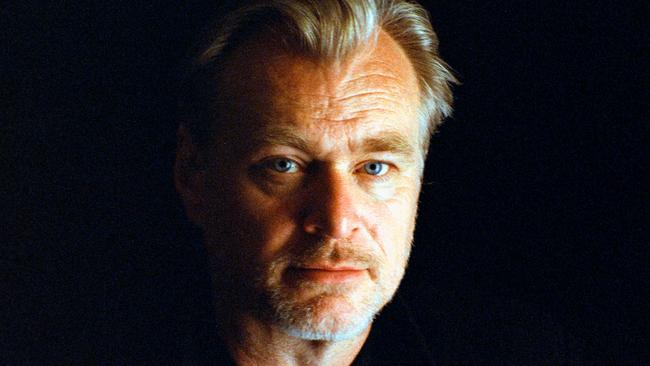

The master at work: a day in the editing suite with director Christopher Nolan

Come inside Christopher Nolan’s editing suite as he put the finishing touches on his ‘propulsive and highwire’ Oppenheimer – the biggest film of 2023.

The dub stage on the Warner Bros backlot in Burbank, California, looks like the bridge of the Starship Enterprise; and film director Christopher Nolan is Captain Kirk. A row of computers is arranged, crescent-like, before a screen large enough to be found in a suburban multiplex, but that pales against the kind that the filmmaker hopes people will see his movies on. (When it comes to the theatre going experience, the auteur is IMAX all the way. Before my interview with Nolan, the studio screened for me the trailer for his latest project Oppenheimer on the biggest IMAX screen in Los Angeles. “It’s five storeys high,” Nolan’s assistant Andy informs me, reverentially.)

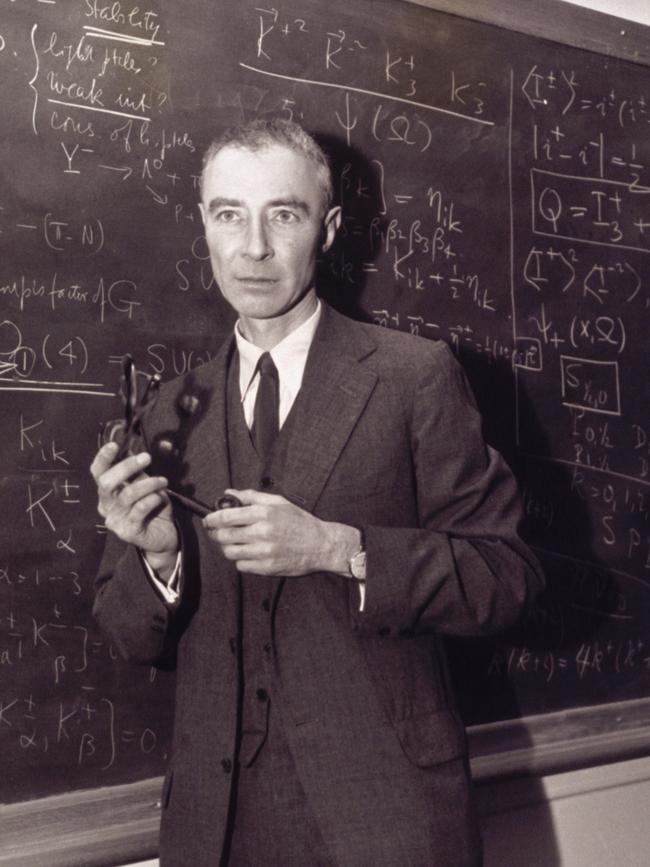

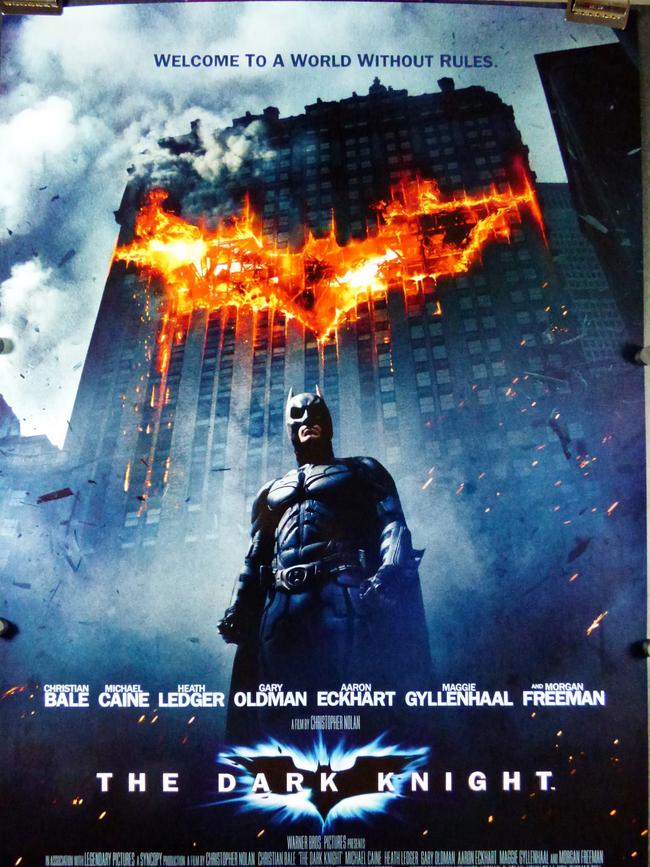

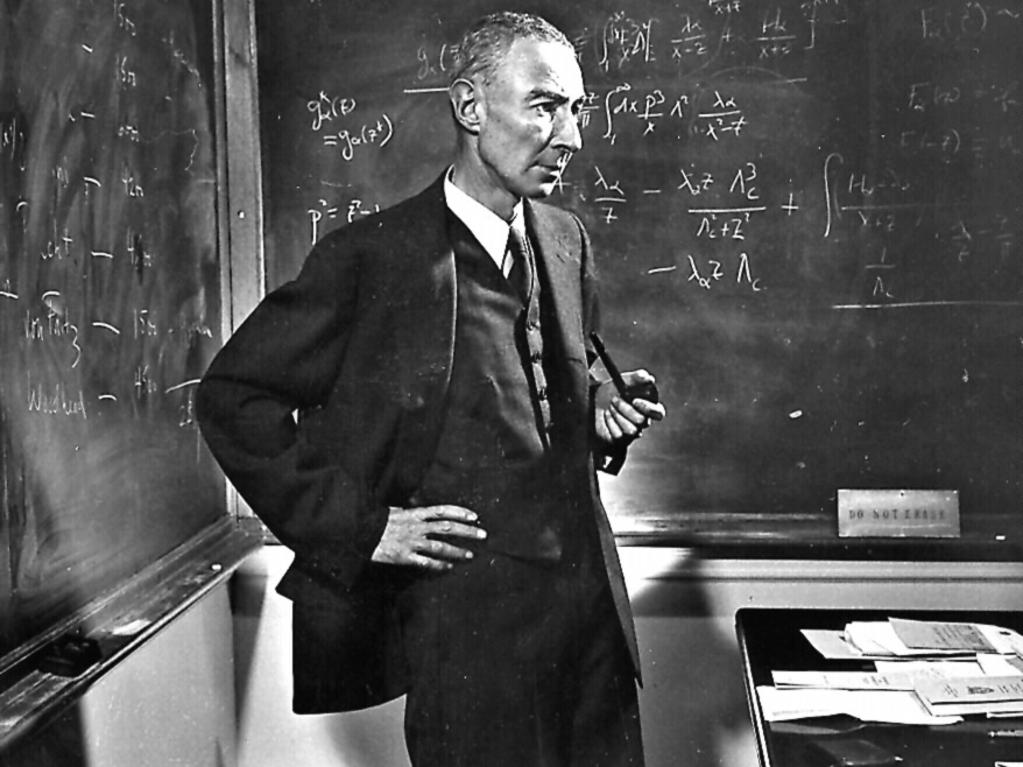

It’s January and Nolan is in the final stages of sound editing on Oppenheimer, the director’s biopic of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the inventor of the atomic bomb. Oppenheimer is Nolan’s 12th and arguably his most ambitious work yet. It is a movie with a budget of $US100 million, about a moment in history whose outcome we all know, without the brain-bending dazzle of his breakthrough cult hit Inception or his A-list space odyssey Interstellar, removed from the beloved comic book source material of his acclaimed The Dark Knight trilogy, and anchored not by a major movie star but by Nolan’s six time collaborator, the Irish actor Cillian Murphy. To be clear: these are all good things. That Nolan is making a serious drama for grown-ups is thrilling. (Oppenheimer has received an R rating in the US and at the time of print was still unclassified in Australia.) But it is, nonetheless, a gamble. Oppenheimer will be released by Universal, the first Nolan movie in more than two decades which will not be distributed by Warner Bros, his studio since 2002’s Insomnia. The film is shackled with expectations and is releasing in the middle of July in a corridor usually reserved for blockbusters. Which is what Nolan movies are: star-studded epics that have made more than $US5 billion at the box office collectively.

Nolan, dressed neatly in his uniform of blazer, vest and slacks, a blue scarf wrapped around his neck, paces in front of the dub stage monitors, sipping periodically from a mug of tea. The director has been here before, literally; he mixed The Prestige, his magician drama starring Hugh Jackman in this very room. A sound editor rolls a clip from the film. The face of Queenslander Jason Clarke fills the screen, as prosecutor Roger Robb interrogating Murphy’s Oppenheimer. The scene is shot in IMAX on black and white film and the contrast is like watching the granular detail of a daguerreotype leap into life. “You could use a shovel in making atomic weapons,” Oppenheimer says, evenly. (Murphy’s American accent is impeccable.) “You could use a bottle of beer, in fact you do!”

The clip plays a few times. “He says ‘bottle of beer’ in a different way,” Nolan frowns, peering into the monitor. The director repeats the word bottle, rolling it around in his mouth. “To me it’s just a little scrappy, but it’s different.” Someone marks the clip for changes. “While we’re there, I think the last of the ‘bottle of beer’ is a bit low,” Nolan adds. I am sitting towards the back of the room, trying to be as unobtrusive as possible in the presence of film legend. Next to me is Emma Thomas, Nolan’s producing partner – and also his wife. “As you’ll see, Chris is something of a perfectionist,” she whispers, with a smile. More vignettes flash across the screen. The young physicist in a lab coat. Emily Blunt, who plays Oppenheimer’s wife Kitty, riding a horse. Florence Pugh, who stars as Oppenheimer’s “close friend” Jean Tatlock – history book speak for “ex-girlfriend/mistress” – with mascara running down her cheeks. Robert Downey Jr, who returns to the big screen in Oppenheimer for the first time since Avengers: Endgame as Lewis Strauss, the chairman of the US Atomic Energy Commission and the film’s second lead, descending a flight of stairs at a clip. Out of context, the footage provides scant clues about the plot, historicity or even the mood of Oppenheimer, which, like all Nolan movies, wears its secrecy like a perfectly tailored suit.

Nolan sits down to make a few more changes. In a scene where a gaggle of scientists arrive at Oppenheimer’s nuclear test site in the pouring rain, Nolan requests the score – by Ludwig Goransson; indelible, violin forward, and yes, loud – be turned down a notch so that the squelching of boots can be better heard. Every time Nolan makes a change, a team member marks it down. At this stage of the process, it’s microsurgery. “It should be a straight transfer,” notes one, in response to a query about sound files. “Should is my least favourite word,” Gary Rizzo replies, cautiously. Rizzo is Nolan’s sound mixer, a two-time Oscar winner for his work on Inception and the World War II thriller Dunkirk. He was also nominated for The Dark Knight and Interstellar.

Nolan weighs in. “I’m okay with should, because it is acknowledging the possibility of failure and alerting you to it,” he muses. Nolan characters often live in the world of should, of weighing up all the variables as they strive through uncertainty to reach the right conclusion. Think of Interstellar, where a man pilots a spaceship through a wormhole to reunite with his family. Or even Nolan’s Batman, who arrived in a sleek, Christian Bale-shaped package in 2005 and changed comic book movies forever by daring to ask the question: What if a hero was to fail?

“What about shouldn’t?” poses one of the mixers in the room. Nolan reflects on that for a moment. The “bottle of beer” clip returns to the screen and rolls a few more times. The line is almost there, but not quite. Nolan leaps out of his chair. “Should we break for lunch?”

Nolan,who commands the kind of devotion usually reserved for those in front of the camera, is spending his lunch hour with The Weekend Australian Magazine. The director is 52 years old, but the only indicator of his age is his hair, formerly blonde and now mostly a very light, silvery grey. He has a boyish face and a cheerful energy, particularly for someone who is in the final stages of editing a drama with a nine figure budget that is shouldered with all the hopes of a flagging theatrical business, an industry that still dreams of another original Nolan hit like the $US868 million grossing Inception. Since the pandemic, cinemas have been in desperate straits: the global box office take in 2022 was just $US22 billion; in 2019, that number was a record $US42.5 billion.

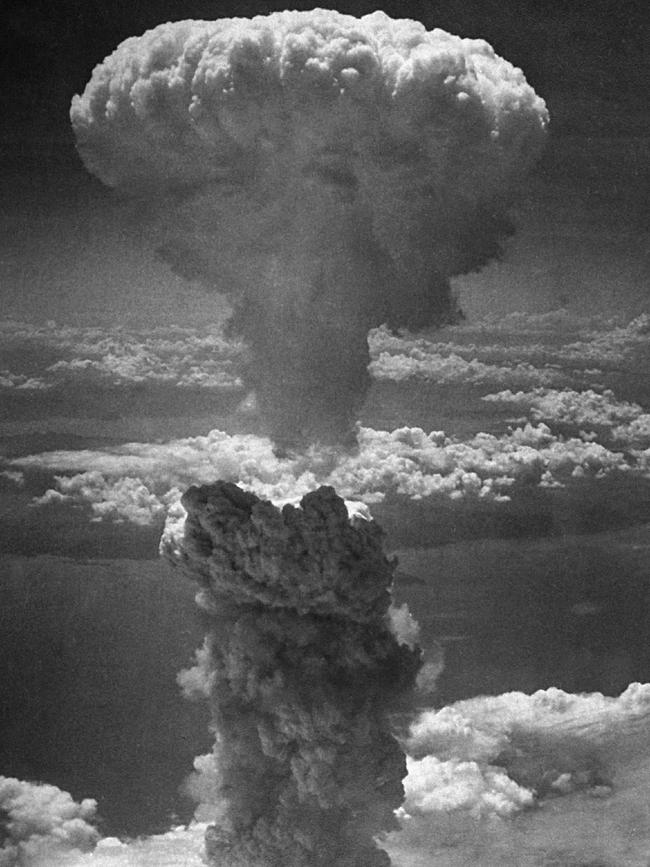

Not that Nolan considers that his responsibility. “I think my job is to make films that I want to see, that I’m passionate about, and that’s all I can do,” he demurs. “I think if you start thinking beyond that, it’s confusing for you as a craft.” Regardless, if he is feeling the pressure, he doesn’t show it. We adjourn to a small lounge, where his assistant appears wordlessly with a fresh cup of tea. Nolan has been fascinated with J Robert Oppenheimer for a long time, but the obsession grew during production on his 2019 film Tenet. That film, a heist thriller told (sort of) in reverse, hinges on an algorithm created by an unnamed scientist referred to in the film as the “Oppenheimer of her generation”, who pledged to risk the world in order to save it. It’s the same realisation that the Oppenheimer of his generation had in July 1945 when he created the first nuclear explosion during the Trinity test, despite knowing there was a chance he could ignite the atmosphere in the process. “The scientific achievement is second to none,” says Nolan, but the consequences were “staggering and enormous and profound”.

In August 1945, atomic bombs were dropped on Japan, effectively ending WWII. After the war, Oppenheimer became a prominent voice against nuclear proliferation, arguing for control over the power that he created. What about shouldn’t?

Tenet star Robert Pattinson gifted Nolan a book of Oppenheimer speeches after production wrapped. Reading them, the director zeroed in on what the man represents to him, dramaturgically: real world events with superhero stakes. “To get ahead of the Nazis and come up with the atomic bomb before they did,” Nolan sums up. A blockbuster pause. “And save the world.” But with great power comes great responsibility. In the Oppenheimer speeches, delivered after 1946, “you are hearing the minds that unleashed this extraordinary power, trying to reconcile that with the safety and security of the world,” Nolan reflects.

“This man, for better or worse, did change the world,” sums up Blunt. “And he changed the way we war with each other as well.” Production on Oppenheimer began in February 2022, the same month that war broke out in Ukraine. “A lot of atomic bomb threats were in the ether,” says Blunt. “The poignancy of making a film about the birth of it at the same time was wild, to be honest with you. We talked about it a lot on set.” Nolan, who writes almost all of his films, penned the script for Oppenheimer based on the 2004 biography American Prometheus. Nolan “just devoured” the book. One particular detail struck him: the site Oppenheimer chose in Los Alamos to be the stronghold of The Manhattan Project – the organisation established to create an atomic bomb – was situated on a camping ground the physicist frequented in his childhood. “There’s something deeply personal about that,” Nolan muses. “That’s an extraordinary moment of human whim and emotion pushing massive political events in a particular direction.”

The intersection of the personal and the profound: plots don’t come more Nolan-esque than that. Think back to Inception, when Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) risked getting stuck five layers deep in the dreamscape of an unwitting businessman – played by Nolan’s future Oppenheimer, Cillian Murphy – just to spend one more second with his dead wife. “In the fictional material that I’ve done, I’ve always been interested in paradox,” he explains. Should versus shouldn’t. “Characters who have dilemmas for which there are no simple answers … I’ve simply never seen any figure, either historical or even in fiction, who has quite the level of paradox [asOppenheimer].”

Oppenheimer the man is unsurprisingly the focus of Oppenheimer the film; so wedded is the physicist’s perspective to the narrative, Nolan wrote the script in first person, “which I’d never done before”. Blunt describes the experience of reading it as “being kidnapped” by that subjectivity. Nolan’s objective was to put the audience right alongside Oppenheimer as he processes the consequences of nuclear power. “The film doesn’t attempt to judge him. It attempts to give you his experience,” he explains. “Make of it what you will.”

But this approach only works with the right actor in the leading role. For Nolan, it could only be Murphy. “I’ve known Cillian a long time at this point, 20 years more or less,” he reflects. “I’ve known him to be the finest actor of his generation.” Murphy’s first Nolan film was Batman Begins. He auditioned for the role of the hero (which went to Christian Bale) but ended up cast as the villainous Scarecrow. Murphy appeared in two subsequent Batman movies, in Inception and then Dunkirk, as a soldier haunted by war. Nolan remembers sending Murphy the script for the timeline-twisting World War II thriller. “He called me after he’d read it and was kind of like, ‘Can’t I play a Spitfire pilot instead?’” Nolan laughs. “‘No, I need you on that boat. We have to find how that character is going to work’ … He’s brilliant at that.”

Oppenheimer realises a long-held ambition for Nolan, which was to write a leading role for Murphy, an empathetic and intelligent screen presence most known for his work on the Netflix series Peaky Blinders. It was an ambition for Murphy, too:

“I always hoped I could play a lead in a Chris Nolan movie. What actor wouldn’t want to do that,” he recently told Rolling Stone. (Blunt says she would have signed on to Oppenheimer even if her character appeared in a single scene.)

The role is a challenge. The movie isn’t what Blunt calls a “dusty old biopic”. “This thing grabs you in a vice-like grip and it never lets go,” she raves, “it’s a heart racer. Like, you might need a drink after it.”

But it is a decades-spanning story that follows Oppenheimer from his idealistic student days all the way to after the bomb. And Murphy is tasked with carrying the film, which at almost three hours is the longest of his director’s career. Nolan had faith in his star. “You can really jump into his head and look in those eyes and understand the journey you’re on, and that was vital for this. This isn’t a character I want to be looking at from the outside.” For much of the movie, Nolan rammed his enormous IMAX camera – loaded with impeccable 65mm film stock; the final print of the film runs more than 17km long – right up to Murphy’s face. “You want to be with him really experiencing it.”

The rest of the ensemble is a roll call of film stars: Blunt, Pugh, Downey Jr, Matt Damon, Kenneth Branagh, Josh Hartnett, Gary Oldman, Rami Malek. “Working with such a director and cast was an immediate yes,” says Pugh. She describes the atmosphere on set as “high in energy and attention”. “Everyone is working to the best of their ability and so you really do feel this fast-paced, focused rhythmic work ethic that does not stop until you wrap. It’s extremely exhilarating and a wonderful atmosphere.”

The star power on screen is as electrifying as the visuals. After being granted permission for a rare early screening, I can confirm the film is as propulsive and high wire as anything Nolan has made, but cut through with an unsettling aura of devastation. Oppenheimer is, quite simply, a huge movie, wrestling with the weighty moral dilemmas of war and those in the post-war wake left to pick up the pieces.

“I felt like it wrapped its arms around me and pulled me into the screen,” shares Blunt. “And I realised this isn’t just a film, this is an experience, and you don’t get to be a part of many like that.” Blunt, speaking on Zoom from her home in New York, says this in something of a daze. “We’re all a bit starstruck by the movie,” admits the actor, who is married to actor/director John Krasinski. Later, she tells me that, while she loves Dunkirk and The Dark Knight, she thinks that Oppenheimer might be her favourite film from the director’s oeuvre. (“I will say, it’s John’s favourite Christopher Nolan movie,” she shares.)

“I’m trying to remember which playwright wrote that when a gun is introduced in the first act, it has to go off in the third act,” Nolan muses, halfway through our conversation. (Chekhov.) “It seems to apply to life as well, which is a little scary.” What he means is that if you create an atomic device, at some point comes the terrifying realisation that it will be detonated. Chekhov’s bomb is the “hinge” upon which Nolan’s film hangs, and the director tasked his visual effects supervisor Andrew Jackson with staging the first nuclear detonation without using CGI. Nolan is renowned for his dedication to practical effects because he believes they are the only way to truly convey threat on screen, something of paramount importance in a film about atomic weaponry. “It’s really difficult to make computer generated imagery threatening,” Nolan reflects. “It’s very difficult to make it tactile. And if it doesn’t feel real, it can be great eye candy, but it’s not going to have the same weight and validity and therefore threat as the other real elements that are in the film.”

For Oppenheimer, Jackson and his team “immediately started coming up with very interesting ideas and things we could put a camera on,” Nolan says, giddily. Anything in particular he can share? “No,” he laughs. The final result is a combination of awe-inspiring practical effects and a seat-shaking sound mix.

Over-reliance on CGI is, in Nolan’s view, an inability to problem solve. “It really becomes an attractive proposition for just not dealing with things in the moment,” he explains. When everything can be “fixed in post”, why bother getting it right on the day? “But the danger there is things aren’t made coherently and cohesively.” Nolan is famous for his practical world-building: real effects on real sets at real scale. “Everything is practical,” Blunt says. “I love that, because it feels like you’re making something important and you’ve got someone who is conducting the whole thing who has thought of everything and sweated every detail and wants it to be uncompromisingly great. That air surrounds the whole set. It permeates every department.”

Costume designer Ellen Mirojnick recreated ’40s suiting for Murphy, while production designer Ruth De Jong rebuilt the exteriors of Los Alamos in New Mexico. Interiors were filmed at real locations, including Oppenheimer’s actual home. “You feel the ghosts of the people,” Blunt says. “It’s tingly.”

Nolan has always made his movies with as few shots requiring visual effects as possible: consider just 430 fx shots in The Dark Knight Rises, and only 280 in Tenet. To put this into perspective, Avengers: Endgame contained an astonishing 2698; Nolan’s post-production co-ordinator has said that he has worked on romantic comedies with more visual effects than The Dark Knight Rises.

Oppenheimer has, Nolan says, the smallest number of visual effects of any film in his career. “I mean, the nature of the story is less fanciful,” he begins. But there’s a pretty big bomb in Oppenheimer, I point out. “Exactly,” he grins.

This year marks 25 years since Nolan firstgot into the movie business. Instead of film school, Nolan studied English, and in the mid ’90s began work on his debut: a drama about London’s criminal underworld called Following. Nolan shot the movie himself on weekends in hard-to-wrangle locations such as his family home; his mother made sandwiches for the cast and crew. What does Nolan remember about that time? How has life changed? “Gosh,” he says, pausing. “In film terms, everything feels the same.” Following screened at international festivals in 1998 to positive reviews, which led to Nolan and his brother Jonathan, who would go on to become creator of the HBO series Westworld, writing the script for his breakthrough, 2000’s Memento, starring an up-and-coming Guy Pearce. In just two years, Nolan went from shooting a movie in his spare time to one starring a bona fide Hollywood star.

“Every experience you have is as valid as another,” Nolan reflects. This is what he tells film students when they come to him for advice. “For me, the process of building Los Alamos on a hill [in Oppenheimer] is exactly the same as it was making Following on the weekends, and doing it in a much scrappier way,” he says. “In fact, in some ways, [cinematographer] Hoyte van Hoytema and myself doing Oppenheimer, we didn’t have any technocranes or steadicams or anything like that, we worked with a very stripped down unit of just one camera.” He smiles a little sheepishly as he concedes, “It is an IMAX camera.” Nolan’s precision, and his singular vision, is the throughline of his career. With the exception of 2002’s Insomnia, Nolan has written all of his movies. He is famously efficient and hands-on, always shooting on real film. Even the video calls in Interstellar between Matthew McConaughey’s character and his son, played by a young Timotheé Chalamet, were shot on 35mm film. Actors love him. “He sure as hell knows what he’s doing,” DiCaprio told Empire in 2010. Blunt remembers asking Murphy what it was like to work with Nolan. “He said, ‘You’re going to absolutely love him.’ The process is so focused. You feel so safe in his hands.” As the hugely in-demand Pugh puts it: “He is a master of his craft and so you really do feel like you are there to show up and do the work he’s given you the opportunity to do at the best level possible.”

Audiences love him even more. Over the course of his career, Nolan has become a brand unto himself, a director with name recognition whose original ideas and ambitions when it comes to the structure of his films – dreamscapes stacked upon dreamscapes in Inception; Dunkirk’s alternating timelines woven together as one; the amnesiac puzzle of Memento; yes, even Oppenheimer has a structural conceit that we won’t spoil here – are hailed by film nerds and the mainstream alike. It’s why he’s not joking when he says that he doesn’t “want to engage in spoilers” in regards to Oppenheimer. “Absurd though it may sound in a true story, there are still spoilers. The film is still my interpretation.” Nolan knows that the valuable IP here isn’t history; it’s his own mind. And there are always ideas rattling around in there.

“I work on one thing at a time, but I do have these notions or things that interest me that sit in a drawer,” Nolan says. So it was with Oppenheimer, which he mulled over for years before working on it in earnest after Tenet, and so it is with the ideas that Nolan is thinking about even now – not that he will talk about them. “You must know I can’t,” Nolan counters, affably. (Blunt describes his calm, confident affect as like that of a treasured uncle. “He’ll hate me saying that,” she laughs. “But it’s true.”)

“It’s not even a question of being secretive or anything like that,” Nolan continues. “You can’t take things out of the oven too soon. Then the souffle falls flat, it’s gone, and you have to find something else. I think things bubble up to the surface when you’re ready for them.”

The cinematic souffle takes time. He can’t even do the thing he loves, which is see other people’s movies, when the souffle is still rising. “It sounds ridiculous, but if I’m prepping a movie, I’ll be looking at the movie like, ‘How much did that cost?’” he admits. “If I’m shooting the movie, I’m like ‘Where did they put the camera, how did they get the dolly through that door?’ If I’m mixing the sound, I’m listening to the footsteps.”

Nolan admires the work of next generation talents including Ryan Coogler and Damien Chazelle; he’s really looking forward to finally catching up to Chazelle’s Babylon when Oppenheimer is complete. He’s excited about a big year of movies ahead. “I feel very good about theatrical and where things are going,” he says. “I think some of the old ideas about how you could get rid of the window between theatrical and streaming, a lot of those things have been tried and have failed.” It was this that caused the rift between Nolan and his long-term studio Warner Bros, who made the decision to send their entire theatrical slate for 2021 direct to their streaming platform HBO Max. (Nolan had said in a statement to The Hollywood Reporter that Warner Bros “don’t even understand what they’re losing” and consequently took Oppenheimer to Universal. Two years on, Warner Bros still wants to woo Nolan back.) He asks me who I’m interested in and I tell him how intrigued I am by Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, opening the same week as Oppenheimer. He nods thoughtfully; he’s interested in her, too. “Doesn’t happen as much these days,” he says, “an indie director taking on a big studio film. We should do more of that.” After all, that’s how Nolan got his start.

He made a small budget indie on the weekends and then another, marginally less small budget psychological portrait with Memento before he transformed the idea of what a studio movie could be, by taking the themes and motifs that fascinated him as a young, scrappy filmmaker – time, reality, family, morality – and rendering them in breathtaking IMAX resolution. That’s Nolan’s gift, on display perhaps more in Oppenheimer than in many of his previous films, because of its streamlined focus on just one man trying to be on the right side of history.

“The way I like to put it is: the screen is the same,” Nolan explains, as our conversation winds down. The filmmaker has to go back into the dub stage and lock the sound mix on his ambitious historical drama.

“Cinema is photographing something, then photographing something else, which is going to influence something you just saw. A plus B becoming idea C, telling a story. And I’ve had as much fun working on a very micro, low budget level as I do at a high budget. It’s the same process. And that’s a part of my life that doesn’t change much,” he shrugs, happily. “It’s kind of nice, actually.”

Oppenheimer is in cinemas on July 20

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout