Frida and Diego: Love and Revolution exhibition a success in Adelaide

There’s nothing worth seeing at the Art Gallery of NSW this winter, but many smaller galleries have done far better.

Over the past couple of years, it has become increasingly evident that there are serious problems with Australia’s galleries and museums, no doubt reflecting a deeper malaise in our culture, anxieties about our history and uncertainties about our national purpose and direction. These problems are apparent to anyone who takes the trouble to pay attention.

A few weeks ago Elizabeth Fortescue raised important questions in the Australian Financial Review: why is it that while the National Gallery of Victoria and the Art Gallery of South Australia have significant winter exhibitions, there is nothing worth seeing at the Art Gallery of NSW – coming down from the sugar-hit of its function centre extension?

In the case of the AGNSW, there has not been an exhibition of any importance since Matisse at the end of 2021, and the next one will be Kandinsky in November this year. Two years between exhibitions is a long time for what is meant to be one of our premier institutions. Many smaller galleries and museums, both in our big cities and in regional cities, have done far better; meanwhile the AGNSW has had the Archibald – which is the opposite of an intelligently curated exhibition – and The National, which is not an exhibition at all, but which might be seen as a promotional and gatekeeping mechanism used by the official art establishment to advance the careers of its favourites.

A real exhibition needs a focus beyond what the contemporary art promoters decide is cool. Exhibitions can be monographic, or based on a period, a movement, a style, a medium, a theme; but it is only this sense of what is in common that helps viewers understand what is also different and significant. And as I have observed before, our larger institutions should be generating focus exhibitions from each of their principal collecting areas every year.

The situation at the National Gallery in Canberra has been depressing for some years, but a low point was reached with the commission of a gigantic piece of outdoor sculpture designed by Lindy Lee and fabricated overseas, for over 14 million dollars. This was a ludicrous price for the quality of the work, and also represents a staggering opportunity cost when we think of what this sum of money could have bought for the collection – dozens of substantial paintings or sculptures, and hundreds or even thousands of works on paper.

Meanwhile the NGA also fell into the trap of backing the APYACC, just before the scandal broke that some of its surprisingly abundant production may have been made with the help of white assistants. The report commissioned by the NGA itself has, not unexpectedly, attempted to deny any wrongdoing, but only by dint of implicitly admitting the involvement of white assistants and justifying it on the basis that the artists signing the works retained “creative control”. However one looks at it, this has been a ghastly humiliation for the gallery.

The biggest exhibitions in Australia at the moment are Rembrandt and Bonnard, both at the NGV. The first of these was reviewed here last week, and I will discuss the second in a few weeks. The most important Australian art exhibition is not at an art gallery but at the State Library of NSW, a small but outstanding survey of the draughtsman and lithographer Charles Rodius, famous for his portraits of important colonial figures in Sydney in the second quarter of the 19th century, as well as Aboriginal men and women, to whom he devotes equal care and attention. This too will be reviewed in the next few weeks.

The other important exhibition, at the Art Gallery of South Australia, is devoted to Frida Kahlo and comes from the Gelman Collection in Mexico City. Some of these works were shown in 2016 at the AGNSW, in a rather thin exhibition filled out with photographic and documentary material. This one is more extensive and more satisfying in that it conveys a much better sense of the work of Frida’s husband Diego Rivera, who was considerably more famous than she was, and a leading international figure of the time.

Diego’s most important work was in the form of colossal murals with life-size figures and cannot be transported for exhibition, but a couple of these are photographically reproduced and occupy whole walls in the exhibition. Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Park (1946-47), seems to be set in the late 19th or early 20th century in the time of Porfirio Diaz, the leader who modernised Mexico and unlike most Mexican leaders of a century ago, survived to enjoy a comfortable retirement. The mural seems to represent a bustling Sunday crowd in Mexico City, but closer inspection reveals many little vignettes of social or ethnic tension.

Another mural, Detroit Industry (1932-33) represents the Ford car factory in that city, the biggest in the world. The celebration of industry is reminiscent of Dziga Vertov’s evocation of relentless movement and industrial dynamism in his film Man with a Movie Camera (1929).

It is particularly in contrast to Rivera’s functional but effective style and social realist themes that one can appreciate the specific qualities of Frida Kahlo, who is perhaps the most interesting overrated artist of the 20th century. Interesting because the work is often piquant, eccentric and memorable, but overrated because she never really transcends a certain narcissistic fascination with her own life, history and identity, and consequently hardly ever paints anything of consequence apart from self-portraits. In this regard she is like those immature novelists who cannot write about anything except themselves.

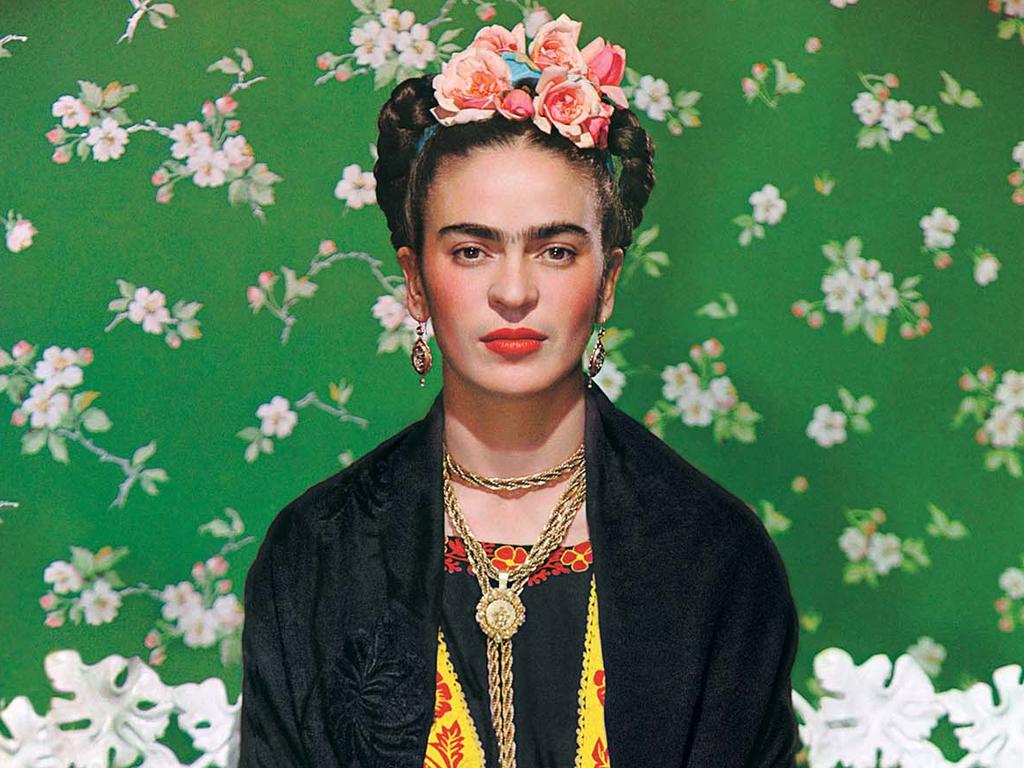

Kahlo was fascinated, of course, by her own background, which was an exotic mixture of Austro-Hungarian and German and, she believed, Jewish, on her father’s side, and Spanish and Indigenous Mexican on her mother’s. She paints herself at various times in ways that allude to these different strands in her makeup, but although she belonged to the well-to-do and educated urban middle class – and was much closer to her father than to her mother – preferred both in life and in art to wear colourful Mexican peasant dress.

This was no doubt inspired by nationalist sentiment as well as communist sympathies. At the same time the peasant culture of Mexico was a distinctive blend of Spanish settler and Indigenous elements, woven together over the 500 years since the Spanish conquest. And the Mexican Revolution, beginning in 1911 and followed by a couple of decades of bloody civil war, deliberately promoted the concept of the mestizo – the individual of mixed Spanish and Indigenous ancestry – as the quintessential Mexican.

So Frida’s choice of dress was both a political and a style statement, and the bright peasant colours made her stand out from all the other more conventionally dressed women around her. In fact, as the many photographs in this exhibition show, she was as concerned to perform a certain persona and identity as to paint herself in a distinctive way, and clearly encouraged and promoted her own role as an art celebrity.

What gives all these self-portraits a greater human depth is her story of physical suffering, beginning with polio in childhood, and then above all a trolley-car accident when she was 18, in which she sustained a series of terrible fractures, including to her spine, and in which a metal handrail pierced her abdomen. She eventually recovered but was left with recurrent pain for the rest of her life; in one of her most famous paintings, not in this collection, she represents herself naked from the waist up, wearing a brace, and with her torso opened to reveal a broken Ionic column in place of her spine.

Her injuries also seem to have made her incapable of bearing children. She became pregnant in 1932, soon after her marriage to Diego Rivera, but suffered a miscarriage which is the subject of a couple of lithographs in the exhibition. She subsequently had several more miscarriages and therapeutic abortions during the course of her short life; she died in 1954 at 47 after a series of unsuccessful operations to repair her spine. Many of these incidents in her life are also illustrated in photographs in the exhibition.

Her relationship with Diego was intense but difficult; they were married in 1929, separated in 1937, divorced in 1939 and remarried in 1940. Each had relationships outside the marriage but the most dramatic was Diego’s affair with Frida’s younger sister Cristina (represented here in a portrait by Diego from 1934), which provoked the original separation; but even this crisis was followed by a resolution after which the three somehow lived together. Not surprisingly, then, Diego also appears in a number of Frida’s paintings, beginning here with the pair of his portrait (1937) and a relatively straightforward self-portrait (1933).

Later self-portraits are more complex, like Self-portrait on Bed (1937), with its grim evocation of childlessness, Self-portrait with Braid (1941), Self-portrait with Red and Gold Dress (1941), and Self-portrait with Monkeys (1943), with its poignant echo of portraits such as Sir Joshua Reynolds’s Lady Cockburn and her Three Eldest Sons (1773) in which young mothers – sometimes represented as allegories of love – are surrounded by their offspring.

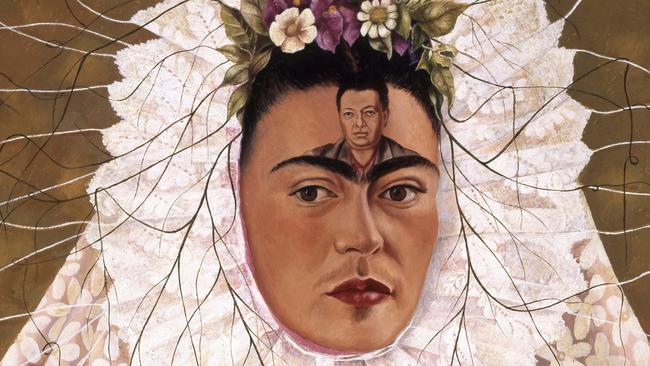

Most complex are the self-portraits that include Diego. In Diego on my Mind (1943), subtitled Self-portrait as Tehuana, Frida represents herself in the traditional costume of the women of the Tehuantepec isthmus, her face turned into a flower by an elaborate lace headdress, with a portrait of Diego painted on her forehead. The Love Embrace of the Universe (1949) sets her and Diego at the centre of a cosmic drama in which the universe, divided into light and dark, night and day, embraces the earth, which in turn seems to be divided into life and death, sleep and waking.

The earth, its nipple dripping with the milk of motherhood, holds Frida in her arms and she, finally, bears the naked Diego on her lap like an image of the Pieta. She weeps and bleeds, he holds fire or the divine vajra in his right hand and has the third eye of spiritual awakening in the middle of his forehead, for he had been a member of a Rosicrucian mystical order since 1926; thus Frida imagines herself as part of a cosmic system of life in which she is destined to be the mother of Diego and to nurture her husband’s enlightened vision.

Frida and Diego: Love and Revolution

Art Gallery of South Australia to 17 September

Frida and Diego: love and revolution

Art Gallery of South Australia to 17 September

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout