Oppenheimer shows that we are all bit players

It is not without its flaws. It is difficult to hear the dialogue, particularly in an Imax cinema where the non-stop score combines with frequent bone-shaking rumbling and explosions. And the episodic, interwoven narrative sometimes creates baffling lacunae.

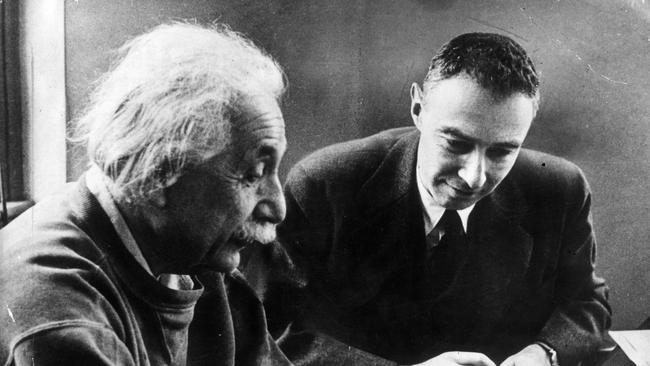

However, these are details. The film is magnificent, both in the acting and in the moral and political complexities that it extracts from what J Robert Oppenheimer did and what was done in turn to him.

It draws out his many ambiguities as a fellow traveller of the Communist Party in support of its opposition to fascism. It also explores with unsparing focus both his growing anguish over what he knows he is unleashing and the self-indulgence of his hand-wringing over what he nevertheless brings about.

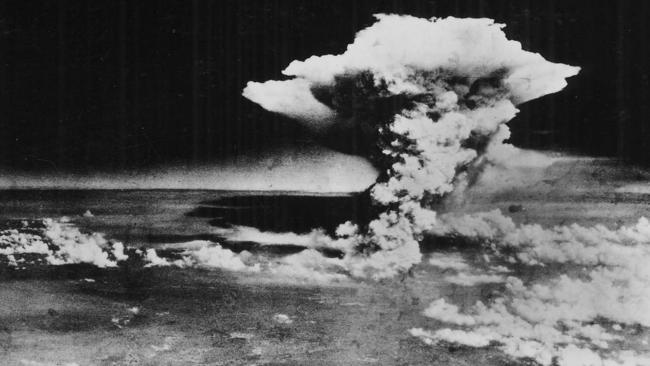

The great question is whether it could ever be right to vaporise thousands of people and cause others to die a slower and awful death, even if – according to the American analysis at the time – many more would otherwise have died to achieve victory over Japan. This dilemma is refracted through Oppenheimer’s increasing horror at what he is creating.

He knows that the bomb won’t just incinerate two Japanese cities. It will change the world utterly by sentencing it to lie for ever under a proliferating mushroom cloud of threatened annihilation. But the film is more profound still. For beyond these enormous issues, it projects a yet more shattering understanding of the terrifying existential meaninglessness that defines the modern age.

We see this almost from the start as the young physicist stares into the universe, realising that when stars die they collapse into themselves and create an unimaginable negation of existence, in what we now know as “black holes”.

Through the extraordinary, fathomless blue eyes of Cillian Murphy, who delivers an unforgettable performance as Oppenheimer, we find in his expression something beyond astonishment. We see also disorientation and even terror, as the certainties that previously anchored him to the world are snapped by mathematics and quantum physics, leaving him suspended in a universe beyond meaning.

The film underlines this through a set of fleeting images of what draws the young Oppenheimer’s interest outside the lecture hall. All are emblems of a culture that has snapped its philosophical moorings.

He studies a Cubist painting by Picasso that disassembles a woman into jarring components, creating the primacy of conceptual thinking and a new reality composed of the ambiguities and relativism of different perspectives. He reads TS Eliot’s great poem The Waste Land, that defining elegy for a world of purpose that was vanishing with the religion that had provided it. Oppenheimer’s monstrous creation will of course lay waste to Japan; but his real waste land is a world in which the absence of faith has turned existence into a set of random occurrences.

He is fascinated by the Bhagavad Gita, the Hindu holy text from where he quotes the line with which he will for ever be associated: “I am become death, the destroyer of worlds”. The Bhagavad Gita also became a talisman for people who, having renounced the biblical basis of western society, embraced instead eastern religions as having a supposedly universal message which flattens all differences and hierarchies. This was hailed in 1975 by the ecological savant and physicist Fritjof Capra, in his book The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism, as “a giant cosmic dance” of energy and particles, which he believed was the dance of the Hindu god Shiva.

Oppenheimer is presented as a universalist who believes – or rather, desperately tries to convince himself – that the brotherhood of man will somehow prevent a global nuclear apocalypse. The film suggests, however, that at the heart of these post-religious western beliefs lies a tragic paradox.

This is because, although human beings have never been more powerful, they have made themselves more cosmically insignificant than at any time since the Bible elevated humanity to moral grandeur. Oppenheimer developed the power to destroy the world; but as much as he wanted to, he couldn’t control the unstoppable forces of destruction he thus unleashed.

After the two nuclear strikes on Japan end the war, Oppenheimer is feted like a god. Waving away the adulation, he nevertheless demonstrates his self-absorption by telling US president Harry Truman that he feels he has “blood on my hands”. Truman responds with the savage observation that the Japanese couldn’t care less who invented the bomb that vaporised their cities: the only person they care about is the American president who gave the order.

In similar vein, a key atomic energy official who detonates the blowing up of the physicist’s reputation because of perceived slights is brutally told by an underling that he, too, was never the central figure that he imagined himself to be. We are all ultimately bit players in other people’s stories.

The real poignancy of the film lies in the way in which, beyond the drama of a tortured genius, it presents the individual being sucked into an existential black hole, just like the imploding stars that so trouble Oppenheimer at the start of his career.

It’s the perfect film for the post-religious age.

The Times

For once, the hype is justified. Oppenheimer, the blockbuster film about the godfather of the atomic bomb, is as superlative as its reviewers have said.