if it is not paid proper homage.

It’s inherently undemocratic for parliament, ministers, the public service and every government agency to be beholden to an unelected body.

But even within the Aboriginal population, the voice won’t be a democratic instrument. Its members won’t be elected; but chosen by committee.

How the membership of the voice will be determined is perhaps the most astounding of all the eye-opening revelations that emerge when a forensic torch is applied to the 2021 Indigenous Voice Co-design Process Report to the federal government by Tom Calma and Marcia Langton, the 3cm thick document that outlines the intended design of the voice.

The report proposes 22 new Indigenous “regions”, which will each send a representative to the national voice. Aside from the Torres Strait Islands, and maybe Tasmania, the voice regions have been set with no nod to cultural divisions at all and bear no resemblance to actual First Nations across Australia. These new regions will not just be geographic boundaries but will in fact be new Indigenous groups. Groups that will take on a life of their own and no doubt come to dominate Aboriginal politics.

Within those boundaries we already have land councils and native title traditional owner representative bodies (each of which have their own territorial reach) and a huge number of community organisations and Aboriginal-controlled service providers.

NSW, for example, which has the largest Indigenous population of all the states and territories, will be somehow divided into two regions plus some arbitrary “remote” region created in the far west of the state. There’s no indication of how and where the borders will be applied. And I can tell you, I see trouble no matter where they’re drawn.

This schema is also applied to Queensland, Northern Territory, Western Australia and South Australia. That makes 15 regions. Torres Strait, Tasmania and the ACT have two each. Then there is a “region” created for all Torres Strait Islanders who live on the mainland, who can also be part of the selection process (via community organisations) for representatives from other regions based on where they reside.

So how will each of these “regions” choose a representative for the national voice? The answer is astounding.

The co-design group rejected the idea that national voice representatives should be elected. One reason they rejected it is that a low voter turnout would threaten “the legitimacy and authority of the national voice”. They were certainly aware of the lessons from ATSIC elections, when the voter turnout was less than 40 per cent of the Aboriginal enrolments and in certain jurisdictions as low as 10 per cent. But if the authority of a national voice cannot be assured by a democratic process, where does the voice draw its legitimacy from?

Representatives of the voice will in fact be chosen by the huge number of disparate Aboriginal organisations located within the regions. And they are expected to do this by consensus. How, exactly, I’m not sure. There are many infographics and breakout boxes in the report you can take a closer look at. And get even more confused.

There is nothing to be gained from glossing “Indigenous” people in rural, urban and remote Australia, or in any state or territory, as homogenous, and of one mind. We’re not the Borg from Star Trek. And the idea that the huge number of different, often competing, Aboriginal community organisations across vast regions can come to consensus on anything is laughable.

More to the point, why should people have to join a local Aboriginal organisation to be heard? My lead researcher on this series of papers, Dr Vicki Grieves Williams, told me of a conversation with an Aboriginal friend who said she supported the voice “because we have to have something, there’s nothing happening”. She was shocked she’d have to join a local Aboriginal organisation to have input into the selection of her region’s representative. The friend concluded she would be unlikely to be involved, telling Vicki: “I’m not a joiner.”

This didn’t surprise either of us. In our experience, many Aboriginal people are not. I see many Aboriginal organisations controlled by factions, with family and kin allegiances privileged over anything else and people only joining organisations controlled by their own family or to take over from another.

Far from giving Aboriginal people a voice the proposed model will disenfranchise many of us. I predict endless politics and factional brawling, and organisations caught up in power plays for the large amount of funding and resources that will come with the voice. Many Aboriginal people will want to stay right out of it.

There will be even less focus on real improvements as funding is chewed up supporting blackfellas to talk (and fight) among themselves and with everyone else. Aboriginal people don’t need this artificial imposition on them, to take their energies away from what truly matters.

The whole premise of the voice is that Aboriginals want and need it. But the voice’s own architects are afraid Aboriginal people won’t bother to participate in its elections.

The voice is a solution looking for a problem, demanded by a minority of Aboriginal elites. It will not help communities. And it will not reconcile our nation. It may well help tear those communities and our nation apart.

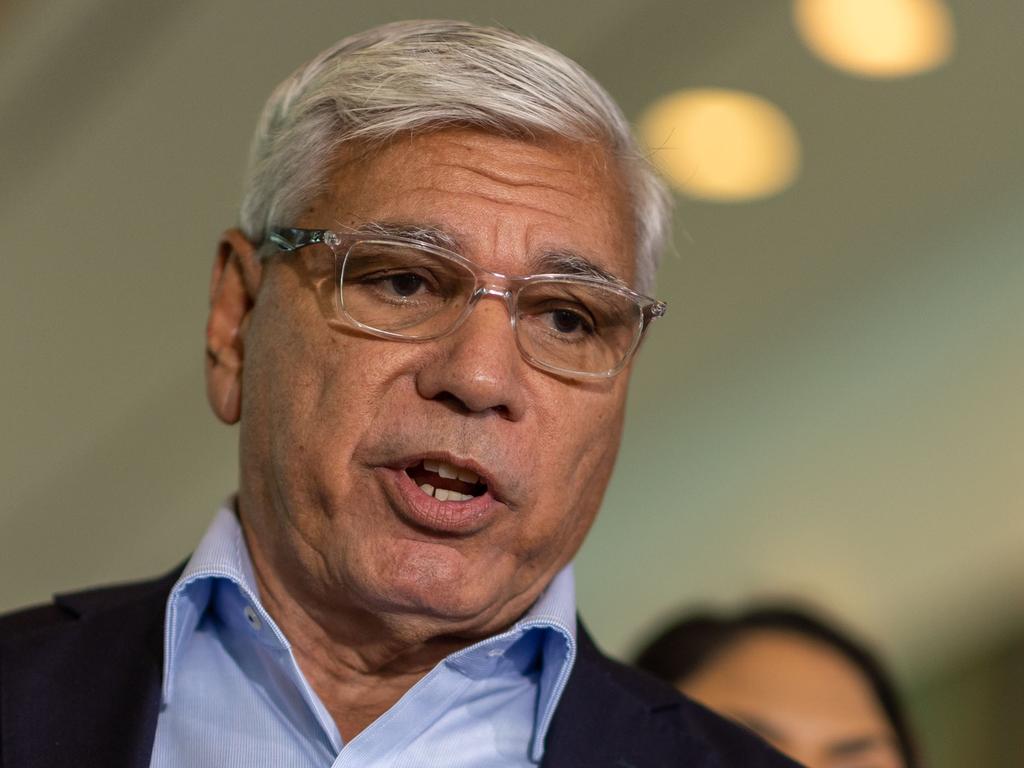

Nyunggai Warren Mundine is director, Indigenous Forum, Centre for Independent Studies, and president of Recognise a Better Way. Acknowledgments to Dr Vicki Grieves Williams, academic, historian and Warraimaay woman for her research and contribution to this series of articles.

This year Australians will vote to introduce a constitutionally enshrined, vast and expensive new bureaucracy called the Indigenous voice to parliament.