Images from a pre-digital past: famous photos re-created

This 40-year survey of work by Anne Zahalka raises questions about truth in photography.

When photography was invented in the late 1830s, it was the culmination of almost five centuries of interest in recording and rationalising the world of visual phenomena. Painters and scientists alike developed optical theories and systems of perspective, and the practical device of the camera obscura, known since antiquity, was refined with the addition of a lens in the Renaissance. The only element still required to make a photographic camera was a light-sensitive surface capable of registering the image that came through the lens, and that was achieved with the progress in chemistry of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

The fascination of photography for pioneers of the process such as Thomas Wedgwood at the end of the 18th century and later Louis Daguerre, Henry Fox Talbot and others, was the possibility of registering a direct imprint of the world without the intervention of the human hand. The photographic image thus came with an axiomatic presumption of truth; but the subsequent history of the medium has shown how artfully that truth can be shaped or modified: from selecting the moment of shooting to choosing the best image from a contact sheet, as well as choices of aperture and lighting, the use of filters, enlarging and darkroom processes.

In the 20th century, photography was increasingly exploited for the purposes of propaganda and manipulation, first by totalitarian regimes and then by corporations seeking to sell their products. Pictures of starlets were airbrushed to remove flaws and create an illusion of glamour. But such manual processes were soon made obsolete by the rise of the digital image, and today a whole generation has grown up in a world in which photographic images are associated with deception and falsification rather than truth.

The result is that many photographic artists in recent decades – from Bill Henson to Jeff Wall, Gregory Crewdson or Thomas Demand – have deliberately approached their art as a form of fiction. And fiction, as the Greeks well knew, could also be, albeit indirectly, a vehicle for truth. Anne Zahalka, too, was an early exponent of this new approach, but long before the digital image, and when all staging and editing had to be done manually.

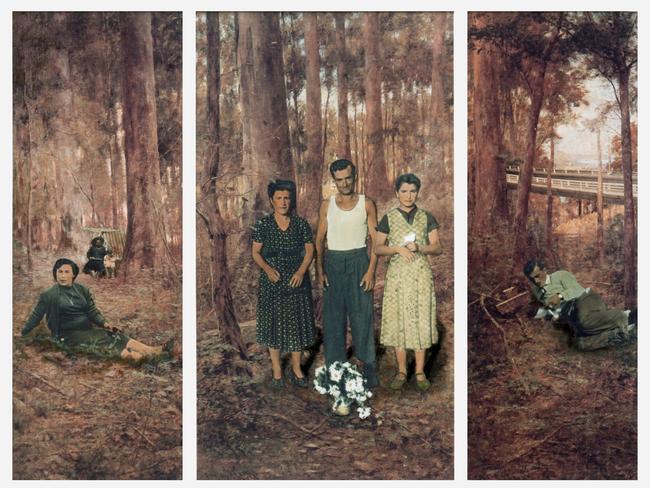

Her earliest notable work in this survey is the series The Landscape Re-presented (1983-95), in which she reproduces and alters a couple of well-known paintings by Frederick McCubbin. Thus in The Immigrants #2 (1983) she has taken McCubbin’s famous triptych The Pioneer (1904), which is at once a summation of and a farewell to the Heidelberg movement, replacing his figures with photographs of her own family, including her Czech Catholic father and Austrian Jewish mother, whose mother was killed in the Holocaust.

The wall label here rather confusingly describes another adaptation of McCubbin’s triptych, not the one on display. But more misleadingly still, it falls into the same cliches that too often take the place of thought in art writing: Zahalka’s work is said to “subvert colonial and historical metanarratives”, “challenge dominant representations” and “interrogate identity and explore notions of belonging and displacement’’. In discussing her 1982 variation on McCubbin’s Down on His Luck (1889), we read that “Zahalka’s satire critiques the colonising of landscape through white settlement and the clearing of land for urbanisation”. All of this implies a reductionist reading of works that are in reality more complex and subtle. Zahalka’s immigrant family are not replacing triumphant colonialists in the triptych, but in fact an earlier group of poor immigrants.

McCubbin’s Down on His Luck has nothing whatsoever to do with “the colonising of landscape” or the “clearing of land”; the figure in the painting is an impoverished and unemployed rural worker.

In 1987, Zahalka was awarded a residency at the Kunstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin and had an opportunity to reconnect more intimately with her European origins. It was also a chance to become more closely acquainted with the great tradition of early modern European painting, of which the museums in Berlin have such fine collections – West Berlin, as it then was, since the Wall did not come down until 1989.

This experience led to one of her most important and intriguing sets of work, shown under the collective title Resemblance (1987) for the work done in Berlin and then Resemblance II (1989) for a second set produced on her return to Australia. The premise of both series was to set up complex interior scenes in emulation of Vermeer and other Dutch and Flemish painters from the 15th to the 17th centuries. As in Vermeer’s own paintings The Wine Glass (Berlin, c. 1658-60), Woman with a Pearl Necklace (Berlin, c. 1662-64), The Astronomer (Louvre, c. 1668) or The Geographer (Frankfurt, c. 1668-69), the scenes usually involve one figure or sometimes two, and an interior environment filled with items relating to their profession or occupation.

One of the simple

st but most striking is the artist’s self-portrait, sitting at a handsome table resting on a Persian rug, with a catalogue of old masters no doubt from the Gemaeldegalerie before her, and a reproduction of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Dutch Proverbs (1559), another painting in the Berlin collection. On the table before her are various memento mori items familiar from Dutch still lives: an hourglass that has run out and an extinguished candle, as well as a pair of scales hinting at the Last Judgment. On the left is a camera, a reminder of her craft in a work that otherwise emphasises the importance of painting as a source of inspiration.

Another picture uses the same table, but this time with a tiled floor, which was painstakingly made of painted boards in those days before easy digital shortcuts. The tiles are consistent with the bucket in the background and the title, The Cleaner; the sitter is Maryanne Redpath, a New Zealander Zahalka met in Berlin who was then a performance artist and has more recently worked for the Berlin Film Festival. In the background is a reproduction of another Berlin painting, Hans Holbein’s portrait of the merchant Georg Gisze (1532), drawing our attention to difference between the two poses.

There is a curtain on the left of this composition, alluding to the foreground repoussoir devices used by Vermeer and others, but such elements are developed in the slightly later series made on her return to Australia. Most effective in this regard is The Card player, a portrait of her mother playing patience. The table is covered with a Persian rug, both an allusion to Vermeer and to her mother’s love of Oriental carpets which reminded her of the sophisticated and prosperous life her family had once led in Vienna.

The word “Shalom” on the letter holder is a recollection of her Jewish heritage, while the view into a hallway and a room beyond is a common effect in Dutch interiors. On the wall behind her is a print of McCubbin’s Down on His Luck, with the figure of the swagman painted out.

This is also, of all the photographs in the series, the one that most achieves a painterly quality of atmosphere; the pictures in Berlin were already beautifully lit, including their emulation of Vermeer’s subtle variations in the lighting of the background wall, but it is harder to achieve his sense of atmospheric density in photography.

Zahalka’s other well-known and – as we see from a display of book and magazine covers – endlessly reproduced series is The Sunbathers (1989). The largest picture in this series is the elaborately staged The Bathers, which is a re-enactment, so to speak, of Charles Meere’s Australian Beach Pattern (1940). The original painting is itself something of a phenomenon: although the work of a talented but relatively minor painter whose only other well-known work is Atalanta’s eclipse, for which he won the Sulman Prize in 1938, it has become one of the famous images of modern Australia, and a favourite with visitors to the AGNSW.

Meere’s painting is discussed at some length in an interesting article by Philip McCouat which can easily be found online (search for “The Origins of an Australian icon: Charles Meere’s Australian beach pattern”) and which I recommend, even though he quotes something rather simplistic that I wrote about this picture in 1997: McCouat cites several other scholars who have looked carefully at the picture and who draw our attention to the way it echoes both Michelangelo in The Battle of Cascina (1504) and Géricault in The Raft of the Medusa (1819). The article incidentally has much of interest to say about the first work directly inspired by Meere’s composition, Australian Beach Scene (1940) by his pupil Freda Robertshaw.

In any event, Zahalka’s version of the celebrated image is adjusted to reflect the greater ethnic diversity of Australia after half a century of post-war migration, but its greatest interest is perhaps again in what it makes us perceive about the difference between painting and photography: Meere can get away with a world turned into almost abstract modernist pattern, but photographed figures are stuck in a kind of stubborn reality – or at least they were before digital filters and editing could make them look as smooth and lithe as those of Meere. And yet even if Zahalka’s figures are not as athletic as those of her model, they are all slim; the invasion of junk food and the consequent epidemic of obesity has all taken place in the past three or four decades, coinciding with the revolution in information technology, personal computing and now the hand-held devices that have deluged our world in mendacious imagery.

The question of truth in photography – whether evoked through the fictional play of the Resemblance series or the questions raised in the process of appropriation in The Sunbathers, or indeed in the pseudo-documentary mode of the Hotel Suite Series (2008) – has never been far from Zahalka’s mind, but it seems to have become even more urgent, or perhaps direct, since the death of her mother in 2016. This event has brought her, if anything, closer to the drama of her mother’s life and to the fate of her grandmother, especially as she has sorted through and studied papers and letters that document these now vanished lives.

Perhaps the most moving part of the exhibition is thus the series of works titled The Fate of Things (2017-18). Here the pictures are mostly found and presented in archival form. There are poignant vestiges of past time, such as the locks of the artist’s golden hair cut when she was an infant. But most affecting is an installation of letters written in German, in a beautiful and refined hand, to her mother by her grandmother, before she was taken away to the concentration camp. The direct contact with the words and hand of one who disappeared so long ago is as vital as any image.

Geelong Gallery Collection

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout