Why Australia was the great muse for newly arrived artists

The new experience that Australia offered, both in the earliest days and throughout the colonial period, led to a curious phenomenon.

Graphic Investigation – prints by postwar émigré artists in Australia

Geelong Art Gallery to October 15

Artists have been coming to Australia from the beginning of settlement, and indeed were especially important in the first half-century of Australia’s modern history, before the advent of photography changed the whole way we think about images, introducing a new dichotomy between mechanical and utilitarian pictures that could be reproduced as multiples and imaginative, expressive and unique fine art paintings on the other. Early artists played a vital role in documenting the new land, but from the early days of exploration to the first decades of settlement in Sydney, there was a continuum between utilitarian and aesthetic ends.

The difference between John Glover and Conrad Martens, although they worked only a short time apart, illustrates the change brought about by the new technology. Glover, who was 64 on the day of his arrival in Hobart in 1831, belonged decisively to the pre-photographic age even though the new technology was well established by the time of his death in 1849. Martens, who had acted as a documentary artist with Charles Darwin on the Beagle in 1833 and 1834 and arrived in Sydney in 1835, was painting from the 1840s until his death in 1878 in the new world of the photograph.

Both, however, responded attentively and imaginatively to the new environment and conditions of Australia. Contrary in fact to the most persistent myth of Australian art history, the colonial painters who preceded Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton were close observers of the new and unfamiliar landscape and flora of Australia; even more remarkable is how quickly they became attuned to the communities in which they found themselves and began to articulate their feelings of displacement and resettlement.

The new experience that Australia offered, both in the earliest days and throughout the colonial period, led to a curious phenomenon: that the artists who came here, not only from England but from many parts of Europe, tended to become better and more original than they had been at home. It was not just a matter of being big fish in a small pond, but of finding themselves in a new environment and responding to its demands and opportunities. This can certainly be said of Glover, Martens, Von Guerard and Buvelot, among others.

It may seem surprising, especially at first sight, that the same thing did not happen with artists who came to Australia in the 20th century. No foreign artist became a leading figure in Australia, nor did any of them bring a new style that had a decisive influence on the direction of local art; Australian artists certainly imitated international trends, especially in the postwar period when we seemed to become increasingly unsure of ourselves and anxious to imitate American fashions, but they were not brought here by leading metropolitan figures. Although there were influential exhibitions of foreign work, notably the Herald Exhibition of French and British contemporary art (1939) and Two Decades of American Painting (1967), the artists themselves did not settle in Australia.

This is a particularly striking fact when we consider the interesting group of Central European émigré artists who are the subject of a survey at Geelong – another exhibition drawn from the Colin Holden print collection, following the collection Sydney and Melbourne printmakers discussed earlier this year.

No doubt the reason that did not have a greater impact here is partly because Australia already had, around the mid-century, a strong group of distinctive artistic personalities, such as Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker, Russell Drysdale and Arthur Boyd. But it may also have been because, unlike their predecessors a century earlier, these individuals really did bring European styles with them which they did not significantly adapt in response to the new natural and social environment. Those styles, moreover, could not match the forceful and articulate images produced by local modernists who had maintained strong roots in the figurative traditions of painting.

They did, however, have a significant influence within the fields of printmaking and, as we shall see, of education. Henry Salkauskas and Eva Kubbos founded the Sydney Printmakers Group in 1961 and Udo Sellbach, with Tate Adams, Grahame King and the great NGV curator Ursula Hoff, established the Print Council of Australia in 1966.

It may seem odd that it took new arrivals to set up these institutions, especially when we consider that the previous Colin Holden exhibition was devoted to Australian printmaking between the wars. But in fact Australia’s golden age of printmaking, which began in the Edwardian period and flourished in the 1920s and into the 1930s, ran out of steam around the end of the decade, coinciding with the death of some of its principal exponents: John Shirlow in 1936, Ethel Spowers in 1947, Sydney Ure Smith in 1949, and finally Lionel Lindsay in 1961, coincidentally the year of the foundation of the Sydney Printmakers Group. Australian printmaking was thus a medium waiting to be revived by a new generation.

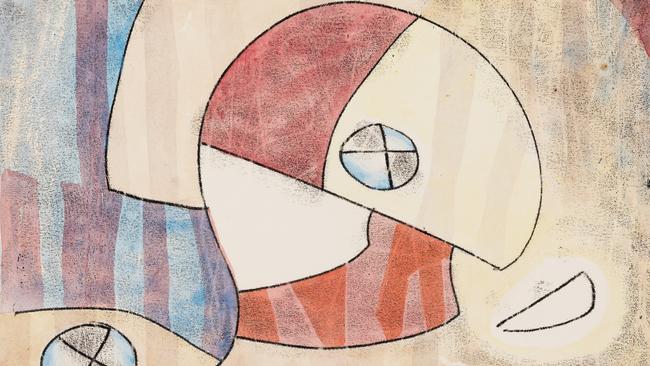

The first artist in the group, and also the first in the display, is Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack (1893-1965), who had been at the Bauhaus in Weimar but left Germany for England in 1936, in the face of the rise of Nazism. In 1940 he was deported to Australia on the Dunera as an enemy alien, and spent some time in an internment camp at Hay in NSW and later in Victoria. One of his most memorable works, unfortunately not in this exhibition, is a poignant woodcut titled Desolation (1941). He was released from detention in 1942, thanks to the headmaster of Geelong Grammar, where he became art master until his retirement in 1957. He is represented in the exhibition by four whimsical monotypes, two of which are hand-coloured, reminiscent of the style of his friend Paul Klee.

Next is Henry Salkauskas (1925-79), born in Lithuania, which was successively subjected to Russian occupation, then German and then Russian again. In Australia, with his mother, who was a doctor – his father had been killed in a Russian concentration camp – he worked first in a stone quarry and later as a house painter, all the while producing austere black-and-white linocuts, two of which are exhibited here: the more intriguing of the two is made up of rows of signs that recall some kind of writing system, densely packed but thinning out as though stammering towards silence in the lower middle of the composition. Salkauskas’ friend and fellow Lithuanian Eva Kubbos (born 1928) is represented by coloured linocuts, notably Shifting from dark to light (1962), printed from two blocks and a couple of other pieces printed from four blocks – one for the black and three for the additional colours.

Tate Adams (1922-2018) was Irish rather than Central European; he was a printmaker, but also ran Crossley Gallery in Melbourne and, with George Baldessin (1939-78), established the Crossley Print Workshop in 1973, printing and editioning the work of Roger Kemp, John Olsen, Albert Tucker and others. Baldessin, born in Venice and arriving in Australia in 1949, is also included in this exhibition, but although perhaps the most prominent and today best-known figure in the collection, does not belong to the same cultural background shared by most of the others.

Among these is Hertha Kluge-Pott, who was born in Germany in 1934 and who is represented here by a couple of works from 1961 in which simple animal motifs are turned into dense, stylised and suggestive images by the combination of strong drypoint for the linear component and aquatint for tone. Aquatint is also used, this time in conjunction with etching, by another German migrant, Udo Sellbach (1927-2008). Sellbach’s work uses the human figure to express a postwar existentialist sense of moral drama, but he was most influential as a teacher, including at RMIT, the Tasmanian School of Art and especially as the founding director of the Canberra School of Art (1977-85).

It was there that Sellbach employed the man who was the most interesting of all these artists, if still little-known, elusive, and also most famous as a teacher. Petr Herel (1943-2022) was born in Czechoslovakia but like so many of the men and women in this exhibition was a cosmopolitan and polyglot; he studied in Prague and then in Paris, and after his initial visit to Australia he taught at the Ecole Nationale des Beaux-Arts of Dijon before joining the Canberra School of Art where he founded and directed the famous Graphic Investigation workshop (1978-97), with a focus on producing artists’ books. It is Herel’s workshop that has given this exhibition its title.

These books were produced on hand-made paper, illustrated with prints and set in letterpress by skilled typesetters. A number of artists’ books are displayed in cabinets in the centre of the room: one of these is from the time of the workshop, with illustrations by Sellbach. Three others, with illustrations by Herel, belong to subsequent years: I, I am a blind man, three poems by Jorge Luis Borges (1975) in 1999, Jean Tardieu’s The Truth about monsters (mid-20th c.) in 2007, and Aloysius Bertrand’s Gaspard de la nuit (1842) in 2008.

The texts are usually poems or other modernist literary texts with a cult following among connoisseurs, especially those with a taste for surrealism. Another etching by Herel, from 1965, during his years in Prague, is based on such a work: Lautréamont’s Chants de Maldoror (1868-69). His most impressive print dates from the first year of Graphic Investigation; Moon-noon (1978), and shows why, for all the enigmatic quality of Herel’s imagery, he was ideally suited to direct a workshop on artists’ books.

His style represents the survival of surrealism in Central European countries like Czechoslovakia and Poland after the war, when the movement’s influence had ebbed, if not collapsed in France. No doubt the style, with its wilful ambiguity and even obscurity, offered a space of expressive freedom in these cultures over which the Iron Curtain had fallen. At the same time, as we can see in Herel’s style, surrealism is deeply inflected by a much older northern European tradition of the fantastic: Brueghel and Bosch are clearly the deepest inspirations, combined with recollections both of modernists like de Chirico and even of the antique – as here the crouching northern figure, representing the world of night, is contrasted with one who strides into the sun, wearing a Greek tragic mask.

These works are intriguing and poetic in their own right, but they also offer some idea of the spirit of Herel’s teaching in Canberra: it was in many ways radically unconventional and not at all focused on the market or the production of saleable commodities. But unlike the painting department at the same period – with its large, heavy-handed canvases – Graphic Investigation was profoundly imbued with a sense of history and memory, and perhaps above all with an axiomatic belief in the value of skill, technical mastery and care.

Graphic Investigation – prints by postwar émigré artists in Australia

Geelong Art Gallery to October 15

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout