These bursts of creativity by older artists are inspiring

These men and women – who’ve had the courage and focus and grit to live a richly creative life – are still creating, well into their eighties.

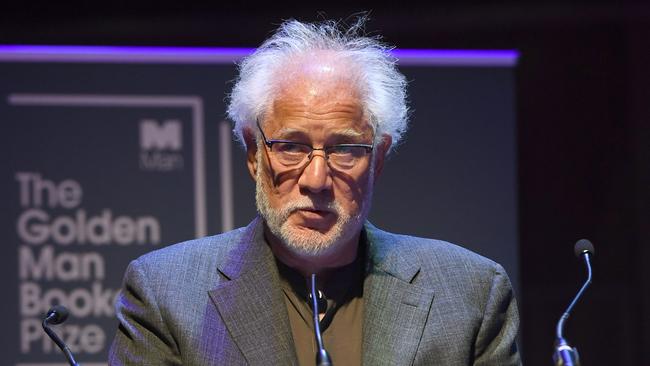

A new veering. To great artists, who have given us so much pleasure over so many years, and are now heading towards the end of their careers. Those men and women who’ve had the courage and focus and grit to live a richly creative life, and are still creating, well into their eighties. People whose work is luminous with beauty from a lifetime of observing, in wonder. I’ve just devoured Michael Ondaatje’s new book of poems, A Year of Last Things, and oh, the poignancy in that title. The writer, who has just turned 81, opens the book with this: “Reading the lines he loves/he slips them into a pocket/wishes to die with his clothes/full of torn-free stanzas/and the telephone numbers/of his children in far cities.”

The work is a distillation of recollections. Lovers, landscapes, friends, books. In one poem Ondaatje enfolds four etched-in-memory names of his mates from his 17th year, a tight posse of monikers never lost. As with all of us, surely, for we remember so strongly the sing-song rhythm of the names of kids closest to us from school days. Then he ventures back further, further, into primary school; to a teacher and a boy who became a character in a novel. “You swim into late afternoon. The past more distant/more alive.”

In this net of late, creative flowering I also scoop up Wim Wenders, whose most recent film is Perfect Days. One of the most profound I’ve ever seen. It’s centred on a Tokyo toilet cleaner in his sixties, a humble man who’s developed a way of being instructive to us all. The film is a masterwork of economy that says so much about a director nearing the end of his rich span of creativity. About what’s important and what isn’t in terms of family, work, class, stillness – and the singular ways we try to cleave to happiness in our later years.

By relinquishing complication, Wenders suggests. By succumbing to the quietness of routine, and simplicity, and the certainty of the known. And by taking pleasure in small things. A song on a cassette. A meal at a nook in a trainstation, night after night. A novel every evening before bed. And photos, carefully taken over many lunch hours, of light through leaves.

The film’s original Japanese title – Komorebi – means the light of the sun leaking through the trees; the dance of shade and light. Trauma, a complex past, family fracturing, all flicker at the edges of this toilet cleaner’s self-created life, yet his wry lightness of being contrasts with the angst and jitteriness of the mainly younger people around him. The film is infused with the gentle, unflashy wisdom of a grand master looking back, with confidence, and chuff, and a balming sense of peace.

At this year’s Adelaide Festival I moderated a session of celebration for Tom Keneally, which looked back at an extraordinary life and body of work. On stage was his editor, a writer mate and his daughter, and filmed inserts were played from people who’d had great influences on his life – a movie star, a priest. As stories and laughter and tears tumbled forth I thought, why don’t we do this more often at our festivals? Celebrate our great men and women of letters, and of celluloid, and the visual arts, as they enter the twilight of their lives? There’s so much accumulated wisdom there. So much joy, for us, and for them.

“They can see the finished map,” Michael Ondaatje writes in his new book, and it feels so true of these artists still blooming in the latter stages of their lives. There’s a transcendent lightness to their work, in the way that Lloyd Rees and Monet achieved a moving luminosity late, so late, in the span of their creativity. The fearlessness, the exultation and the purity of the beauty reminds me of choristers nearing the devastating time of their voices breaking, when their song is at its most heartbreakingly beautiful. And then that voice is gone.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout