Why was the 1967 referendum different to the Indigenous voice to parliament vote?

Why was the 1967 referendum different to the Indigenous voice to parliament vote? There are many explanations but race lies in the foreground.

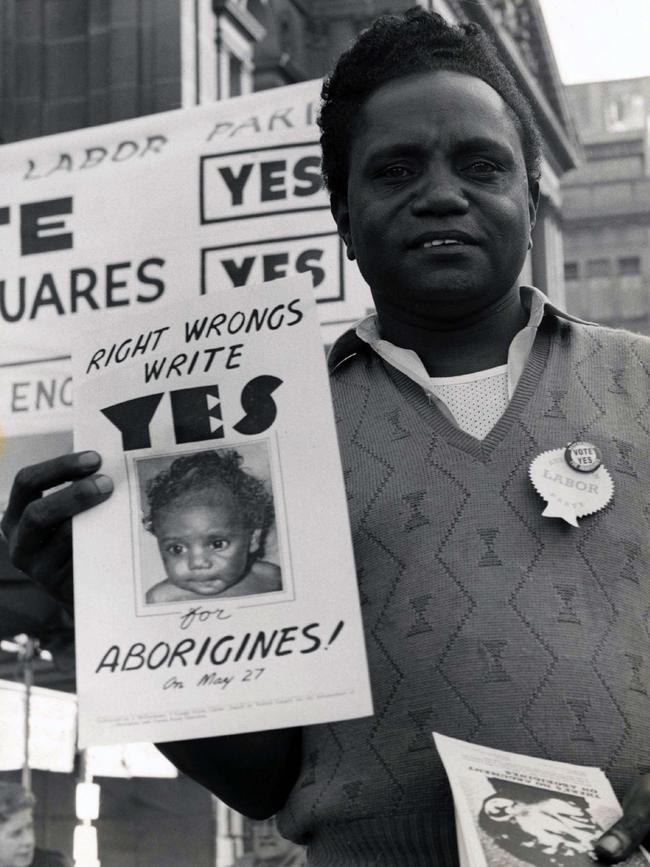

With the White Australia policy still in place, our parliaments devoid of any Aboriginal MPs, the people spoke as one, resolute and united across every state and every region, changing the Constitution in the cause of Aboriginal fairness.

Why was May 1967 so different to October 2023? What is the story that unwraps these polarising differences across 56 years?

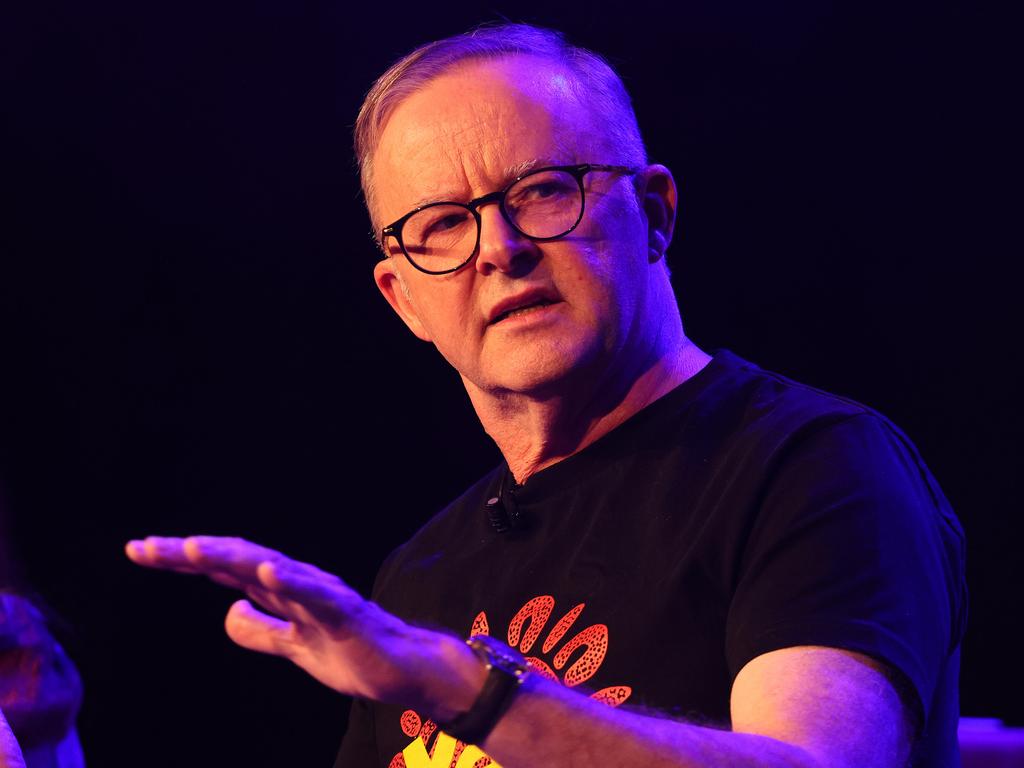

Even if the voice is carried next weekend, the margin will be razor thin, nothing like that marvellous 90.8 per cent.

There are many explanations but race lies in the foreground. The narrative cannot be unwrapped without addressing the transforming story of race in Australia – it constitutes over half a century a near revolution set against a different world and changing values.

The political context is vital. The 1967 referendum was proposed by the Coalition government led by Holt. The actual changes were modest – if Anthony Albanese thinks the voice is a modest proposal he should check out the real thing circa 1967.

The modesty of the proposal delivered bipartisanship. A formal No case was never drafted. The referendum transcended politics. The Holt government did not spearhead the campaign. The key to the referendum’s success was the fusion of two ideas – that Aboriginal people deserved a “fair go” and that nothing much would change.

There was no threat to the established order but the public felt the right thing was done by its conscience. It was the ultimate exercise in safe change and feeling good. There were two alterations to the Constitution: allowing Aboriginal people to be counted in reckoning the population and extending the provision that the federal government could make laws for any race to include the Aboriginal people.

Announcing the campaign, Holt said the first existing provision was “completely out of harmony with our national attitudes” while the second existing provision was seen to be discriminatory. Holt’s biographer, Tom Frame, said: “In Holt’s mind – and many of his contemporaries felt the same – Aborigines could participate in Australia’s public life but they had to think and act like Europeans.” Before his retirement Robert Menzies told parliament that Aboriginal people should not be “treated as a race apart”. Assimilation was the vibe.

The government never saw the referendum as the start of a reform agenda – just the opposite. Holt knew almost nothing about the Aboriginal people. His government was lukewarm towards the referendum. Holt had no program for legislative change if the referendum passed.

Cabinet documents reveal the government’s aim was to correct “misleading” impressions about racial discrimination, bolster the country’s international reputation and prove Australia wasn’t racist.

The government wanted to keep the status quo. Its real priority was the associated referendum – to break the nexus between the Senate and the House of Representatives – though that proposal was defeated.

Yet the cultural edifice surrounding the 1967 referendum has dwarfed its substance. The mythology about the referendum is magnificent yet misleading. Its historians, Bain Attwood and Andrew Marcus, say: “Over the years it has been popularly claimed that the referendum gave Aboriginal people the vote, granted equal citizenship, repealed racially discriminatory laws, transferred Aboriginal affairs from the states to the commonwealth, or that it did all of these things.

“Indeed, this was how the referendum was represented at the time. Yet a reading of the Constitution would suggest that the changes endorsed in the referendum could have had none of these outcomes.” As the years advanced the fiction that 1967 had been a transforming moment became a political reality.

The political driving force for the Aboriginal people was the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders that, in effect, hijacked the referendum and said a Yes vote meant Aborigines would be regarded “as Australian citizens by right”. This was astute. It intensified the stakes but never frightened the public.

In his penetrating July 2023 Australian Book Review article and podcast reflecting on the 1967 referendum, Attwood has offered deep insights on community attitudes. He said: “The campaigners presented their case in such a way that white Australians could feel that by voting Yes they were bestowing on Aboriginal people the same rights and privileges they had and were thereby enabling them to become Australians just like them. In voting Yes, they were able to feel proud rather than ashamed that the changes they voted for were badly needed.”

This was the racial mindset that delivered the 90 per cent vote. Yes campaigners were rejecting the idea of racial differences. Attwood said: “The white campaigners held that Aboriginal people would be better off if all Australians could largely transcend a sense of being racially or culturally different. Aboriginal people were to be assimilated into a common Australian culture. While they might remain different, their cultural difference was not considered to be terribly significant.”

The demand was for “equal rights” – that’s what the notion of citizenship meant. It was the sheer power of the Australian ethic of equality, regardless of race, that drove the result. Labor’s future Aboriginal affairs minister, Gordon Bryant, said while many Australians knew little about Aboriginal people they had the idea “based on a good Australian tradition that the Aboriginal people of this country had not had a fair go”.

Of course, some Aboriginal leaders wanted more and aspired to special rights. However, special rights in 1967 were not seen as group rights but as individual rights.

Nothing could be more different between 1967 and 2023. The referendum today is put by a Labor government, the Prime Minister leads the campaign, there is no bipartisanship, the Coalition is formally opposed, the issue is riven by partisan politics, Aboriginal Australians spearhead both the Yes and No sides, the idea of a voice is founded in the belief of group special rights in the Constitution and these special rights are seen to be indispensable in addressing Aboriginal disadvantage.

Addressing contemporary attitudes towards race, Attwood said: “Unlike in 1967, racial difference – or what some might prefer to call cultural difference – is regarded as something to be embraced, nurtured, celebrated. To be different and to be regarded as different is, in large part, no longer seen by most people as something bad but as something good.”

As Attwood said, the rights now sought, and having been sought for some time, are not the rights of all Australians irrespective of their differences. They are not equal rights “but Indigenous rights; that is, the rights that only Indigenous people can claim on the basis of the fact that they trace at least some of their ancestry to the original or Aboriginal peoples of this land”.

This leads directly to the power and the dispute about the voice.

What is now being proposed? He said: “First, that Aboriginal people be recognised as different from other Australians on the basis that they are the country’s first peoples. Second, that a voice to both the legislative and executive wings of government be formally created for Aboriginal people that no other racial or ethnic group in Australia enjoys (but which practically all such groups already have in an informal sense).

“Furthermore, what is being sought by Aboriginal people rests on a history that is characterised as inherently shameful, involving as it does the legacies of the dispossession, displacement, decimation, deprivation and discrimination that the nation’s first peoples have suffered. In short, the profound shifts that have taken place in thinking about race, rights and history in Australia in the decades since 1967 mean that campaigning for a Yes vote is an infinitely more difficult task than it was 56 years ago.”

There is a further subtle but decisive difference. The Yes case for the 2023 referendum is that only a representative Indigenous constitutional body can successfully address the condition of Aboriginal disadvantage. To say this is a big claim underestimates its significance.

It is a new leap in the old debate about listening to various Indigenous groups and institutions. Yet tying the improvement of the Indigenous peoples to the creation of a representative institution in the Constitution is a contentious and risky proposition. Do we really believe that improving the lot of Aboriginal people depends upon creating a new representative body? This case needs to be made, not just asserted; yet the Yes case has struggled throughout to make this connecting argument to an unconvinced public.

The further extraordinary claim now being made by some Yes supporters is that the 2023 referendum has nothing to do with race. Indeed, this emerges as the latest tactical response by the Yes case to confront the referendum’s apparently insuperable problem: public reservations about how far the idea of special racial and cultural rights should be pushed in Australia.

The entire No case rests upon this reservation.

For several decades the issue of the Indigenous people has been tied to the quest for racial justice and racial non-discrimination. Pretending the voice has nothing to do with race is a sophistry lost on most Australians. There are two truths about the voice – it is about the First Nations people and it is about race.

There is no question that the Australian public has come a long way on this issue of special rights for Indigenous people. The Coalition parties have continually tried to draw the lines, only to be defeated. It is a lesson they need to remember in coming weeks. While disputed at the time, there is now largely bipartisan acceptance of land rights, native title, the apology and the need for special provisions and institutions for Aboriginal people. Defeat for the voice referendum won’t change this polity.

In a sense the 1967 referendum helped to seed this political revolution. With the benefit of 50 plus years of historical perspective the 1967 vote unleashed over time rising expectations and demands from Aboriginal people.

Far from offering any basis on which to settle Aboriginal policy, the 1967 referendum guaranteed the real and inevitable struggle was about to begin.

Holt had taken modest executive action – creating a Council of Aboriginal Affairs under HC Coombs as chairman – but Aboriginal leaders denounced the government for its moral failure and policy timidity.

Within politics, the action came from Labor. In typical fashion Whitlam branded the referendum a mandate on which to “promote health, training, employment and land rights”. He attacked the Holt, Gorton and McMahon governments, saying they failed conspicuously to act on this mandate. In his 1972 policy speech, Whitlam said: “Australia’s treatment of her Aboriginal people will be the thing upon which the rest of the world will judge Australia and Australians.”

The late 1960s and early ’70s were a time of hope and optimism. Expectations about Aboriginal rights rose on this tide. The Whitlam government transformed the debate about Aboriginal issues – it created a ministry for Aboriginal affairs, pledged a system of land rights and passed the Racial Discrimination Act of 1975. The Fraser government made much of this bipartisanship.

What mattered in the end was not the strict letter of the 1967 constitutional changes; it was the political momentum they helped to generate in an Australia where views about race began to change. Here was the paradox of 1967: minor constitutional alternation but substantial policy dividend over time.

It is a story now forgotten; witness the contrasting 2023 campaign to secure major change through the immensely difficult pathway of constitutional amendment.

Attwood and Marcus are surely correct in arguing the 1967 legacy was bestowing “upon the Whitlam and subsequent governments the moral authority required to expand the commonwealth’s role in Aboriginal affairs and implement a major program of reform”.

There was, however, another legacy. Riding on the back of 1967 another idea took hold: that the Aboriginal quest must transcend the bid for mere “equal rights” and should extend to special rights based on the historical legacy. This eventually would evolve into an irresistible political and moral movement, much flowing from the High Court’s 1992 Mabo judgment that changed race relations and altered power relations between black and white.

Paul Keating said the High Court “rejected a lie and acknowledged a truth” and, after a tortuous negotiation, legislated the Native Title Act.

In his second Boyer Lecture last year Noel Pearson offered a framing for the current setting of Indigenous rights. “The cause of recognition is not a separatist cause,” Pearson said. He said there should be recognition of the “special status” of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people within a unified country. Invoking both Whitlam and John Howard, Pearson said recognition was “about the rightful but not separate” place of Indigenous Australians.

His framing is surely correct.

The real issue today is how this framing is interpreted and expressed. Pearson hoped the voice would fit that framing, but at least half the country seems to disagree. We like to think Indigenous rights should be built on bipartisan foundations. That’s desirable but it’s often not the history – such rights often emerge only after a partisan conflict.

Any defeat for the voice is just a defeat for the voice. It is not a defeat for the idea of special rights for the Indigenous people. This idea is entrenched in our polity. It has evolved over decades and it won’t be extinguished. The worst mistake the Coalition parties could make would be to interpret any defeat of the voice to mean a rejection of special rights for Indigenous people. Note, for example, prominent No campaigner Nyunggai Warren Mundine is a supporter of treaties.

The 1967 referendum reflected a more innocent, less political age. It came on the cusp of great changes and, indeed, was a symptom of the coming changes. It tells of a community of goodwill towards Aboriginal Australia yet of astonishing naivety. In truth, despite what you are told about the 1960s, the public was still politically conservative.

As the demand for special Aboriginal rights intensified, the divisions that opened up in Australia were inevitable. The issue now before us is how to give expression to these legitimate requests from Aboriginal Australians. If the voice is defeated, that will represent an example of over-reach and a serious misjudgment of the wider Australian community. But the quest will continue.

In 1967 Australians were fighting in Vietnam, Gough Whitlam became leader of the Labor Party, a new prime minister, Harold Holt, was feeling his way – and on May 27 Australians, in an event unmatched before or since, voted 90.8 per cent to amend the Constitution to benefit Aboriginal people.