The story of Impressionism is well-known. But is it true?

Art critic Sebastian Smee argues the Impressionist movement rosefrom a year of terror rather than a reaction against a rigid culture.

Look at a list of the most-visited art exhibitions in any year, and some familiar names will inevitably appear: Monet, Manet, Renoir, Degas, Sisley, Pissarro, Morisot. As arguably the first modern art movement, Impressionism continues to captivate contemporary audiences, and our interest in it shows no sign of dissipating: just a few weeks ago, on November 18 , one of Claude Monet’s paintings of water lilies sold at auction at Sotheby’s New York for a staggering $US65.5m ($100.7m).

The story of Impressionism, then, is well-known. In 1860s Paris, the Academie des Beaux-Arts maintained a stranglehold on the display of art through its annual Salon. Through this exhibition the Academie promoted a conservative style of painting: figurative, idealised, and privileging the painting of scenes from history of mythology.

In 1863, following the rejection of over 4000 works from the annual Salon by members of the Academie’s jury, a “Salon des Refuses” was established to showcase those works deemed “inadequate” by the academicians. This exhibition proved more popular than the official Salon, and opened the public’s eyes to emerging tendencies in painting.

While the Salon des Refuses proved short-lived, the group of young painters rejected by the Academie would form their own society, and host an exhibition in the studio of the photographer Nadar in Paris in 1874. Among the works on display in that exhibition was a painting by Claude Monet, depicting the port at Le Havre, Monet’s home town. Entitled Impression, Sunrise, the work would lend its name to the broader movement and group of painters who are now household names.

Impressionism, then, was a backlash against the stuffiness and strictness of academic painting. Embracing new technologies like the metal paint tube that allowed them to paint outside en plein air; and rethinking the place of painting in society given the invention of photography that could capture a perfect likeness of a subject, a group of young, ambitious artists formulated a new visual language.

Or so we thought.

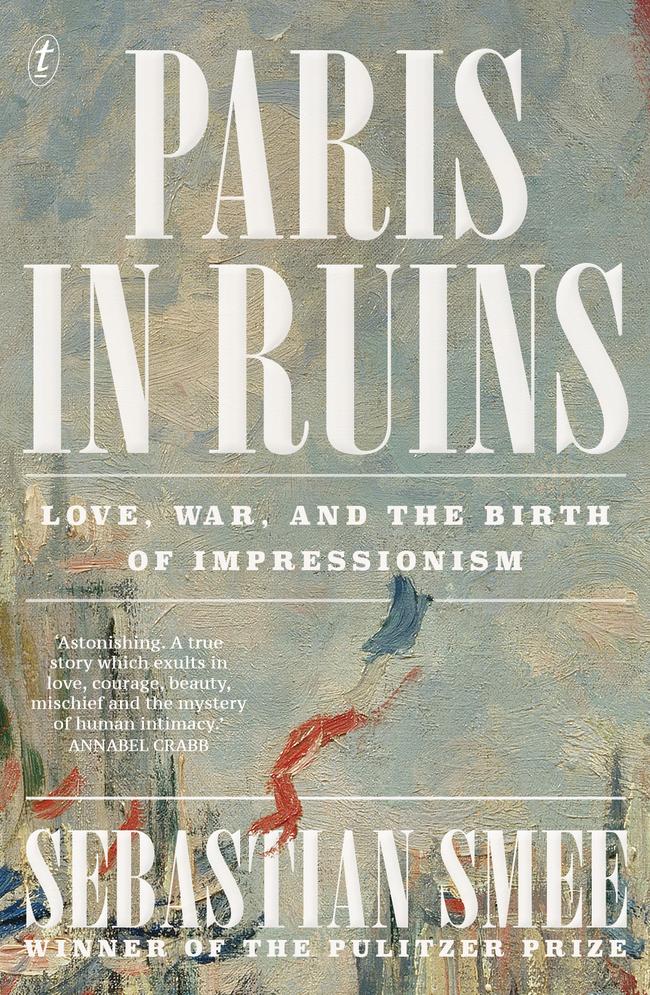

Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic Sebastian Smee’s latest book, Paris in Ruins, offers a new perspective on the birth of Impressionism.

Smee’s tale also starts with Nadar, though not in 1874 at the photographic studio in Paris that hosted the first exhibition of Impression as we might expect. Instead, we are in October 1870, when we find Nadar launching two hot air balloons from a hill in the north of Paris. Nadar had previously flown in a hot-air balloon to take the world’s first aerial photograph. But his mission this time was quite different. One of the balloons carried Leon Gambetta, the Republican politician and future Prime Minister of France, while the other was full of mail. The reason for this hot air balloon trip was to bypass the Prussian forces that were besieging Paris, leaving the capital’s residents so hungry they resorted to eating zoo animals to survive.

For Smee, missing in the canonical history of the Impressionists is a proper recognition of the impact of what the writer Victor Hugo termed l’annee terrible. The “terrible year” between 1870 and 1871 saw France go to war with the Kingdom of Prussia; depose its Emperor Napoleon III; have its capital city surrounded and bombarded for four months; and eventually resulted in a revolutionary government seizing control of Paris and establishing a Commune before being violently suppressed at a cost estimated at 20,000 lives.

This period of political turmoil saw countless artists flee Paris, although Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot and Edouard Manet remained behind. It is the latter two that Smee is most interested in. In his text’s introduction, the author describes the core of Paris in Ruins as being “an affair of the heart” between Manet and Morisot. In truth, the two often disappear in the narrative, taking a back seat to the political figures of the time as Smee vividly guides the reader through the chaos, upheaval and disorder of l’annee terrible. But that Manet and Morisot’s relationship extended beyond mere mentorship is clear.

Manet was already married, and Morisot would eventually marry Edouard’s brother, but the 12 portraits Manet produced of Morisot attest to their closeness. Repose, of 1871, is an alluring portrait of Morisot reclining on a sofa, while 1872’s Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets, painted just before Morisot married Manet’s brother, is a tender and delicately-executed likeness that betrays an undeniable intimacy (of exactly what sort we may never know) between the two artists.

Equally undeniable is the fact that the two painters emerged from l’annee terrible deeply changed. And this brings us back to Paris in Ruins’ central contention. In a chapter entitled The Launch of Impressionism, as the book reaches its conclusion, Smee explains that the movement’s subjects — its light-filled fields, Baron Hausmann’s bustling boulevards — represent a conscious rejection of the kind of “polarising political rhetoric” that had torn France apart in the years prior. As he writes of these paintings: “They offered respite not only from the traumas of recent events and the scars still marking Paris itself but more generally from the stress and insecurity of living at the beginning of the modern age.”

Having survived the military and civic catastrophes of 1870 to 1871, the question for the Impressionists now was how to respond to them. The answer was in those quickly-crafted, sketch-like renderings of a fleeting moment in time. As Smee suggests, it is hard not to see Impressionism’s emphasis on the ephemeral and the fugitive as an expression of a “heightened awareness of change and mortality”.

Impressionism, then, was not simply the rejection of some stuffy academicians you might read about in your undergraduate art history class. Developing out of one of the most chaotic periods in French history, the movement represented a rejection of violence, of war, and of destruction, instead embracing beauty, serenity and peace. As Sebastian Smee skilfully shows us, out of the darkness of l’annee terrible there emerged light.

Matthew J. Mason is an art historian based in Perth. He was previously Lecturer in Art Business at the Sotheby’s Institute of Art in London.