Australian spy Dick Ellis‘ reputation as a traitor may have been wrong

He had been a legend of the Cold War spy game but after his death Dick Ellis’ reputation was trashed by Spycatcherauthor Peter Wright. Was he a man wronged?

The world of British secret agents before the 1970s conjures up images of double-decker buses, black cabs, Pall Mall gentlemen’s clubs, stale cigarette smoke, middle-aged men in bowler hats, red phone boxes, creaking floorboards, green desk lamps, manilla folders, clapped-out Trabants and East German border crossings manned by humourless communists in fur hats. It’s clichéd but true. Where did Colonel Charles Howard Ellis – Dick to most people who knew him – fit in to all of it? And, intriguingly for a man born half a world away in Sydney, without connections, without a silver spoon in his mouth, how did he get to the very top of the spy game?

One American newspaper called Ellis “Britain’s number-three spy at the end of World War II”. Brian Toohey and William Pinwill, co-authors of Oyster: The Story of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service, described him as “the most intriguing figure who has crossed the often-surprising landscape of Australian intelligence”. Sensationally, after his death in 1975 the ruddy-cheeked Ellis was publicly accused of being a traitor – a triple agent who in the 1960s had apparently secretly confessed to his treasonous crimes.

According to CIA historian Thomas F. Troy, Dick Ellis was “widely believed to have been both a Nazi and a Soviet agent”. British espionage journalist and author Chapman Pincher wrote in 1981 that Ellis had been the beneficiary of “the most blatant cover-up” and “broke down after interrogation in 1965 and confessed to having spied for Germany before and during the early stages of the war. This would have been a capital offence in wartime”. Pincher passed away in 2014, aged 100. He went to his deathbed maintaining Ellis was guilty, his case against the man an encapsulation of the old idiom that “there’s no smoke without fire”.

Ellis’s life appeared to be an incredible, untold tale; it was astonishing that no biographer before me had attempted to write a proper book on this enigmatic individual (Phillip Knightley, to his credit, tried to get a film made about Ellis but it never materialised). I found myself wondering whether, despite all the relentless smearing and character assassination from the Daily Mail to Newsweek to the Washington Post, there was another explanation for Ellis’s confession. Could he have made a false confession, professing guilt in order to protect someone else? What if he was actually innocent?

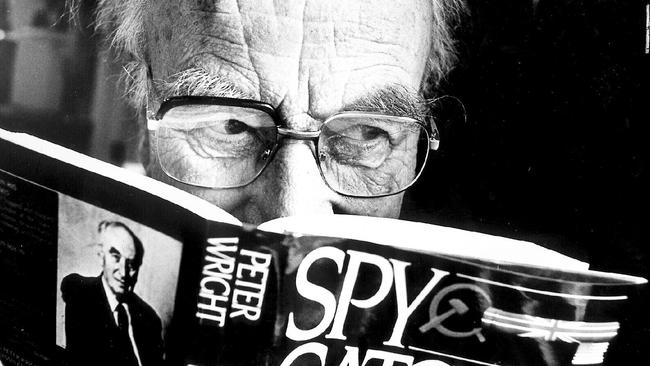

The late Peter Wright, who worked for Britain’s domestic intelligence agency MI5, was in the interrogation room with Ellis when he allegedly confessed; Wright became a confidential source for Pincher, and gave him the inside scoop he needed for his books demonising Ellis (1981’s Their Trade is Treachery and 1984’s Too Secret Too Long). On his own account Wright would author (with ghostwriter Paul Greengrass, who would go on to direct various movies in the Bourne spy action franchise) one of the best-selling books of the 1980s, Spycatcher, in which he laid out the circumstantial case against Ellis, whom he dismissively called “Dickie”. While some thought Wright’s knowledge was on an altogether different scale, not everyone was impressed with his modus operandi. “Behind the guarded doors of Leconfield House [the London headquarters of MI5], Peter Wright was behaving like a Witchfinder-General,” said one insider.

So, what if there was more to the story of Pincher and Wright themselves and their motivation to nail Ellis? And was Ellis really a traitor of epic proportions, or a hero? Four decades before the term even entered our lexicon, could he have been a posthumous victim of cancel culture, where truth doesn’t matter and an allegation is enough to condemn someone in the court of public opinion?

Peter Wright began his investigation into Dick Ellis as part of the joint MI5-MI6 Fluency Committee into Soviet penetration of Britain’s secret service. Wright, who died in 1995, aged 78, said he was looking for “definite clues” linking Ellis to the Soviets. Curious thing, a definite clue; sort of like an open marriage. What is it exactly, and how do you define it in terms everyone agrees on? A clue is always simply a clue but, in Wright’s case, a clue was just another word for his confirmation bias. He wanted Ellis’s blood on his hands.

Wright’s idea of “definite” was reading Les Nôtres: Vie et Mort d’un Agent Soviétique, the autobiography of Soviet spy Ignace Reiss’s widow Elisabeth Poretsky, in French. As Wright describes it in his 1987 book Spycatcher, he “seized on an extraordinary statement which had not appeared in the English edition. Poretsky said that in the late 1920s [Reiss] had an agent high up in British intelligence.”

So Wright “travelled to Paris in 1966 to see Mrs Poretsky” and “produced a spread of 20 photographs from my briefcase. Some were dummy photographs, others were of known colleagues of her husband, and one was of Ellis, dating from the mid-1920s. She picked out all those she ought to have known, and Ellis as well. “‘I do not know this man’s name,’ she told me, ‘but I am sure he is familiar’.”

The only problem is that Poretsky’s book was first published in French in 1969 – the same year that the English edition, titled Our Own People: A Memoir of Ignace Reiss and His Friends – was published in Britain and the US. So why would Wright be going to see Poretsky in 1966, three years before its publication?

Wright then went to Amsterdam to meet Bernie, the widow of former Soviet agent Henri “Han” Pieck. He writes of Bernie: “She too picked out Ellis’s photograph but refused to say why.” And then Wright had Stephen de Mowbray, an officer with Britain’s foreign intelligence agency MI6, visit the widow of Richard Sorge, who’d spied for the Soviet military intelligence agency GRU. “She recalled ... a meeting on a street corner in London. She and Rickie [Sorge] had gone together to meet this agent, but he had told her to stand well back and cover him in case there was trouble ... she had seen him, but not well. [The officer] showed her the photographs. ‘This man looks familiar,’ she said, ‘but I could not be certain, after over 40 years.’ It was Ellis’s photograph.”

So Ellis looked familiar to three women who were once married to Soviet agents who aren’t known to have had any contact with Ellis. Yet that was enough for Wright and the paranoid, witch-hunting Fluency Committee, which then hauled the retired septuagenarian Ellis into a gruelling interrogation over eight days with Wright and Major Theodore Xenophon Henry “Bunny” Pantcheff.

Wright and Pincher had a field day describing what happened next. “Ellis was summoned to an interview and he was challenged about the kind of information he might have given his former brother-in-law [Aleksei Zelensky],” wrote Nigel West in his 1983 book, MI6. “The investigator told Ellis that an Abwehr [the name for Nazi Germany’s military intelligence service] officer who had bought Zelensky’s information was willing to fly to London to identify ‘Captain Ellis’.”

Initially, Ellis denied the charge, West claimed, but on returning to Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) headquarters the next day for a second interrogation, he “admitted to selling the SIS order of battle [the organisation’s structure] to the Abwehr. When pressed about whether or not the Soviets had subsequently taken advantage of this lapse, Ellis insisted that he had never had any contact with the Russians. He also denied any further contact with the Abwehr after he’d left Paris for the last time.”

The investigators still harboured doubts as to the completeness of Ellis’s confession. Pincher writes in Traitors (1987) that “the interrogation was gradually made more hostile ... Ellis continued to profess his innocence with a stream of lies”, and in Their Trade is Treachery: “[Ellis] was confronted with the report of the German officer who named him as a spy. His response was that it must be a forgery. The interrogators threatened to bring the German officer over and confront Ellis with his evidence, and ended the session by giving Ellis 24 hours to ponder the consequences if that came to pass.”

Recalled Wright in Spycatcher: “Ellis denied everything for several days. He blustered and blamed the whole thing on jealous colleagues. But as we produced the evidence, the Abwehr officer’s report, he began to wilt ... after lunch on the Friday he returned to the interrogation room in the basement of the old War Office, known as Room 055, with a typed sheet of paper.” Wright described this as “a confession of sorts”, adding that Ellis admitted passing over detailed order-of-battle plans for British intelligence – information he knew was already being passed on to the enemy – as well as betraying a telephone tap between Hitler and his foreign minister Joachim Von Ribbentrop. Wright said Ellis admitted to last having contact with the enemy in December 1939, after the outbreak of war.

Ellis, said Pincher, had run into debt because his British pay was too low, and had borrowed money from Zelensky. His brother-in-law pressured him for information to sell to the Germans and Russians. He informed his interrogators he’d needed the money to pay for medical treatment for his wife. “So he had taken the easy way out, becoming more and more deeply compromised.”

Pincher asserted that Ellis had “betrayed the British intelligence achievement in tapping the Hitler-Ribbentrop telephone link”, fully aware that this information would end up being relayed to the Nazis. “He also admitted making use after the war began of a brother secret service officer to deliver secrets, unwittingly, in an envelope delivered to an agent, whom he knew to be working for the Germans, and to bring back a package containing money.”

Pincher also claimed that Ellis, aware that his interrogators had nothing on him during his time at British Security Co-ordination in New York, denied having continued to spy for Nazi Germany while in the US and Canada. “Nevertheless, his confession constituted unquestionably the worst case of British espionage to the Germans both before and during the war. When told that he had committed treason in war and could have justifiably been hanged, he broke down and pleaded physical frailty against any further cross-examination, but the interrogators were determined to continue their probing on the following day.”

According to Pincher, Ellis “continued to deny any secret dealings with the Russians” and insisted that the Petrov affair [the defection to Australia of Soviet diplomat and KGB officer Vladimir Petrov and his wife Evdokia, in 1954] hadn’t been the cause of his sudden dash to Britain from Australia.” Ellis had come back to the UK to marry, he told Pincher. Under pressure, he supplied a woman’s name. “Inquiries soon showed that she had already been happily married at the time and, though she had met Ellis, had never had any intention of marrying him. Ellis then pleaded that his memory must have been at fault and gave the name of another girl. This, too, proved to be a false trail.

“He denied that he had met [the disgraced British intelligence officer and Soviet double agent Kim] Philby on his return from Australia, which was known to be a lie, or that the secret service had warned him not to contact his former colleague. It was decided that, as a last throw, Ellis should be offered immunity … if he would confess his treacherous activities with Russia and name his contacts.”

As Pincher described it, Ellis “resolutely denied” being a double agent for the Russians yet Wright pressed Ellis on the all-important Soviet connection. “The next day we took him through the odd chain of events – his trip to Australia, and his rapid return to Britain, and the coincidence of Petrov’s defection. But he denied everything, even when he was caught out in repeated lying about his actions until he retired. Not even an authorised offer of immunity could make him change his mind. But I have little doubt of Ellis’s involvement with the Russians.”

Even Pincher admits, “There was no firm evidence against him, nor were there any witnesses.” But what did it matter? An accusation was enough. Ellis “was broken”.

Like Wright, Pincher didn’t know Ellis; nor did the three widows who’d apparently convinced Wright to haul Ellis in for an interrogation. One of Ellis’s staunchest defenders, Bill Ross-Smith, did know Ellis. In a letter to The Sydney Morning Herald on February 2, 1983, he maintained Ellis had never been on the radar of a molehunt. He even said no interrogation of Ellis had taken place, on the basis of Ellis having been so trusted as to be tasked with weeding top-secret files at MI6. He claimed Australia’s former external affairs minister Percy Spender agreed with him.

But today, in spy books found in bookshops and libraries all around the world, the narrative sticks. You’ll find it in books such as Unholy Trinity by Mark Aarons and John Loftus, who write: “Only a handful of people in British intelligence were told Ellis’s secret, and they decided that it was so shocking that neither the FBI nor the CIA should know.”

An impassioned defence of Ellis is mounted in two chapters of Canadian author William Stevenson’s 1983 book Intrepid’s Last Case. This latter account of Ellis was Stevenson’s sequel to 1976’s A Man Called Intrepid, a biography of Ellis’s former British Security Coordination (BSC) boss in the US, fellow Canadian William Stephenson, aka “Intrepid”. For that book, a huge hit around the world, Ellis had written the foreword, though he died before publication.

When I emailed Stevenson’s widow, Monika Stevenson, in 2022, she took the conspiratorial view on Dick Ellis and his fate. Her line of thinking was similar to that of William Stephenson, who’d told a journalist in 1983 that it would have been “child’s play” for Kim Philby or another unknown Soviet mole to set up Ellis.

“You probably know,” she wrote to me, “that the charge of double agent against Colonel Ellis originated at a time when the infamous Soviet spy Kim Philby set in place directives received from his Soviet bosses. Because of Philby’s high rank in SIS he had virtual carte blanche to carefully construct false messages, which were then leaked to the British communications system in order to deceive the decisionmaking elite and the public.

“From there, through a network of other Soviet spies – some of whom Philby himself had put in place – and others who were part of the larger web of double agents put in place by the Soviet Union, disinformation was also leaked to the US, Canada and many European countries.” One of the “most important” of these disinformation leaks, she claimed, was about Ellis.

Philby lived out his days in the Soviet Union as a hero, but British, American and other Western intelligence services didn’t know how many other Soviet moles had successfully infiltrated their ranks.

“I [was] part of conversations my husband had about this with Sir William Stephenson and others who were directly involved in tracking down other double agents who had been set in place under Philby’s tenure,” Monika Stevenson wrote. “No one in that world had ever seen an alleged confession by Colonel Ellis.”

Ellis was a historically important agent for the UK, and a colossus of spycraft in the US, Europe, Australia and Asia, but he was at his core a man who didn’t seek publicity and was quite happy to let others take all the glory.

Both in his actions and words, Ellis was an avowed opponent of the Soviet state.

A dubious circumstantial case has been made that he worked for the Soviets, both before and after the war. This, however, has never been proven. Ellis never made an outright confession that he supplied information to the Soviet Union; in fact, he categorically denied it. The most logical explanation for any “confession”, if such a confession was made and exists, is loyalty to his superiors. Ellis was probably protecting his superiors, likely MI6 chief Stewart Menzies, after the latter’s [pre-World War II] gambit against the Nazis was exposed and Ellis fell on his sword.

In a 1983 New York Times review of The LastHero: Wild Bill Donovan (which briefly mentions Ellis’s work with William Donovan’s Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the CIA) by Anthony Cave Brown, American journalist and author Edward Jay Epstein wrote: “Colonel Ellis remained an eminence grise in the OSS throughout most of the war. But the real importance of Colonel Ellis emerged only in 1965 … under gruelling interrogation by a team of British intelligence investigators, Colonel Ellis broke down and confessed that before World War II began, he had been recruited as a double agent by the Germans and then blackmailed into service by the Soviet Union.”

This was a blatant falsehood and misrepresentation. Cave Brown himself was appalled by the review, telling Interview magazine in 1983: “I have responded to a statement in The New York Times by Edward Jay Epstein that Colonel Charles H. Ellis … was, in fact, a Soviet agent. I mean, that story is just such patent balls that I’ve written a letter … to The New York Times regretting the fact that Mr Epstein, in an otherwise excellent review, found it necessary to betray the memory of a distinguished British officer.”

Throw enough mud, though, and some of it has to stick. b

This is an edited extract of The Eagle in the Mirror by Jesse Fink (Penguin Random House) to be released August 22.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout