It’s worse when you enter the exhibition itself. The first space in particular is over-designed with gratuitous partitions and details of paintings blown up to a scale at which their original aesthetic qualities are obliterated. The rest of the exhibition has been expensively fitted out to evoke domestic interiors, while the walls are papered in patterns drawn from the artist’s work. We might as well already be in the shop, where departing visitors are invited to buy merchandise decorated with what once were paintings.

This confusion is consistent with a general tendency at the NGV, over the last few years, to treat art and design as equivalent in interest, and to present fashion as though it were art. The Gallery seems to have aligned itself with the commercial ideology of “creativity” which allows advertising and other exploitative consumer industries to be equated with artistic forms whose ultimate aspiration should be truth; but it also reflects the debasement of much contemporary art to a product that is in reality barely distinguishable from those of the fashion industry.

The over-designed environment is also clearly an attempt to transform an exhibition of paintings into something like the “immersive” experiences that are increasingly popular today. We have seen egregious examples of populist installations based on massively over-scaled projections of paintings by van Gogh or by Aboriginal artists in recent years – the latter at the National Museum in Canberra, whose new natural history gallery is itself an immersive swamp of amorphous impressions punctuated by kitsch messages.

This approach to exhibition design is based on the assumption that audiences, even for a serious exhibition at the leading museum in Australia, are increasingly passive; they must be surrounded with an inescapable “experience” that they can absorb like a bath because they cannot be trusted to enter into the individual paintings and look and understand them. Fortunately for those willing to look more carefully and patiently, the pictures are also accompanied by generally excellent wall labels.

Some justification for the design in this case might be alleged in the aesthetic views of the Nabis themselves, who believed that art should extend to interior design. But in reality this commitment to design is more useful in understanding the aesthetic within their paintings: we see this most clearly in those of Edouard Vuillard, also represented in this exhibition, where figures tend to merge into their domestic backgrounds, like chameleons assuming protective covering. Perhaps the most disturbing implication of the design of this exhibition, however, is that Bonnard’s paintings are somehow unable to stand on their own merits without this bright decorative environment. And this in turn is probably a consequence of trying to present an appealing but second-ranking modernist painter as though he were an epoch-making master.

Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947) was a talented and intelligent young man from a good family, and he went to one of the best schools in Paris, the Lycee Louis-le-Grand, next to the Sorbonne (formerly the celebrated Jesuit College de Clermont, astutely renamed to flatter Louis XIV). He studied law to please his father, but soon began to work as an artist in the fin-de-siecle world of Paris in the 1890s.

Early paintings reveal his interest in the crowds of Paris and the fleeting encounters with anonymous passers-by already evoked in the poems of Charles Baudelaire. One such picture, The Cab horse (c. 1895) has a woman in the foreground reduced to a dark silhouette, yet the focus of the composition, like one of Baudelaire’s briefly-glimpsed beauties.

This love of flat silhouettes, often dominating the foreground, ultimately derives from Japanese ukiyoe prints, but had already been adopted by Toulouse-Lautrec and others. Lautrec’s influence is particularly striking in Bonnard’s poster for La Revue Blanche (1894), and a similar grouping appears on his decorative screen of Nannies’ promenade (1895).

Another aspect of the Japanese aesthetic that Bonnard adopted was a fondness for the juxtaposition of organic and geometric patterns, which we can already see in The Checkered blouse (1892); these red and white checks will recur in later years as the “toile de Vichy” tablecloths that appear in his numerous still life paintings, forming a grid-like background pattern to the objects set out on the tabletop.

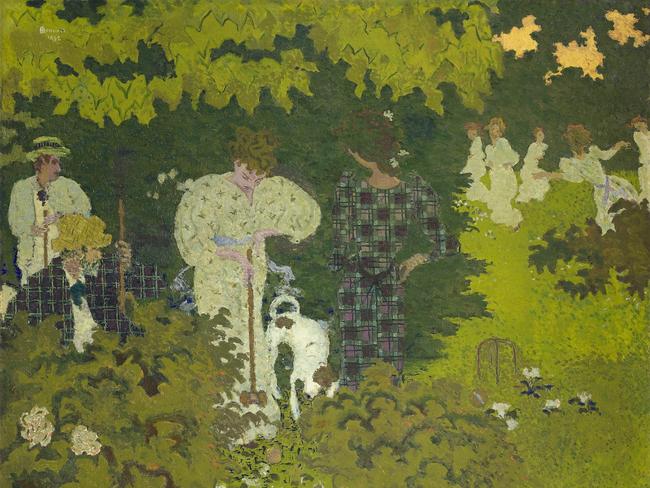

A similar formal play appears even more self-consciously in the much bigger Twilight, or The Croquet game (1892), in which the checkered patterns of his father’s jacket and the dress of one of the young women playing croquet are deliberately painted flat as though pieces of the fabric had been collaged onto the painting surface, in contrast to the soft and organic forms of the greenery that surrounds them.

This picture seems in many respects closer than any other in the exhibition to the style of his friend Vuillard, and yet it also reveals the difference between the sensibility and vision of each. Vuillard’s form of intimism is epitomised in a picture like After the meal (1893), an example of that chameleon-like absorption that I already mentioned of the figure into the ground: the implication seems to be that the individual is in some sense merely an expression of his social and even material environment.

The figures are a little more distinct but the impression much the same in the larger Family lunch (1899), in which the figures, separately occupied in their own activities after the end of the meal, are completely contained and enveloped within the world of artificial forms – wallpaper and tablecloth patterns, picture frames, vases and furniture – that surrounds them. The picture label, correctly citing Dutch 17th-century interiors as an inspiration, uses the word “claustrophobic”, but one might also think of “containment” or even “cocooning”.

Bonnard is quite different, in part because he does not evoke interiors of the same formal and cultural density, but also because he rarely paints groups of figures or a family in his mature work. This was perhaps partly because he led a relatively nomadic existence between several residences before spending the last two decades of his life in his house above Cannes, but also because he did not really have a family.

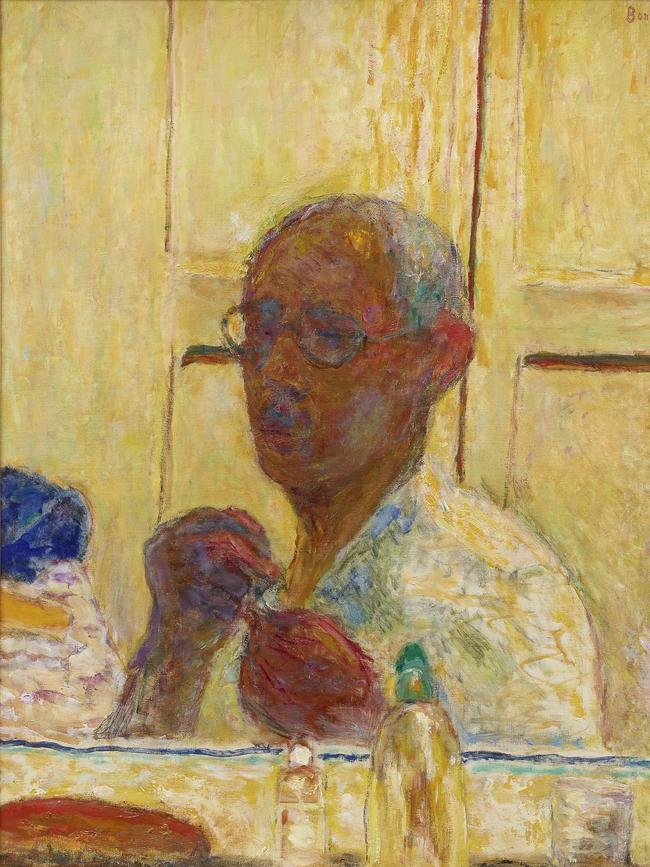

There are a number of mysterious things about Bonnard’s mature life, including the fact that he lived through the unimaginable turmoil of two world wars without particularly seeming to register what was going on. But another is undoubtedly his relationship with his mistress Marthe, whom he eventually married in 1925, but with whom he had no children. As his life progresses, he seems to become an increasingly elusive character, almost an insubstantial one.

Marthe herself was an elusive individual too, but also a controversial one, disliked by his family and friends and said to have played a part in his increasingly reclusive life in later years. She was born Maria Boursin (1869-1942) and Bonnard met her in a shop where she made silk flowers, but she adopted the name Marthe de Meligny, and is regularly but rather unfortunately referred to as “De Meligny” in the labels.

In fact, a name with the particle “de” in French is an aristocratic one, and the only working-class girls who took on such fake-noble names were courtesans. It was thus not a respectable name – like wearing cheap but ostentatious costume jewellery – and as we can see, she was known as “Madame Bonnard” from a very early date.

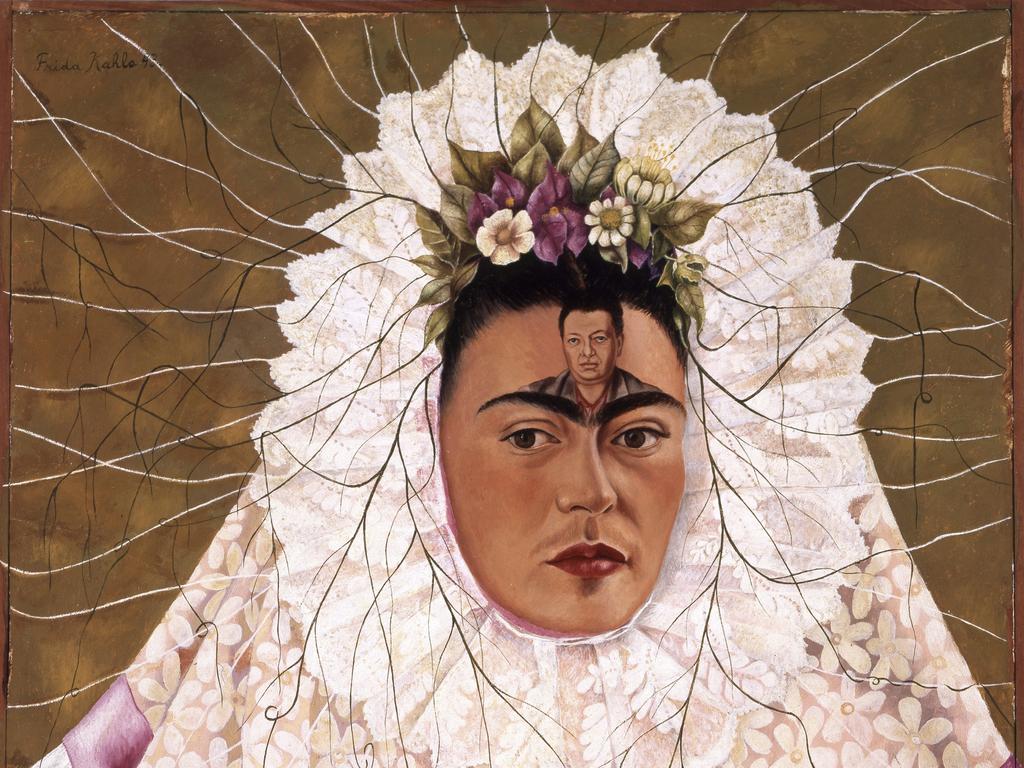

There is an early portrait of Marthe by Vuillard (1907) and an even earlier portrait of her drinking absinthe by Bonnard himself (1894) shortly after they met in 1893. This and another portrait of her in a larger painting, In a boat (1907) are among the only pictures in which we see her eyes. In the first of these she seems sly, but may just be drunk; in the second she looks more mysterious and seductive, although in Vuillard’s painting it is clear she is no great beauty.

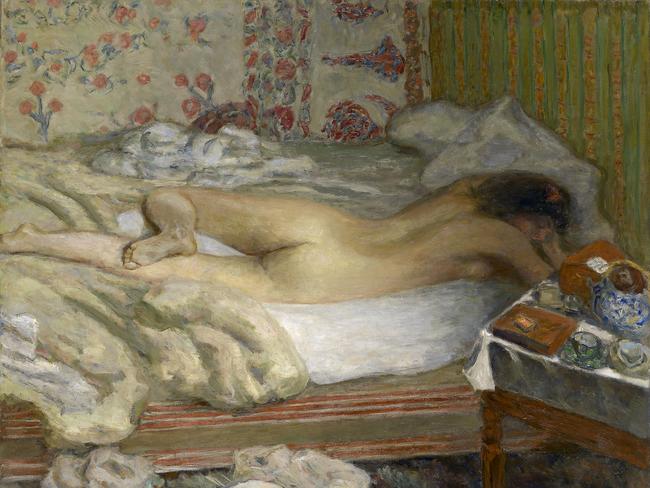

Bonnard took some photographs of her posing naked around 1900, and at around the age of 30, she still has a slim and almost adolescent figure; this is indeed how she appears in all the nudes that Bonnard painted of her in subsequent years, and art historians have wondered whether she did indeed remain eternally youthful in later decades – as she appears, for example in Marthe a sa toilette (1919) – or whether Bonnard was painting a kind of ideal from memory.

If he always saw Marthe through some ideal lens of memory, it was not purely as a result of tenderness and intimacy, for in fact Bonnard had affairs with a couple of other women, of whom the most important was Renee Monchaty. When, in 1925, Marthe seems to have forced Bonnard to marry her, perhaps because of her declining health, Renee committed suicide, so the last decades of the artist’s life, and his relationship with his wife – here the word claustrophobic seems apt – were inevitably shadowed by this terrible event.

These events help to explain the peculiar mood of Bonnard’s many interiors with tabletops, checked cloths, a variety of still-life objects, and Marthe, frequently accompanied by one of their pet dogs. These are undoubtedly images of domesticity and familiarity – in fact the painter is quoted as saying that he hated to paint objects that were not familiar – but they are not necessarily pictures of warmth or intimacy.

We can also reflect on the many interiors looking out into a garden, or onto the view at Le Cannet. These are perspectives onto openness, but from within enclosure; glimpses of life and freedom, but from within an environment that is comfortable indeed, but also perhaps constrained. They are not images of a longing for escape so much as the contemplation of freedom from within a self-chosen life of enclosure and security.

Above all, they are a witness to a life that has become completely consumed in the art of painting. It is as though, for Bonnard, painting was both his escape from and his accommodation to the realities of his existence. Whatever happened to him was less important than the daily act of finding balance and resolution in a painted composition.

There is a touching story attached to his last painting, clearly executed with great difficulty in the last months of his life; days before he died, he had his nephew bring it to him in bed so that he could make a final correction to the colour of the ground. Even in the face of extinction, painting offered the promise of transcendence.

Pierre Bonnard

National Gallery of Victoria, until October 8

Pierre Bonnard

National Gallery of Victoria, until October 8

Even before visiting this exhibition, we are struck by the anomaly of its title: “Bonnard designed by India Mahdavi”. There is no doubt that exhibition design is important, but like service in a restaurant it should be effective, attentive and discreet; its greatest virtue is in being self-effacing. Why does a gallery give such prominence to a designer, even if she is a celebrity designer to the rich?