Sinister spy who stole bomb secrets made the world a safer place

Klaus Fuchs, a shadowy and often overlooked figure in Oppenheimer, assured a balance of power by giving the Russians atomic secrets.

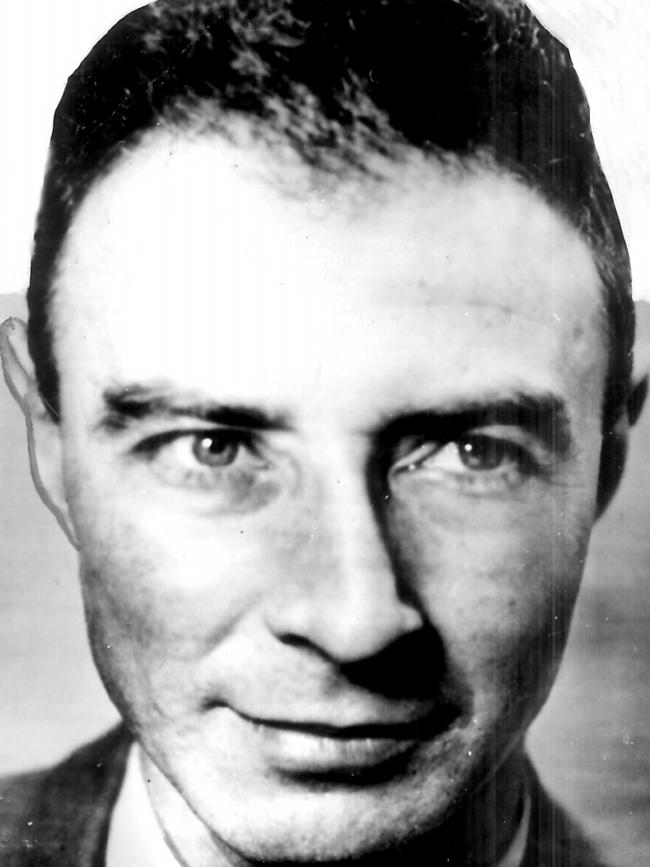

There is a character in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer who lurks in the background of many scenes; a tall, balding, shadowy figure without a single line of dialogue. But he is the second-most important person in the story of the atomic bomb. J. Robert Oppenheimer built the bomb. And Klaus Fuchs stole it.

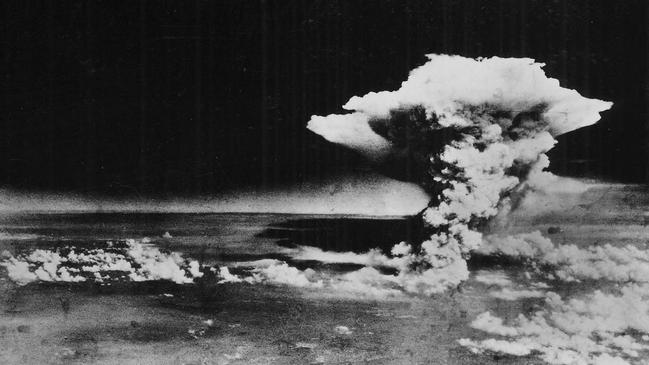

The Manhattan Project, and the Los Alamos Laboratory under Oppenheimer, produced the first nuclear weapons. The project cost some $3bn (about $30bn today) and employed 130,000 people. One of them was Fuchs, a brilliant physicist and a KGB agent, who passed those dangerous scientific secrets to Stalin, enabling the Soviet Union to build its own bomb.

In the film, Fuchs is simply described as “a British spy”. This is true, but misleading: Fuchs had been granted British citizenship shortly before the Manhattan Project was under way, but he was a German communist, a fierce opponent of Nazism who fled to Britain with the Gestapo on his trail.

Like Oppenheimer, Fuchs is an ambiguous and polarising character. A congressional hearing concluded he had “influenced the safety of more people and accomplished greater damage than any other spy in the history of nations”.

But by helping the USSR to build the bomb, Fuchs also helped to forge the nuclear balance of power, the precarious equilibrium of mutually assured destruction under which we all still live. Oppenheimer changed the world with science; Fuchs changed it with espionage. It is impossible to understand the significance of one without the other.

The son of a Lutheran pastor, Fuchs came of age in the economic chaos and violent political conflict of Weimar Germany. Like many young Germans, he embraced communism, the creed from which he never wavered. He was studying physics at Kiel University when his father was arrested for speaking out against Hitler. His mother killed herself by drinking hydrochloric acid. Returning from an anti-Nazi rally, he was beaten up and thrown into a river by fascist brownshirts. The German Communist Party told him to flee.

Fuchs arrived as a refugee in Britain in 1933 and, like many scientists escaping Nazism, he was warmly welcomed by the academic community. At Edinburgh University, he studied under the great physicist Max Born, another German exile. Fuchs was extremely clever and very odd: chain-smoking, obsessively punctual, myopic, gangling and solitary, the “perfect specimen of an abstracted professor”, in the words of one colleague. He kept his political beliefs entirely concealed.

In March 1940 two more exiled German scientists working at Birmingham University, Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls, outlined the first practical exposition of how to build a nuclear weapon, a device “capable of unleashing an explosion at a temperature comparable to that of the interior of the sun”. Peierls recruited Fuchs to join him in the top-secret project to develop a bomb, codenamed “Tube Alloys”. Soon after, Fuchs began passing information to Soviet intelligence. His handler was Ursula Kuczynski, a British housewife living in the Cotswolds who was also a colonel in the Red Army intelligence service, codenamed Agent Sonya. They met on quiet country roads around Banbury; the “dead drop” site for passing intelligence was a lay-by on the Oxford-to-Cheltenham road.

Between 1941 and 1943, Fuchs (codenamed “Otto") handed over 570 pages of information from the nuclear weapons project: reports, calculations, formulae and diagrams, a step-by-step guide to the science of atomic weaponry.

When Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt agreed to collaborate on building the bomb (while excluding the Soviet Union), “Tube Alloys” was absorbed into the far more ambitious Manhattan Project. Fuchs was one of 17 British-based scientists to join Oppenheimer at Los Alamos.

Fuchs’s first contact with his KGB handler in America, a communist named Harry Gold, was a scene straight out of John le Carre. They met on a New York street, with signals prepared: Gold wore one pair of gloves and carried another; Fuchs held a green book and a tennis ball. “Can you tell me the way to Chinatown?” he asked. Had anyone overheard this glaringly obvious spy contact our world would be a different place.

“I never saw myself as a spy,” Fuchs later insisted. “I just couldn’t understand why the West was not prepared to share the atom bomb with Moscow. I was of the opinion that something with that immense destructive potential should be made available to the big powers equally.”

In June 1945, Gold was waiting on a bench in Santa Fe when Fuchs drove up in his dilapidated car and handed over what his latest biographer calls “a virtual blueprint for the Trinity device”, the codename for the first test of a nuclear bomb a month later.

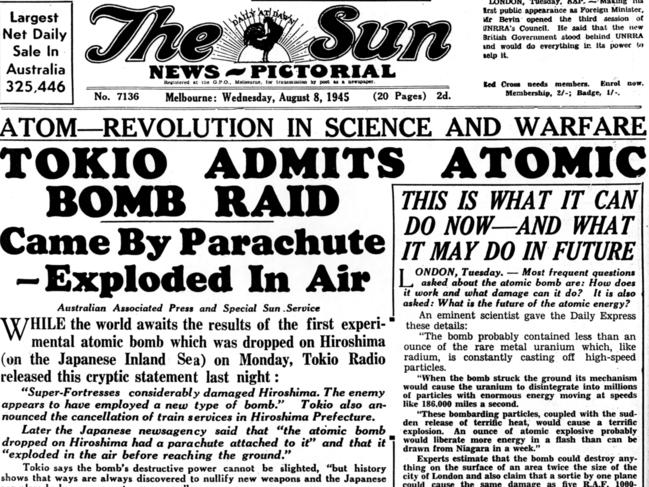

When the Soviet Union carried out its own test in Kazakhstan in 1949, the CIA was astonished, believing Moscow’s atomic weapons program was years behind the West. America’s nuclear superiority evaporated; the atomic arms race was on.

Fuchs was finally arrested in Britain in 1950. MI5 and the FBI blamed each other for lax security. He served nine years in prison and was greeted in East Germany as a hero. East German spymaster Markus Wolf wrote that Fuchs “changed the world’s balance of power by breaking America’s nuclear monopoly”.

Fuchs was a naive narcissist and a traitor to the country that gave him shelter. He was entirely obedient to his KGB masters, who justified his actions with hindsight. But without him, there might have been only one superpower.

Some in the Truman administration argued the bomb should be used on the Soviet Union before it developed its own. Fuchs and the other atomic spies enabled Moscow to keep nuclear pace with the West, maintaining a fragile peace.

As the father of the atomic bomb, Oppenheimer made the world markedly less secure. Fuchs, paradoxically, made it safer.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout