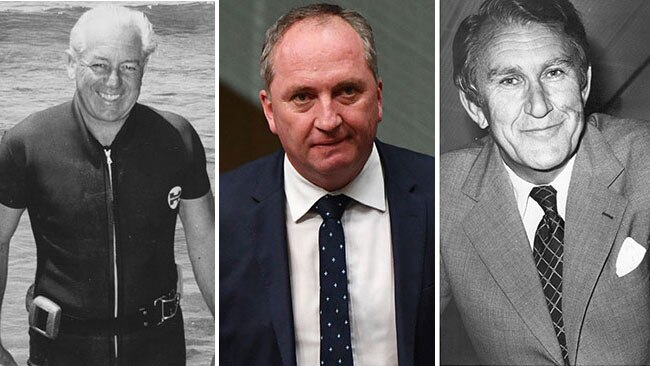

Barnaby Joyce is not the first Australian political leader to be embroiled in a sex scandal that has left many questioning his moral standards and, more important, examining whether there has been a breach of his public duties relating to travel entitlements, staff employment and accountability to the parliament.

But it is impossible to think Joyce can remain leader of the Nationals and Deputy Prime Minister; his authority has been badly diminished and his credibility eroded. He may have the support of most of his partyroom for now, but the vast majority of voters will never be able to trust him again and want him to go.

It would be better for the government if Joyce resigned from the leadership and the ministry, went to the backbench and quit parliament at the next election. But Joyce, ever the political fighter, has decided to continue on, regardless of the harm he is doing.

Joyce has only himself to blame for how poorly he has handled the revelation — made public a fortnight ago — that he had an affair with a former staff member who is having his baby. He has dodged and weaved snowballing allegations and refused to provide satisfactory answers to legitimate questions that relate to the discharge of his public duties.

As a result, it was untenable for Joyce to act as deputy prime minister this week. If the Deputy Prime Minister cannot be acting prime minister when needed, how can he continue in this role? That is his job. The government is paralysed by this scandal and the relationship between Malcolm Turnbull and Joyce has obviously been damaged. Why can’t Joyce do the right thing and resign?

The Prime Minister can’t risk sacking Joyce because it might rupture the Coalition, although he could recommend to the Governor-General that Joyce’s ministerial commission be terminated and Peter Cosgrove would surely follow this advice.

So the Liberal Party has to wait until its junior partner, the Nationals, takes responsibility and ends Joyce’s leadership.

Turnbull had begun to chart a comeback for the government in the polls, and had been sharper on politics and policy, before the Joyce imbroglio. As I have noted before, the government does not get enough credit for its policy achievements. Turnbull is a leader of intelligence and integrity, unlike his deputy. Turnbull’s standing has suffered because of Joyce’s transgressions.

If Joyce’s affair were discovered a generation ago, it might never have been revealed to the public due to the cosy relationship that existed between politicians and the media. And if it were disclosed, Joyce might have weathered the storm without the impact of social media and tabloid sensationalism. In any event, we now appropriately expect higher standards of personal behaviour in public and private life.

It was easier for Harold Holt, a serial philanderer who disappeared in the surf at Portsea while his mistress, Marjorie Gillespie, frantically looked on. Holt’s parliamentary colleagues, friends and journalists knew about the relationship but it was never publicly disclosed. Zara Holt said years later her husband “was having affairs everywhere”.

Holt is not alone among former prime ministers known for their dangerous liaisons. It has been suggested John Curtin had an affair with Belle Southwell, who managed the Kurrajong Hotel in Canberra. Ben Chifley is said to have had an affair with his secretary, Phyllis Donnelly, and her sister, Nell. It is alleged Robert Menzies had an affair with Elizabeth Fairfax. Yet evidence for these sex scandals is threadbare.

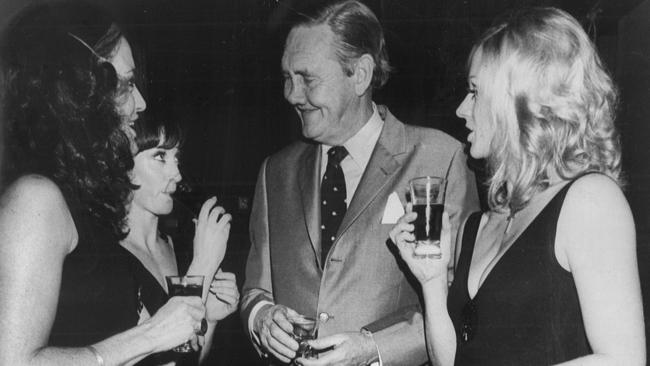

John Gorton acknowledged he had multiple affairs, though probably not while prime minister. Gorton loved to be in the company of attractive young women and frequently escaped from the Lodge to go to late-night parties in Canberra. Gorton also had a serious drinking problem.

Most prime ministers have endured salacious gossip about their private life that was almost always untrue. But Malcolm Fraser, often suspected of being a “pants man”, was literally caught with his pants down in a sleazy Memphis hotel in 1986. Drugged and robbed, Fraser appeared in the lobby with a towel wrapped around his waist.

Jim Cairns, deputy to Gough Whitlam, had an affair with staff member Junie Morosi. Cairns declared “a kind of love” for Morosi while married to his wife, Gwen. He later acknowledged the affair and admitted being “distracted” by it as treasurer. It didn’t stop Morosi, however, pocketing several large defamation payments in the 1970s.

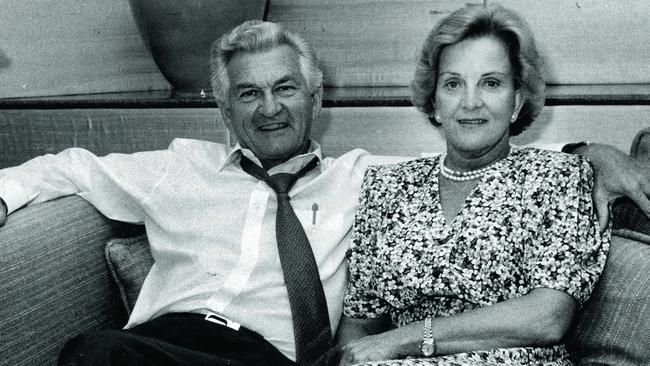

There have been comparisons made between Joyce and Bob Hawke. But these are erroneous. The difference with Hawke, who was known for his drinking and womanising in the 60s and 70s, is that he was always upfront about his faults and they never had an impact on his public duties. Hawke knew he had to change if he wanted to become prime minister. He gave up the drink and left the womanising, mostly, behind. Hawke renewed his love affair with biographer Blanche d’Alpuget in the mid-80s but — here’s the thing — he never lied about his infidelity, hid it or claimed moral superiority. And he didn’t sleep with his staff.

The voters, fully aware of Hawke’s history and knowing he was never hypocritical in his politics, made him prime minister and kept him there for nine years.

In 1989, Hawke acknowledged in a radio interview with Clive Robertson that he had not been faithful to his wife, Hazel. His popularity went up. Joyce is no Hawke. Voters will not tolerate lies, hypocrisy or sanctimony. It is time for him to go.

More Coverage

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout