Why we need to revive the ethos of the old-fashioned collector

The old art collector had a house filled with paintings, sculptures and ceramics. Unlike today’s equivalent, who buys ‘investments’, this collector was driven by love and an appreciation of art.

Looking through the recent press release from Creative Australia, the new brand name for the Australia Council for the Arts, was like sinking slowly into a quicksand of viscous and slippery verbiage, designed not to enlighten but to submerge the reader. But such an experience is all too common, especially at the confluence of politics and culture. Hardly anyone uses language to discover or seek truth; for many writers, and for all those who write publicity and promotional texts, it is an instrument to conjure up illusion, a tool of deception and manipulation.

As for the content, if it can be called that, it mirrors the style in its vacuity. The trouble starts from the word “creative”. Its spontaneous connotations are childish, recalling the way we speak of pupils in primary school doing something clever; or trivial, as when we admire an improvised handyman solution. But the word has in recent decades acquired more misleading connotations, as an umbrella term that allows advertising, fashion and other purely commercial activities to be assimilated to the traditional categories of high art.

It is thus no surprise to encounter overtly commercial language in the press release: “Creative Australia will be a bigger, bolder champion and investor in Australian arts and creativity” – the two terms tellingly yoked together – or to find the Australia Council now characterised as “the Government’s principal investment and development agency”. The change of branding is claimed to be “a transformative step in the evolution of the organisation … heralding … a bold new chapter for arts and creativity”. As we can see, no cliché has been spared. I think we get the idea that the initiative is a bold one. Bold and creative.

This transformative step is itself the “centrepiece” of the government’s National Cultural Policy, with the flaccid and wordy title: “Revive – a place for every story, a story for every place”. Does culture in our country need to be “revived”? And as for the slogan, it is obviously designed to be “inclusive”, the most important of all buzzwords in the past few years, but it tells us little or nothing about what art is for, or why we should value it, or what criteria we should employ in assessing it.

We are told it will “connect Australian stories with audiences”, but this seems like a limited and parochial mission, a marketing executive’s view of the destiny of a nation’s art. What about the art and literature of other times and places? The cultural memory of the many peoples from all over Europe and Asia who now compose the Australian population? And what about art, literature and music as vehicles by which the human mind comes to know itself better and to gain insight into the experience of other living beings?

Apparently “Creative Australia will bring the drive, direction and vision that Australian artists have been calling out for,” although most artists don’t actually want bureaucrats to provide any of these things. They want the arts to be funded, but they don’t want to have the state’s conception of “drive, direction and vision” imposed on them, as though they were the puppets of an authoritarian régime. There is already too much effective collusion between funding agencies and funded institutions in promoting preferred ideological positions, and with new threats of web censorship and other political restrictions on free discourse, we should be wary when governments attempt to set the agenda for artistic and cultural activity.

One thing that it would be desirable to revive in Australian culture is the ethos of the art collector which, as many people have observed, seems to have declined over the past couple of decades. The old kind of collector had a house filled with paintings, sculptures and ceramics; not necessarily enormously expensive pieces, but ones that were loved and appreciated. Today’s equivalent is more likely to buy work as an investment, and that limits the market to expensive pieces, as well as encouraging the overproduction of investment product such as the notorious APY Collective works that are said to sit in many a self-managed super fund. And at the same time contemporary art has become the pretext for various art bars, parties and other opportunities for well-to-do young people to socialise in a culturally chic ambience.

Occasionally the old-fashioned collections are preserved in house museums, such as the Roche Museum or Carrick Hill, both remarkable places in very different ways, and both in Adelaide. It is impossible to visit Carrick Hill without being impressed by some of the pictures and sculptures in the collection – this time it was Epstein’s bust of Einstein that particularly struck me – but perhaps above all by the intimacy with which these pictures are integrated into the house and lived with.

Carrick Hill has an interesting exhibition at the moment, which also arises from a period when artists were supported by collectors, with virtually no involvement from the state. This is a survey of modernist painters in Adelaide in the 1950s and 1960s, including a combination of local artists and a number of central Europeans who arrived in Australia after the Second World War – such as the printmakers in Geelong I discussed a couple of weeks ago.

Perhaps the most disconcerting thing about this exhibition is how unfamiliar almost all of these artists are today.

It is sad to think of the energy painters put into making these pictures, of the excitement of exhibition openings, the interest of collectors, the commentary of critics, the pleasure that the owners of these paintings no doubt had in their possession, and then to realise how almost completely they have been forgotten.

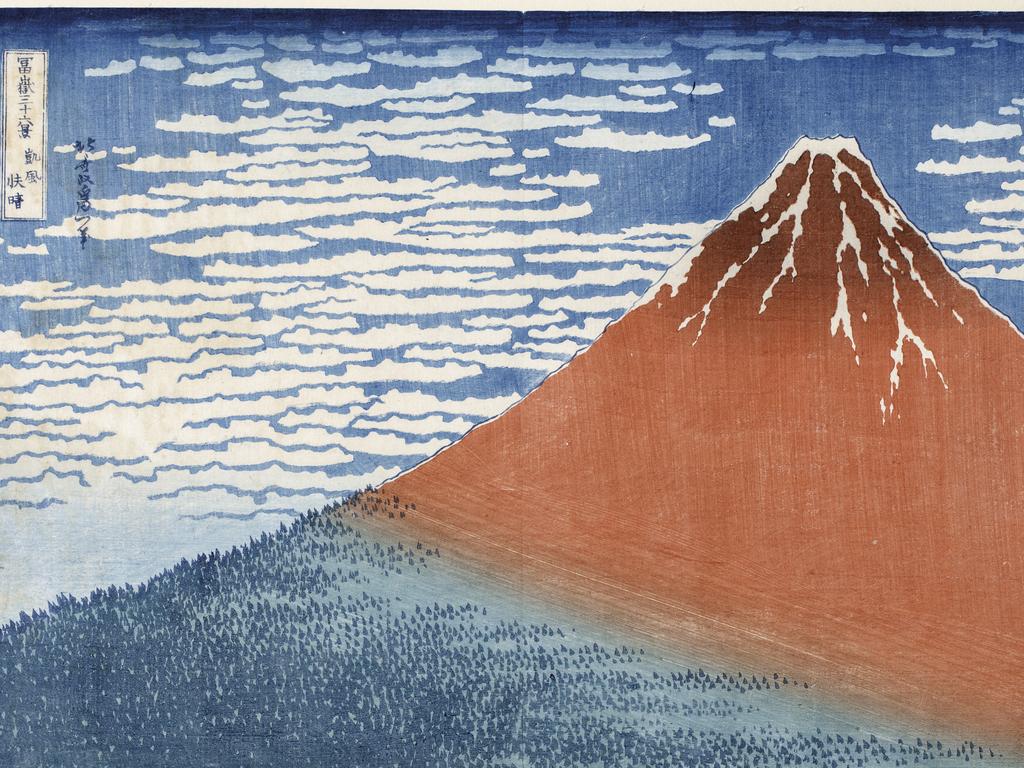

But of course this is not just the cruel and inevitable effect of time, for many other pictures in the house collection have stood the test of time. To take just one example, there is a modest Drysdale downstairs, not a great painting, but one that stands up today as well as it ever did, and much better than any of the pictures in the exhibition itself. It is clear and articulate in structure, yet evokes both the artist’s characteristic vision and the mood of an outback town.

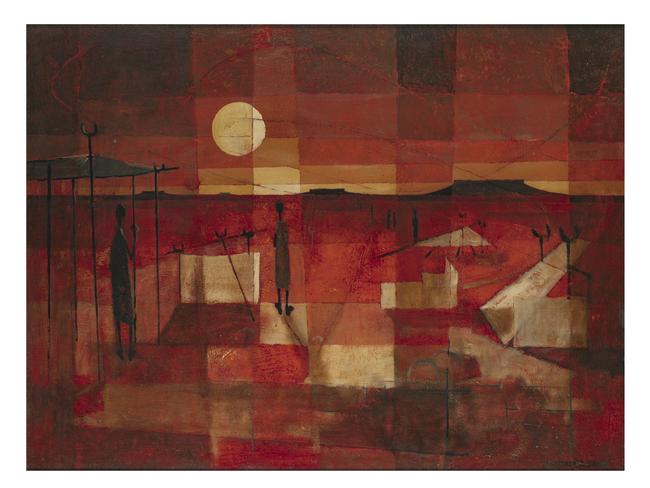

How can we explain this? In the first place, none of the pictures in the exhibition has Drysdale’s articulacy, even though several betray his influence. In the first room, in fact, are two pictures that are specifically indebted to him. The more obvious one is Lawrence Daws’ Alcheringa (1955). He has taken motifs directly from Drysdale’s pitiless burnt outback scenes with their deep rust-red colour scheme, but he has turned them into a semi-abstract pattern.

The whole surface of the picture is divided into a grid of rectangles, and the colour varies arbitrarily from one to the other. The figures are formulaic and placed like design elements. The result is not only derivative of Drysdale, but turns his human and living compositions into a stiff and self-conscious construction. The artist has achieved a certain quality of elegance in a modernist composition, but at the cost of draining the life from Drysdale’s world.

The other picture that is heavily indebted to Drysdale is Jacqueline Hick’s Australian landscape (c. 1960). The composition directly recalls Drysdale’s paintings of the drought-stricken outback made during the war – again a similar colour scheme, and even the ruined houses and sheets of corrugated iron fallen from their roofs. This seems to be one of the best pictures by this artist who was a friend of Jeffrey Smart, but whose work is seldom very impressive.

Here, though, the general movement of the composition is quite strong, but one may still wonder why it is so lacking in definition and clarity of articulation. And since this is a question raised by most if not all of the work in this section of the exhibition, it is worth considering what reason there could be for such a lack – especially as this is a large part of the reason why the work of these artists has not survived in the same way as that of Drysdale.

No doubt this has much to do with the trauma of the war; perhaps they felt it was no longer possible, in the aftermath of that trauma, to be clear and articulate, or to engage with the visible world in the rational and analytic spirit that ultimately goes back to the great innovators in the art of seeing the world of the renaissance. Perhaps it seemed that all one could do in the shadow of the war was either stammer or scream, or to let go of rational process and throw oneself into an irrational and intuitive communion with the subject.

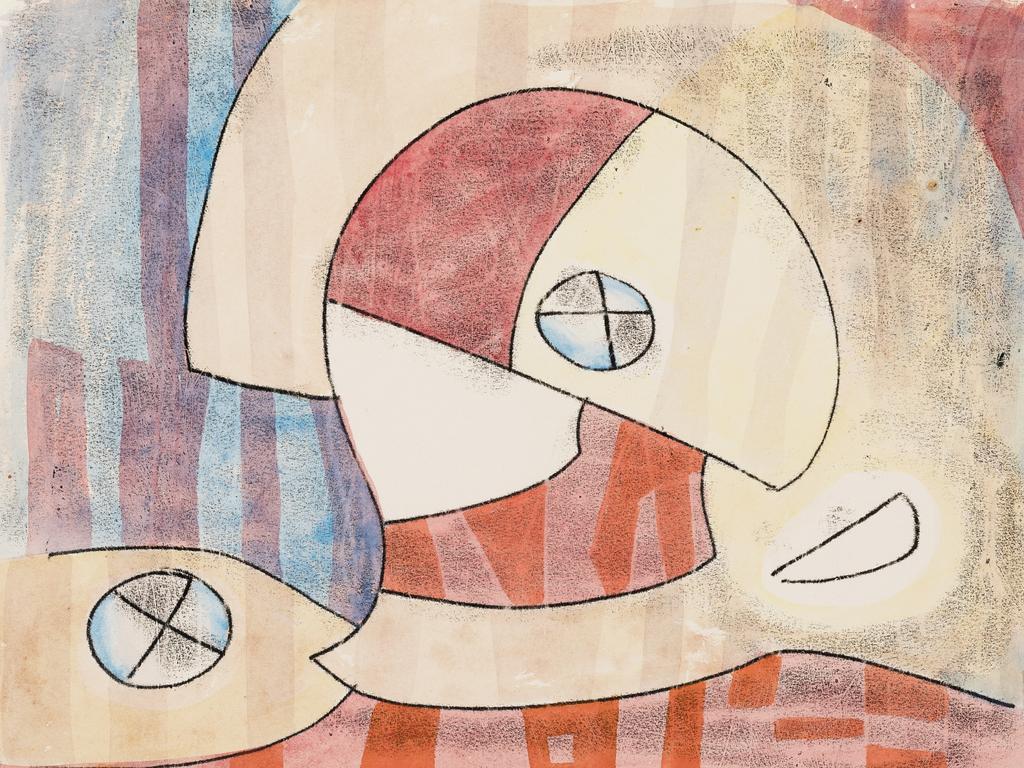

Hence deliberately loose and gestural handling of paint in Hick’s picture and probably that of the large and almost monochrome picture that hangs next to it, Stanislaw Ostoja-Kotkowski’s Form in landscape (1956), whose title confirms that it, too, is conceived as a kind of abstract landscape. Ostoja-Kotkowski was from Poland; also in the same room are three paintings by another Polish artist, Wladyslaw Dutkiewicz, who seems to be flailing about in search of a style. The earliest work, Calligraphy (c. 1952), is on the cover of the exhibition booklet, an abstract painting with a second abstract linear pattern – the “calligraphy” – drawn over it. Three years later, he has adopted a looser, semi-gestural style to return to landscape.

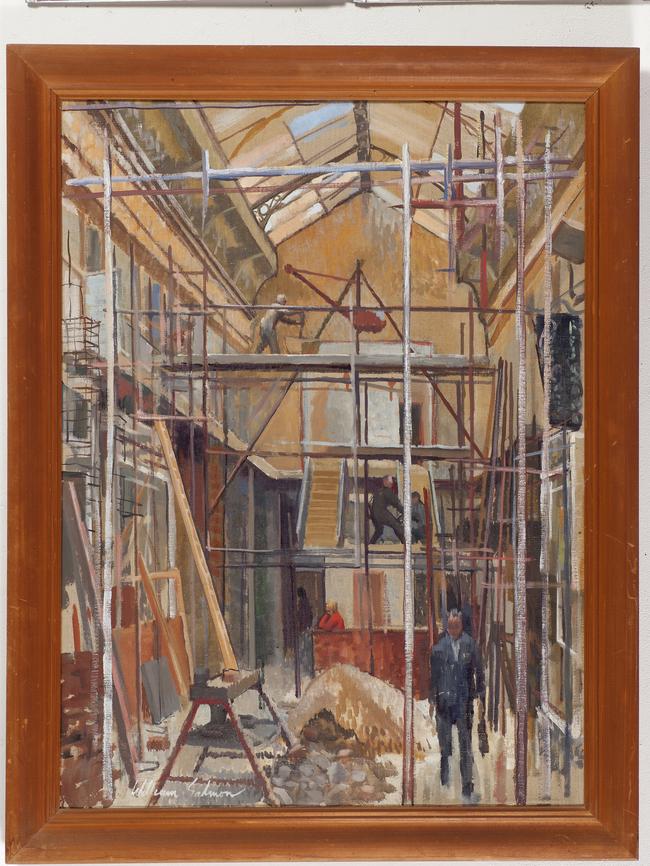

What is really striking about most of these works, with the partial and perhaps unexpected exception of the more conservative, such as William Salmon’s Reconstruction Gay’s Arcade (c. 1955), is how much of-their-time they are. Or to put it less kindly, they are fundamentally dated; they look like their time, but unlike Drysdale and other stronger artists, they do not transcend it and live on into other periods. And this is still truer of the hard-edge abstract paintings upstairs, which have aged less well, partly because it is such a sterile style and so completely disconnected from the Australian environment and experience. The optical works retain a certain quaint period charm, but they appeal to us more as visual games than as art of any consequence.

This strange and fatal sense of datedness is like what happens with forgeries, even the best ones. They look like the works they imitate, but they also look like their own time; and they get away with it at first because the elements that look their own time are invisible to their contemporaries.

To later viewers, on the other hand, they become more and more flagrant. Nineteenth century forgeries now look at us with the plangent sentimentality of the Victorian era, inconceivable in earlier centuries. To Van Meegeren’s contemporaries, his forgeries looked like Vermeer; to us, they look like paintings of the 1930s and little if anything in them escapes the sepulchre of the past.

Adelaide Mid-Century Moderns: Émigrés, mavericks and progressives Carrick Hill, Adelaide Until October 15

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout