Spies may have known for a decade that top gun Daniel Duggan was training China pilots

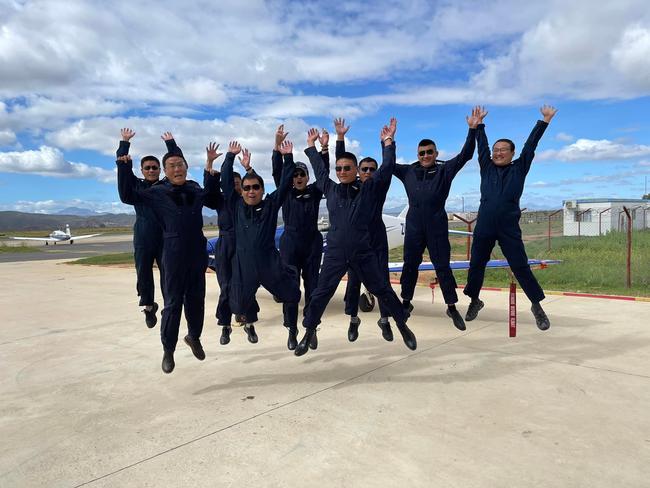

Western spies may have known for a decade that top gun Daniel Duggan was part of a group of western pilots training Chinese aviators through Test Flight Academy of South Africa.

Australia’s intelligence watchdog is investigating whether Western spy agencies knew for more than a decade that former top gun Daniel Edmund Duggan was training Chinese pilots through a controversial South African flying academy.

The Office of the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security is examining what interactions Australia’s intelligence services had with Mr Duggan, following a complaint from his defence team that the domestic spy agency ASIO may have been involved in “luring’’ him back to Australia in order to enable his arrest.

The allegation against ASIO was made in the context of the former US marine fighting a bid by the US to extradite him to face charges alleging he illegally trained People’s Liberation Army pilots, conspired with others to enable the training, and money-laundering.

While the claim against ASIO, and the fact the IGIS had agreed to investigate, has been made publicly, The Australian understand the intelligence watchdog is examining broader complaints, including whether intelligence agencies were aware Western pilots, including Mr Duggan, were training Chinese pilots through the Test Flying Academy of South Africa.

The academy, which denies any wrongdoing, has direct links to Chinese state-owned enterprises including aviation giant COMAC and is being scrutinised by intelligence agencies from the Five-Eyes alliance comprising the US, Britain, Australia, Canada and New Zealand.

It is believed that the Inspector-General, former Federal Court judge Christopher Jessup KC, is investigating any interactions between Mr Duggan and Western intelligence agencies, understood to include the period 2010-12, when he undertook a training contract with the academy. At the time he was an American citizen based in Australia. He became an Australian citizen in 2012.

The IGIS declined to comment on what timeframe its investigation was focused.

The possibility a Western intelligence agency – likely one of the US’s vast cyber-monitoring agencies – was aware of the activities of Mr Duggan and other Westerners in training Chinese pilots through the academy raises further intrigue about the timing of the charges laid against him.

Mr Duggan was arrested on a provisional warrant in the NSW city of Orange, where he lived with his wife Saffrine and their family of six children on a family farm, on October 21, three days after British media reported up to 30 RAF pilots had gone to China to train military pilots in return for big salaries.

Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus agreed to accept the extradition request from the US, a preliminary decision that allows the matter to go to court in Australia.

Mr Duggan strongly denies any wrongdoing.

His lawyer Bernard Collaery told The Australian that “I lose sleep over this family”.

Magistrates have to find a person is eligible and there is a probable cause to return them in order to sign an extradition. To determine if a person is eligible for extradition, the magistrate has to satisfy themselves that the offence alleged does not carry the death penalty, does not put the person at risk of torture, and was not of a political character.

Mr Duggan’s lawyers have told the court they believe the extradition application does involve matters of a political character.

If the magistrates does agree to extradition, Mr Dreyfus will make the final decision on whether to send Mr Duggan to the US. Mr Dreyfus has consistently declined to comment on the case.

One issue in the case is the relationship Mr Duggan had with Chinese-Canadian man Su Bin, also known as Stephen Subin, who was jailed in unrelated matters in 2016 for working with Chinese military officials seeking to hack into the systems of US defence contractors, including Boeing, hunting for military secrets.

Mr Duggan, who lived and worked in China for many years, was known to be familiar with Su, and shared an address with him there. The indictment says Su was the owner of a Chinese firm that “acquired military training, equipment and technical data for the PRC government military”.

Mr Duggan was also acquainted with former British top gun Keith Hartley, who was the chief operating office of the South African academy, and whose house in Adelaide was raided by police in November.

The academy, Mr Hartley and Su are known to be three of the eight unnamed co-conspirators cited in the indictment against Mr Duggan. Mr Hartley has not been charged, but the search warrants indicates police interest in him for the period 2018-22 – long after Mr Duggan’s contract with the flying school.

Another curious matter involves the money-laundering charges. Mr Duggan received 19 payments for his academy work, totalling $182,000. The payments appeared to have been deposited into his Commonwealth Bank accounts in Australia where he declared them to the Australian Taxation Office, and paid tax.

While not commenting on any specific case, Austrac, which monitors financial transactions, has told The Australian that all international transactions were automatically reported to it via financial institutions such as banks.

“There is not a skerrick of evidence suggesting any concealed payments,’’ Mr Collaery said. “This is an opportunistic misuse of the term money-laundering as understood in the Australian legal system.’’

Mr Duggan, who turned 55 on Saturday, has been behind bars for nine months and is in Lithgow jail.

His case, riven with claims and counter claims, geopolitics, complex legal arguments and intriguing hints about intelligence agencies, is underpinned by a solid public pressure campaign run by PR firm pCOMZ and helped along by public appearances by Mr Duggan’s family.

He has also retained Australia’s most expensive barrister, Bret Walker SC. He told the ABC in a jailhouse interview that he is selling his house and going into debt to fund the case, which he has said will cost “millions”. A crowd-funding campaign has raised just $14,000.

There is legal dispute over whether Mr Duggan’s case passes the “dual criminality’’ test, where an extradition requires the alleged offences offshore to also be a crime in Australia.

While Section 83.3 of Australia’s Criminal Code goes close, and restricts those with classified knowledge or skills learned in Australia from passing them on to foreign powers, it is not a direct mirror of the US laws. Defence Minister Richard Marles is reviewing whether any other Australian pilots have been involved in similar work to Mr Duggan, and said new legislation would be introduced to eliminate any doubt or confusion about eligibility to conduct such work.

Further documentation relating to what the US alleges has not been released. Lawyers appearing for the US government have said they have no objections to documents being released which contain more detail, but the court has declined to release the information to the media, with Mr Duggan’s legal team objecting to it on the basis it may be prejudicial.

What is known publicly is that the US says Mr Duggan went by a number of “aliases”, including Ding San Xing, Din San Qing, DSQ and Ivan. The US also references emails sent by Mr Duggan to Su about other business opportunities which “carry no risk”. This, the US argues, shows Mr Duggan was aware that “exporting defence services to PRC pilots was risky”.

Mr Duggan is accused of failing to obtain an export licence from the US State Department, something that is required if a person intends to perform a service for the benefit of a foreign person.

The US allege these services provided by Mr Duggan included “the evaluation of military pilot trainees, testing of naval aviation related equipment and instruction on the tactics, techniques and procedures associated with launching aircraft from, and landing on, a naval aircraft carrier”.

A court has yet to test whether Mr Duggan was providing training to civilian or military PRC pilots, and whether that affected his obligations to obtain an export license.

If IGIS does find western intelligence knew of western pilots training Chinese aviators, it’s unlikely to make any public comment on whether the spy agencies had any concerns about those activities at the time.

In the years Mr Duggan undertook the contract with the TFASA, the relationship between China and the west was very different. Xi Jinping wasn’t elected to the presidency until 2013, and enjoyed a few years of relatively hospitable relations with global leaders, before his muscular Chinese nationalism and expansionist ambitions soured relations.

In 2014, President Xi visited Brisbane for the G20 talks, where he was warmly welcomed and photographed alongside leaders Barack Obama, Shinzo Abe, Angela Merkel, David Cameron, and Narendra Modi. On that occasion, months after the downing of MH17, Russian President Vladimir Putin was the villain of the summit.

Mr Xi then walked through a corridor in Parliament House adored with Chinese and Australian flags, was given the rare privilege of addressing the Australian Parliament, was the guest of honour at a lavish banquet in Parliament’s Great Hall, and was lauded by then-prime minister Tony Abbott.

In 2015 on a visit to the UK, Mr Cameron took him to a local pub near Chequers, the prime minister’s country retreat, for a pint of lager and a quintessentially British meal of fish and chips. Amusingly, the pub was bought out by a Chinese investment firm a year later.

And in the same year, Australia and China signed a free trade agreement, a deal years in the making which promised to smooth the provision and trade and services between the two countries.

“They are in effect accusing him of consorting or aiding the enemy at a time when the US and Australia were expanding and promoting their trade opportunities with China,’’ Mr Collaery said.

“For Australia in particular, we were negotiating the China Australia Free Trade Agreement in which the services section contained no reservation (exemptions) by Australia.’’

The case returns to court in Sydney on November 24.