Paul Keating makes case for voice to improve Indigenous lives

Paul Keating has broken his silence on the voice debate to hold up his Indigenous advisory group on native title as evidence that the idea works.

Paul Keating has given his full support to the referendum to provide constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians through a voice to parliament and government, as the campaign enters its final week.

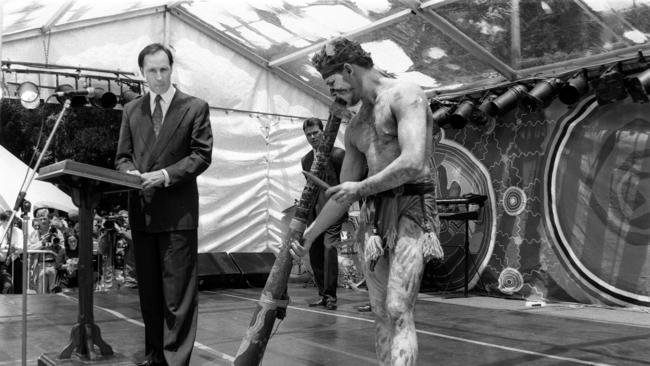

The former prime minister, who negotiated the Native Title Act in response to the High Court’s Mabo judgement with Indigenous leaders, told The Australian that a constitutionally enshrined advisory body would lead to systematic improvement in policy results across the board.

Mr Keating said his seven-month negotiation with Indigenous leaders on the complex issues of native title through 1993 showed that a standing advisory body could significantly enhance the policymaking process and increase living standards for Indigenous Australians.

“A voice can dramatically improve outcomes,” he said in a statement provided exclusively to The Australian. “The idea of a ‘voice’ has been tried and it worked. For this demonstration and a host of other reasons, I will be voting ‘yes’ on Saturday.”

In his first public statement on the referendum since the enabling legislation passed the parliament and the question to be put to voters was settled, Mr Keating said his Indigenous advisory group on native title informed the government and the parliament in its deliberations.

“We have already had demonstration of a ‘voice’ in respect of deeply complex issues once before and the overall outcome was sharply enhanced,” he said.

“The ‘voice’, on that occasion, was the concentrated consultation employed over a period of seven months between the commonwealth and Aboriginal and Islander people in respect of native title.”

Mr Keating said a similar constitutionally enshrined advisory body, responsible for making representations on matters that affect Indigenous Australians, and which does not diminish the parliament’s authority, would benefit policymaking across the spectrum.

“Without an Indigenous ‘voice’ to executive government, and with that, to the parliament, this historic opportunity would not have produced an optimum outcome of the kind that the Native Title Tribunal, in subject titles, was able to subsequently award,” he explained.

“While the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet at the time possessed a first-rate Aboriginal policy unit, its authority and grasp of issues central to Indigenous people would not have comprehended the quality and poignancy of advice and experience that Indigenous people across the country were able to provide.

“The long and tortuous seven months extended consultation through the native title process was the first and, so far, the only example of a ‘voice’ in the full throat of its advisory mandate but as it turned out, a mandate that went a long way to settling perhaps the primary Indigenous grievance; the theft of their estate.”

The former prime minister delivered the landmark speech on reconciliation at Redfern Park in December 1992, calling for “recognition” of the history and plight of Indigenous Australians, an opening of “hearts” and a commitment to improving living standards as the “practical building blocks of change.”

He initiated the inquiry into the forced separation of Indigenous children from their families – the Stolen Generations – led by former High Court judge Ronald Wilson, which reported in May 1997. His government also established the Indigenous Land Fund with $2bn to buy back pastoral leases to revive native title.

Mr Keating told The Australian that his negotiation of the Native Title Act with Indigenous leaders and also business and farming groups and state governments from April to November 1993 was the hardest thing he did in his time as prime minister.

“The consultation was the very first episode of an Indigenous ‘voice’ speaking directly to the executive government on a matter materially central to Indigenous people; namely, that the High Court had found Indigenous people possessed a private property right to their own soil – but a right immediately threatened with extinguishment by malevolent state governments,” he recalled.

“The urgency of the task, given the complexity, was to be met by comprehensive engagement by the commonwealth – the Keating government – with representatives of the national Aboriginal Land Councils under the chair of the then ATSIC.

“The challenge was to meet and settle two fundamental objectives: justice for Aboriginal people along with the development of a workable, fair system of land management in Australia.

“The High Court decision was silent on the nature of the ancient title it said had survived the act of sovereignty by Britain. It was also silent as to where that title lay, who could enjoy it, as it was silent as to a method Indigenous people could employ to recover it.

“This was left for the executive government to do.

“This necessitated me, as prime minister, attending native title cabinet committee meetings for three days and evenings a week for seven months leading up to the passage of the Native Title Bill through both houses.

“And during those seven months, Indigenous representatives … would intermittently attend cabinet committee discussions.”

The ultimate result, he said, was that after protracted negotiations, the policy outcome was superior to what it otherwise would have been. This process demonstrates the benefit of a voice to parliament and government.

Troy Bramston is the author of Paul Keating: The Big Picture Leader (Scribe)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout