Noel Pearson’s pitch for voting Yes, his long journey to the Indigenous voice to parliament and a rightful place for Indigenous Australians

Making a final pitch for Yes, Noel Pearson talks candidly about the personal toll the campaign has taken as his life’s work faces its biggest test.

As the campaign for recognition of Indigenous Australians in the Constitution by establishing an advisory body to parliament and government enters its final week, Noel Pearson remains optimistic that the referendum will be carried.

“I believe there’s every chance we are going to do this because it just doesn’t make sense for Australians to say No,” he told Inquirer over a nearly three-hour discussion this week in Sydney. “We have one shot at this. There is only one chance for us to get this right, which is why I’ve opposed just symbolic recognition on its own. There has got to be a substantive dimension to the reform.”

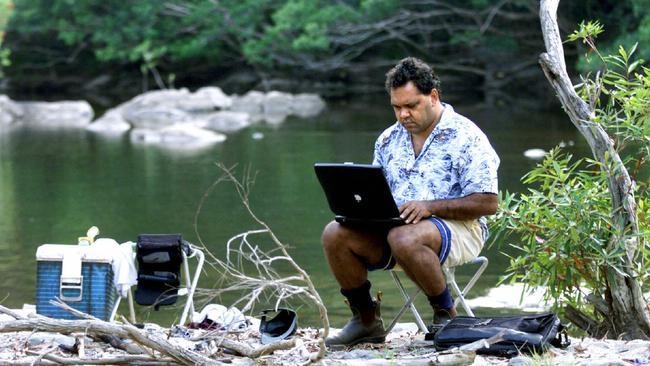

For Pearson, raised in the Guugu Yimithirr community of Cape York and founder of the Cape York Institute, it has been a long journey. For more than 30 years he has engaged with prime ministers, ministers, bureaucrats and advisers on issues from native title and school education to welfare reform and ending violence and substance abuse.

As the principal architect of the voice, and the most persuasive advocate, he has been in demand to speak to groups small and large around Australia. He has addressed town hall meetings, churches and civic groups, and has been interviewed on radio and television.

This is the nation’s finest orator making the case for the voice writ large, animated, powerful, in full flight. He was made for this. But he can rarely walk down a street or through an airport, catch a ride or check into a hotel without being stopped for a conversation.

The image of Pearson, clad in a black or brown fedora-style hat, bright white or black T-shirt emblazoned with “YES” wrapped in a suit jacket, with jeans or chinos and boots, is unmissable. These one-on-one dialogues require a different advocacy.

He can marshal 100 different arguments in support of the voice to suit his interlocutor, as though flicking through index cards to find the right one that might turn a No vote into Yes. Pearson says he can tell, almost instantly, if he is adding to the Yes tally. It can be reassuring or dispiriting, depending on how the exchange goes.

This unrelenting pace and the pressure of the campaign have taken their toll. Over a meal in a nearly empty restaurant and then a late-night cup of tea in a hotel lobby, Pearson looks tired. His mind often wanders, turning over ideas and searching for the right words, until his eyes sharpen with a determined look and proselytising zeal as he focuses to make an argument.

There is a melancholy about Pearson that balances his hope for, and optimism in, Australia. I spent a day with him in March, walking the Noosa headland, talking about his life and the looming referendum. Many of the elders he worked with on native title in the 1990s are gone. He lost his sister last year. He instinctively feels his own time is running out as his life’s work faces its biggest test.

“If we are repudiated, then we are going to have to wear responsibility for that,” Pearson says of the thoughts now bearing down on him. “I’m going to have to. I will forever wear responsibility for having cajoled and encouraged my people to put faith in their fellow Australians. And I don’t know how I’m going to handle that.

“I will have asked them to put the kind of faith that is articulated, that is captured, in the Uluru statement and it has been all for nothing. So that’s on my mind. My family, too; I’ve put them through this, right? You are given so much unqualified support by family, immediate and back in Hope Vale, and my whole community. You know, they are with me on this.”

In his 2014 Quarterly Essay, A Rightful Place, Pearson outlined how the Constitution could be amended to give Indigenous Australians a say in laws and policies that affect them, and to enable them to take greater responsibility without undermining parliament or risking litigation.

But he reveals to Inquirer that his thinking began much earlier and shared a PowerPoint presentation, titled Playbook, outlining a high-level strategy for constitutional recognition that included a “structural dimension” rather than removing discriminatory provisions or including preambular words in 2011. “This can’t just be symbolic acknowledgment,” Pearson explained, flicking through the 2011 presentation. “The crucial piece here is that it will result in structural reform.”

The pathway to constitutional recognition that was both symbolic and practical, enabling a reckoning with the past that fostered reconciliation for the future, and a mechanism to improve the lives of Indigenous Australians, culminated in the Uluru Statement from the Heart in 2017.

This eloquent, poignant and generous one-page statement asked all Australians to join them in a spirit of reconciliation and support constitutional recognition by establishing an advisory body known as the voice, which would provide advice to parliament and government on matters that affected Indigenous Australians.

Recognition through a voice in the Constitution is making “a concrete promise” to reconcile the nation and include Indigenous Australians in policy discussions about matters that affect them, Pearson says. Putting it in the Constitution – the so-called big law – is essential. “Aboriginal Australia has reached out to make peace about the past,” he argues.

“We want to be part of Australia. We want to be part of the Constitution. We have been left out of it for a long time and now is our chance as a country for inclusion and for us to put victimhood behind us … the formula is a rightful but not separate place in Australia.” That proposal, now before the Australian people, would change the interface between Indigenous Australians and policymakers. It would structure a process of listening and learning, itself an act of recognition of 60,000 years as the First Nations on this continent, to address the entrenched disadvantage in education, health, employment, housing, justice and safety.

The voice will enable accountability, responsibility and transparency from Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

This has always been part of Pearson’s pitch for constitutional recognition through the voice advisory body. The annual Closing the Gap report will be, he argues, a report card on progress.

“The principle that permeates Indigenous Australia is the idea that government has got to solve Aboriginal problems and so the service delivery of the state is the source of salvation for Indigenous people,” Pearson says.

“We have got to permeate the whole Aboriginal scene with the policy of empowerment. In other words, we have got to ask of every dollar and every program: is this contributing to the empowerment of Indigenous people?”

He insists the voice is not about dividing Australians by race.

“The people who were here prior to 1788 were of the human race, same as the people who came afterwards,” Pearson says. “It is just that there were people here who were indigenous to Australia. They had a connection to the country that preceded the Europeans. That’s a question of indigeneity, not a question of race.”

While there are design principles for how the voice would be established and how it would operate, it will be up to the parliament to determine its composition, functions and procedures. The Constitution only establishes a head of power. It does not fundamentally change the structure of government or challenge the authority of parliament.

“The detail is a responsibility of parliament,” Pearson explains. He concedes the referendum “is now under severe challenge” with the No camp, led principally by Nyunggai Warren Mundine and Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, making headway in turning people against the referendum. But he says they have no alternative plan for improving Indigenous lives.

“No is just an act of destruction,” he says. “It is not a positive action for an alternative path.”

Those behind the No campaign, Pearson argues, are the Institute of Public Affairs and the Centre for Independent Studies. “They are the real No campaign,” Pearson insists. “They have mobilised Warren and Jacinta, very understandably, because … those two think tanks couldn’t carry a No campaign.”

Asked if he doubts their integrity in believing in and fighting for the No side, Pearson responds by saying Price “probably always will have held these views about a structure like the voice” and “believes the No case”. And Mundine? “He’s occupied every position on the spectrum,” Pearson says.

Yet Pearson acknowledges the three of them are “in furious agreement” about the problems faced by Indigenous communities.

“I’m probably more in agreement with them than I am with my allies on the progressive side,” he says. “They just don’t have solutions to those problems.”

If the referendum is carried, Pearson will not serve on the voice. “I’ve never held an elected office other than my first stint on my local community council when I was 23 years old,” he says. “I’d prefer other people to serve. I’d certainly want to play a role in advising the leadership.” He adds: “I’m in the business of natural leadership and natural leaders need ideas and they need to bring people with them. Whereas elected and structural and formal leadership, I’ve got very little interest in that.”

The polls spell doom for the referendum. But polls can be wrong. There is strong support from those under 50 and strong opposition from those over 50. Pearson cannot reconcile the polls with his experience on the campaign trail. The strongest support he has encountered is from non-Indigenous Australians over 55. “There is a lot of goodwill and anxiety about the situation of Indigenous people and the need to do this reform,” he says.

Throughout the campaign, Pearson has been reluctant to contemplate a No vote and what it would mean for the country, its people and the reconciliation agenda. But, pressed, he argues that Australia will be diminished and the reconciliation process will be extinguished.

“We will be in this peculiar situation where people who have been here for 235 years will have rejected the request for recognition by people who have been here for 60,000 years,” he says.

“I think there will be shame attached to that.”

And, if Australia votes Yes? “We are going to be enormously proud of what we’ve done,” Pearson answers. “We will finally have shed the kind of existential bloody hang-ups we have had in this country for too long. And the existential hang-up is this: if we recognise these black fellows, what happens to us?

“It was always the psychological case against recognition: that our legitimacy could not survive recognising their legitimacy … when we finally do it with this vote, we are going to realise this existential angst that we have had is put behind us. That’s history.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout