French Impressionism, National Gallery of Victoria

A new exhibition at Melbourne’s NGV sets out to have the viewer see the ravishing works of French Impressionism with new eyes.

ART has always been a window to the world. And never has that window been more needed, or more appreciated, than now, as our country’s borders remain closed and snap lockdowns continue to remind us how precarious is the freedom to enjoy our surroundings. So the arrival here of an exhibition of international artists could be seen as the first real step in reconnecting to the world outside our own borders. Or, to flip the proverb, since Australian’s can’t go to the mountain, we may as well bring the mountain to Australia.

In partnership with Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, Melbourne’s National Gallery of Victoria will be home to one of the largest exhibitions of French Impressionism to ever arrive in Australia. More than 100 works of art by the masters of the movement will be on display at the gallery from June 4.

While serendipitous isn’t quite the word for the impact COVID-19 has had on society or on the world at large, those responsible for the exhibition at both the NGV and the MFA might be inclined to apply it here, with Australia managing to make it through the worst of a pandemic and be socially prepped, for lack of a better term, to engage with and enjoy an exhibition of this import. “We’ve been working on this exhibition for several years,” explains Katie Hanson, curator of European paintings at MFA in Boston, who curated the artworks that will be on display. “If I had a crystal ball and had known about COVID, I’d be a very different person. [But] the timing of the exhibition was always for June of 2021.”

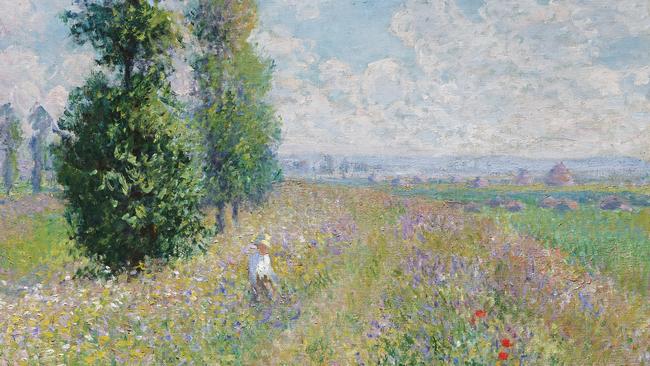

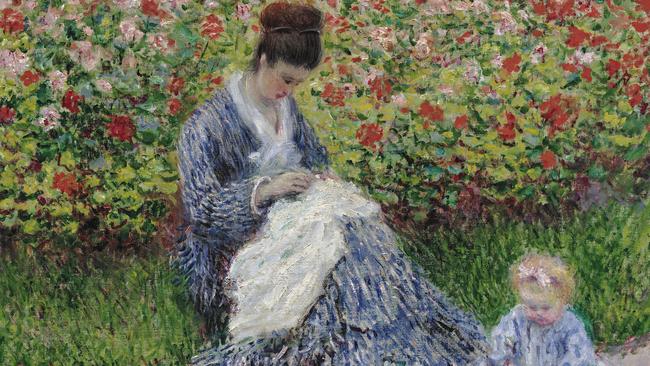

“[Australia has been] lucky, I think, that by the time the exhibition has come around we are in a situation where...we can travel in between states,” says Miranda Wallace, curator at the NGV who, along with colleague Ted Gott have been working with Hanson on the development and delivery of the exhibition. For Wallace and Gott, the artistic practices and philosophies of the Impressionists are seen as particularly pertinent to an Australian audience, reflecting the reconnection that many of us are having with our surroundings and the rediscovery of freedom in our own backyard. “Monet would go away for two to four weeks,” explains Gott. “He’d leave his wife and his partner and kids and he’d go into the French countryside, looking for landscape vistas to paint...That’s very much like Australians being unable to travel now and rediscovering Daylesford and the Wimmera and the Mallee.”

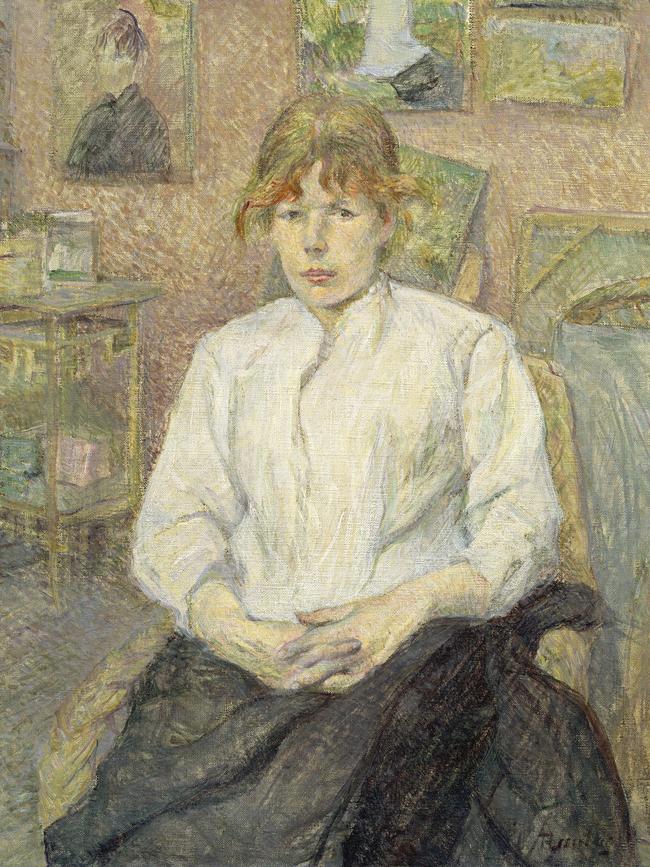

The collection brings to Australia works by some of the greatest artists ever to hold a brush. Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, maverick multitasker Camille Pissarro, and no less than 16 canvases by Claude Monet – arguably the most famous and widely known practitioner of Impressionism and its philosophical approach to exploring the surface and textures of the natural world’s beauty. Ranging from the group’s early days of experimentation learning from the Realism artists of the Barbizon School that informed the primary motif of painting en plein air, or outside, to the movement’s later incarnations of Neo-Impressionism, which pushed the light-focused exploration of the Impressionists to its limits.

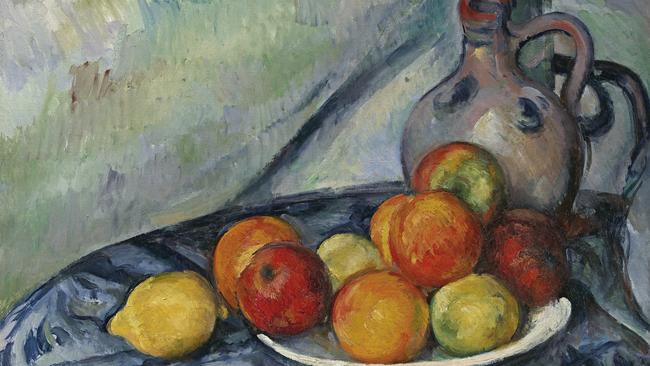

Also included in the exhibition will be several key works by the women of the Impressionist school, Berthe Morisot and the American Mary Cassatt. “It was very important to represent women artists and Mary Cassatt’s paintings are housed in the American department at the Museum of Fine Arts,” Hanson tells WISH. “I am the curator of European paintings, so I worked closely with the curator responsible for Mary Cassatt’s paintings to make sure she was represented in the exhibition. And we have one painting by Berthe Morisot in the MFA’s collection, and being able to have this beautiful installation of still life paintings that includes her still life was something that was also really important to me in organising the exhibition.”

Gott adds that giving women the opportunity to exhibit alongside them was one of the main tenets of the Impressionist movement. “They wanted the freedom to include women artists, which was incredibly revolutionary at that time. Because there were other art circles in Paris. They’re actually called circles – cercle d’art – but they were all male-only clubs.”

This rejection of tradition and radicalisation of cultural norms is an oft-forgotten aspect of the Impressionists, left behind in the wake of our affection for the beauty of blooming water lilies in a pond or the shifting facade of Notre-Dame in fog. While many of us are familiar with key aspects of Impressionist art – velvety colour palettes, brushstrokes of feathery quality that create dreamlike images where the edges flow into one another like reflections on water (a common inspiration among the Impressionists) and notions of “tranquillity” – Gott hopes that viewers will rediscover the raw energy and rebelliousness that underlined their work.

“[The theme of the Impressionists], I would say, is freedom,” he explains. “The desire to throw off previous constraints. Previous dictates to what others were supposed to do, what they were supposed to paint, how they were supposed to live, how they were supposed to present their work. They defied every expected convention of the day, and were determined just to create their own world, paint their own way, paint their own chosen subjects, frame their works in their own way, present them on walls of their own colour, and also just organise an exhibition movement itself.”

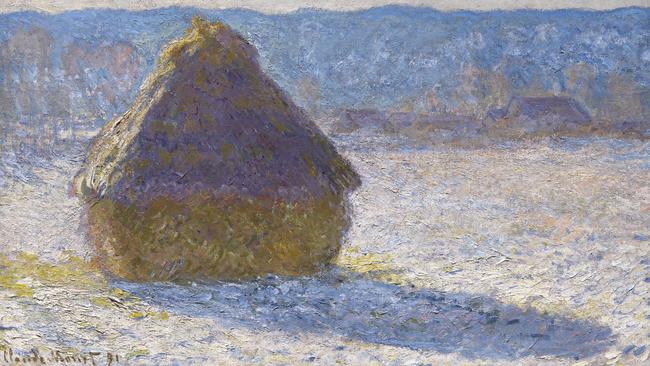

Of course, understanding how a painting of the French countryside might be thought radical requires a little mental time travel and context on how controlled the state-sponsored salons were when it came to what was considered “good art”. (The more things change the more they stay the same...) Arguably the first modern avant garde movement, the Impressionists broke with tradition in several senses. Rather than painting history, they painted the world around them (more than a few of the Impressionists, including Monet, had their roots in the Realism movement). They struggled with the conservative direction taken by the official École des Beaux-Arts, which dictated the themes and style art should take. As all good indie artists do, they rejected the mainstream exhibitions and competitions held to honour artists of the time. They remained, for all purposes and despite growing infamy and popularity, outsiders from the acceptable artistic scene. According to Hanson, it was viewing Monet’s Grain Stacks that gave Russian Expressionist and abstractionist Wassily Kandinsky the inspiration to let his own brushwork move across the canvas unfettered by tradition.

“[He] recounts this amazing story about going to an exhibition in Moscow and seeing Monet’s Grain Stack paintings, and he doesn’t recognise what that motif is,” explains Hanson. “It’s a funny structure if you’ve never seen it before, and he recounts feeling initially upset that a painter doesn’t have a right to be so indistinct. Then he sort of thinks through and recounts in his own words that he couldn’t stop thinking about these paintings. So clearly it didn’t matter what the motif was, it was the painting. It was the colours, it was the composition, and so to think that that’s part of his own story about his move toward abstraction, you wouldn’t expect that looking at a Monet grain stack, but then he tells you himself.”

Of course it’s no small poetic touch that one of the first major collections to show in Australia post-lockdown would be artworks that depict the world we live in so directly yet deliberately shift the perception of the spectator to reveal how beauty can be evinced in even the most banal of scenes, whether that’s a pile of grain or the continued reduction of the surface of buildings. Familiarity can often breed contempt and in this case it’s twofold: we’ve become so accustomed to the surface value of Impressionism and it’s visual prettiness that we lose sense of the ground-breaking methods the artists were employing in creating these artworks – the soft blurriness of the paintwork, the delightful colour palette, ranging from the vibrant hues used by Renoir to infamous pastels of Monet. Then, and most poignantly, it is the Impressionists’ primary motif that hits hardest – it’s all about the variety of life outside our front door.

During lockdown, parks and green spaces became focal points of neighbourhoods and filled with people who would normally be indoors. Emptied cities became labyrinths of new experiences as we embraced running and walking as methods of exploring, just to experience a taste of freedom as modern flâneurs. The familiar suddenly became new, and this was what the likes of Monet and Renoir began to explore. “[Impressionism was about] artists really looking at the world around them and portraying it in their own way,” says Hanson. “I know for my husband and myself, we’ve done more hiking in the past year. I live a stone’s throw from the Museum of Fine Arts, but we’ve been driving half an hour, an hour, away from here most every weekend to be in nature and to have bigger spaces and to see different things.”

Hanson says it’s important to remember, however that the Impressionists, weren’t just about painting idyllic scenes of landscape; they were an urban movement too, deeply embedded in the energy of the city or urban experience, as seen in the works of Degas or Renoir’s luminous depiction of public soirees. “Impressionism encompasses somebody like Degas, who most often portrayed Paris, its suburbs, and mostly its inhabitants... on through to Monet, who I think we think of as the exemplar of Impressionism now… [and] who was much more a landscape painter.”

While more familiar names such as Monet and Renoir may set the scene for most attendees, the inclusion of Camille Pissarro gives due credit to the man who it could be argued was the true progenitor of the Impressionist movement.

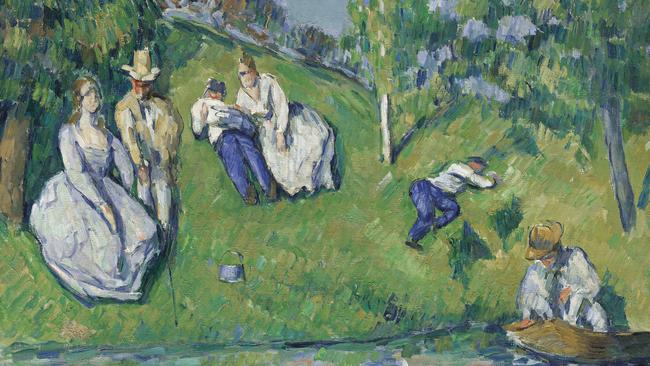

“[Pissarro is] such a fascinating, fascinating artist,” says Hanson. “He’s 10 years older than Monet. He’s four years older than Degas. He grew up in the Caribbean in St. Thomas, so he has Danish citizenship. He doesn’t even have French citizenship, which is always an important thing to keep in mind when a period of political upheaval, which is one they lived through, and yet he’s someone who is at the heart of this movement. I mean, he exhibits in all eight of the independent exhibitions that they co-organised. He is someone who is sought out by other artists for advice in life and in art. Cézanne paints with him. Gauguin paints with him. He’s also one who is, because he’s so open to those around him, his vision is really clued into the humanity of the nature he sees.”

In choosing artworks from the massive catalogue of Impressionist pieces available, Hanson says she kept a primary philosophy in mind to help winnow them down to a cohesive narrative that would help keep the experience of the paintings fresh. “I was really interested in encouraging visitors to look closely at the works of art and to have the humanity of these artists in mind as they were looking,” she explains. “So the thought-pairing that underpinned the selection was vision and voice. I’m looking at things the artists said about themselves and their own struggles and achievements, and things that they said about one another. So there’s a moment in the exhibition where you see a Renoir still life next to a Diaz still life.”

In viewing the artworks, it can be easy to get lost in the moment and forget that the operation to get them into Australia is a work of art in itself. “It always is delicate, whether there’s a pandemic or not,” says Wallace. “People know in broad terms that these exhibitions travel usually on aeroplanes, and of course with flights greatly reduced there’s been a lot of work done... I guess there’s been a lot more scenario planning for all the different options for flights.”

For a start, the works of art will come in multiple shipments. Flight delays and even just bumping the art in favour of other shipments, which Wallace says can and does occur regularly, can mess with an already tight schedule: “Even before the pandemic, you could find that your shipment is bumped because there’s a plane full of seafood that gets priority because it’s considered more important! We still have couriers for shipments, we still have the same degree of security, it’s just a lot harder when you know that couriers have to go into quarantine; It’s a bit more of a process to make sure there’s always someone representing the institution, accompanying the art. And that’s proven possible, it’s just taken an enormous amount more organising.”

Gott explains that the crates themselves used to transport the pieces are themselves something of a work of art. “There are literally hundreds of people involved at both ends, at various custom points along the way. And of course the crates are incredible constructions,” he says. “As you know, they are many times larger than the paintings they contain and they are climate controlled, pilot proof. They’re shock proof, and they’re designed to keep out moisture, heat, insects, dust... everything. So they are themselves, highly complex pieces of engineering design. It’s an incredibly complex process, the entire thing.”

French Impressionism will show at the National Gallery of Victoria from June 4 until October 3, 2021

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout