Review: Misty Mountain, Shining Moon: Japanese Landscape Envisioned Art Gallery of South Australia

Japan has some of the world’s most modern cities, yet its heart still belongs to the countryside and to the mountains.

Landscape is a genre of painting that speaks of the relation of humanity to the world we inhabit: nature, the living environment, being itself, however we conceive of that ultimate ontological reality. That is why landscape, of all forms of painting, is the most open to a sense of transcendence and spiritual experience. But how does the painter achieve this? Those who haven’t given the matter much thought assume that landscape painters look for a good view, set up their easel and copy what they see.

Anyone who has ever tried to paint will realise at once that this is a fallacy: there is no such thing as copying, both because what is before your eyes is not a finite object but a phenomenon in whose very existence the observer is implicated, and because there is no direct equivalence between visual phenomena and the artificial form of a picture.

In reality, even before a particular view, painters will see different things, prioritise different things and most importantly transform them into artefacts with their own formal coherence within a particular style and vision: a romantic painter and an impressionist can look at the same view and produce quite distinct images of it. Even painters working in very similar manners, at the same time, before the same motif, will see or select different elements of the view, as we can see for example in the two pictures of Coogee Beach painted in 1888 by Tom Roberts and Charles Conder.

But landscape painters are not always looking at a particular view; in fact the habit of painting in oils directly from a natural motif only goes back to the late 18th century in Europe, first as a painting exercise or as a study for a work to be completed in the studio, and then increasingly, with the Barbizon School and then the Impressionists, as a way of making finished exhibition pictures.

Before this time, the normal way to paint landscapes was to make sketches from nature, including, as we can see in the many surviving drawings of Claude Lorrain, detailed studies of the morphology of trees, and ink drawings of particular sites or light effects, which were then composed into finished paintings in the studio. The advantage of this method was that the landscapes were imbued with a deep understanding of natural forms and appearances, but remained poetic and imaginative creations, not to say formal inventions such as those of a musical composer.

In Europe, this was the basis of the classical style in landscape painting, but there were many variants within that tradition, as well as alternative traditions, notably that of the Dutch in the 17th century. The epicentre of the classical tradition was Rome at that time, dominated by the different manners of Claude and Poussin; and yet although the classical landscape often alluded to the environment of Rome and the Campagna, it was universal and almost abstract in spirit rather than local.

The Dutch on the other hand, after they finally threw off their Spanish rulers and achieved independence in the early 17th century, became intensely interested in their own national landscape.

There was nothing abstract or universal about the compositions of Van Goyen or Salomon van Ruysdael, with their low horizons, vast expanses of water, moody skies and above all their views of particular Dutch cities; the same is true in the next generation with Ruysdael’s nephew Jacob van Ruisdael (who preferred this spelling), with his windmills or the bleaching fields at Haarlem.

There is a similar dichotomy between a more classical and universal landscape tradition and a more local and national one in Japanese art, as we can see in the current exhibition at the Art Gallery of South Australia. The contrast is in fact even more striking here because the two traditions are also represented by different media: ink painting, the medium of the Chinese scholar painter and the modern, popular woodblock printing.

In fact the reality is a little more complex again, for there is also another older Japanese decorative painting tradition, represented here by folding screens with landscapes and birds, often against a gold background. This tradition, dominated by the Kano school, assimilates Chinese influences but converts them into a distinctively Japanese aesthetic, which has something in common with the flat decorative painting of the Heian period (794-1185). A fine example of the Kano school is Kano Sanraku’s six-panel screen Birds and flowers of the four seasons (c. 1619-35).

The painters of the Kano school and others like them were highly trained and expert at their craft. In the Chinese tradition such professional artists were held in much lower regard than the gentleman scholar, who was by definition an amateur. The scholar painters’ education and culture were primarily literary, but the materials they employed in painting – spurning the colours of the professional artists – were the same as those used for writing, brush and black ink.

The pictographic nature of Chinese characters, moreover, allowed for a kind of continuum between writing and painting that is inconceivable in alphabetical languages. Thus writing itself becomes painterly in calligraphy, achieving a kind of expressiveness that is inaccessible in alphabetical languages where calligraphy, even at its height in Persian nasta’liq script, remains essentially decorative. Conversely, painting becomes writerly, one might say, and Chinese artists developed a language of visual forms to capture the spirit of rocks, water, bamboo or pine trees.

Eventually, and late in the history of Chinese classical painting, a famous manual was published introducing artists to this visual language. The Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden appeared in China in 1679, printed in five volumes in colour. It was soon available as a printed woodblock volume in Japan, too, and was especially useful to Japanese painters during the long isolation of the Edo period; there is a copy, printed c. 1813, in the exhibition.

There are several examples of scholar painting in the exhibition, too, but the one in which it is easiest to admire the traditional elements of the genre is Yasuda Rozan’s Mountains and water (c. 1875). Characteristically, it is a view of high wooded mountains with falling water and a river in the foreground; the format goes back to the Sung and Yuan dynasties in China, in the 12th and 13th centuries, and is deeply informed by Taoist ideas of nature – the yang of rocks, the yin of water; mist as the breath of mountains – which no doubt resonated with Japanese Shinto sentiments.

The human element is always present in these compositions, but man is small and insignificant in comparison to nature. Little figures walk up paths or cross bridges; there is usually a scholar’s retreat where he can read, drink tea and commune with the great life of nature that surrounds him. The Chinese model of the gentleman scholar artist however was based on the scholar intellectual class who ran the imperial civil service, while the greatest Japanese exponents of classic ink painting (sumi-e) were Zen monks, from around the 15th century.

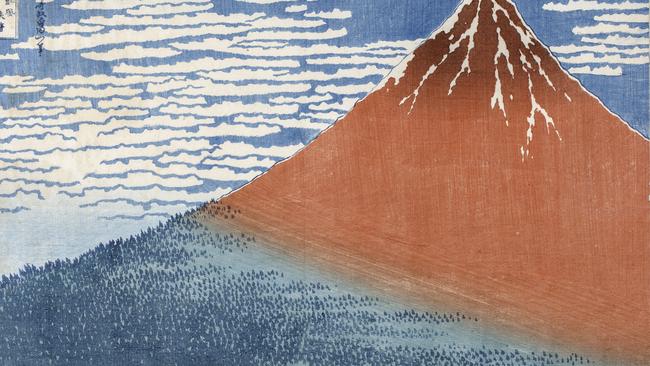

We are reminded, in contrast, of the Japanese interest in specific national landscape sites at the very beginning of the exhibition, which opens with a number of images of Mt Fuji, with its perfect conical form and snow-covered peak which has been admired for centuries and often dominates the background of landscapes, anchoring the whole composition. One of these images is by Hokusai, from his celebrated series of Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji (c. 1830-32). A couple of recently-acquired photographs, one from 1885-95 and the other from 1920 attest to the continued fascination with the sacred mountain, in each case including a viewing figure seen from the back.

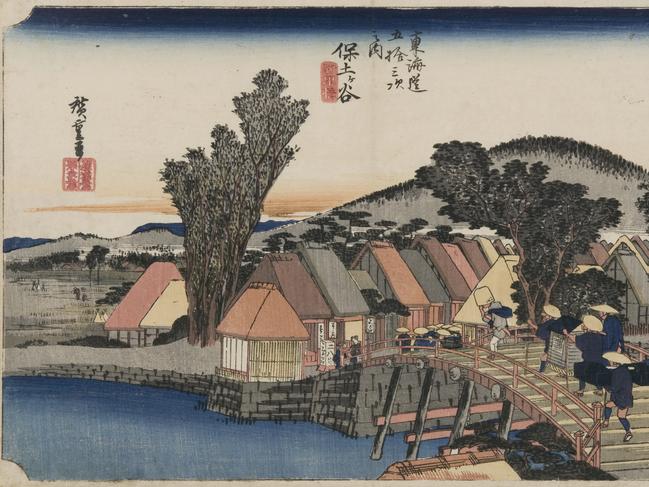

Other famous images of Mt Fuji are by one of the greatest masters of Japanese woodblock prints, Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858). In 1832, Hiroshige made the journey from Edo (Tokyo) to Kyoto, along the famous Tokaido Road. This road had been used for centuries but constructed in its modern form in the 17th century, with 53 stations where accommodation and refreshments and other services were available to travellers. It was these stations that provided the title and the structure for Hiroshige’s series: Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido Road (1833-34).

Hiroshige’s love of the picturesque landscapes at every point of the journey is matched by his fascination for the detail of human occupations and activity along the way, and he has a genius for harmonising these distinct elements through composition. Thus in one print he follows a group of mounted and walking travellers as they cross a causeway across a lake and, for the only time on the journey, discover Mt Fuji on their left.

In another he evokes a wonderful sense of movement in a group of porters, with their round straw travelling hats, lugging a kago (passenger litter) across a bridge. His clear flat colours and even the arbitrary but decorative differentiation of the colours of the thatch roofs in the background later inspired the art of Hergé, the creator of Tintin.

In contrast, another print offers us an aerial view of travellers fording a river with the help of specialist porters. The government at the time deliberately restricted the building of bridges as a security measure to protect the capital against rebellious armies, so crossings had to be made at natural fords and with assistance.

After the Meiji Restoration in 1868 and with Japan’s rapid modernisation, railways soon made the Tokaido Road obsolete as a practical means of travel and many of the inns at the roadside stations lost their custom. But the famous sites remained in the hearts of the Japanese and a century ago a couple of artists decided to replicate Hiroshige’s journey, even if by then it had already become a sentimental one.

Otani Sonyu and Iguchi Kashu travelled the famous road in 1919 from Kyoto to Tokyo, and in 1922 they produced their own Fifty-three Stations in eight horizontal scrolls, printed in monochrome collotype and then coloured with woodblocks.

The first scene shows Nihonbashi Bridge at night, in the centre of a modern Tokyo, with an electric tram and modern office buildings, their windows all similarly illuminated by the new electric lighting. Interestingly though, this first scene remains in black and white except, significantly, for the pale yellow in the windows, and colour begins to come into the work as we leave the city for the country.

Even though this work does not succeed in distilling the journey into anything like Hiroshige’s intensely memorable and beautifully constructed images – indeed the artists seem to be seeking a sense of flow rather than a series of vignettes – it does hint at something that remains true of Japan today: that it is an extraordinarily modern, urbanised, technologically sophisticated society, yet preserves its soul in the countryside and the mountains, rooted in the landscape.

Misty Mountain, Shining Moon: Japanese Landscape Envisioned, Art Gallery of South Australia, until November 12.

Misty Mountain, Shining Moon:

Japanese Landscape Envisioned

Art Gallery of South Australia, until November 12

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout