Robert French: Indigenous voice to parliament’s access to executive government can be limited

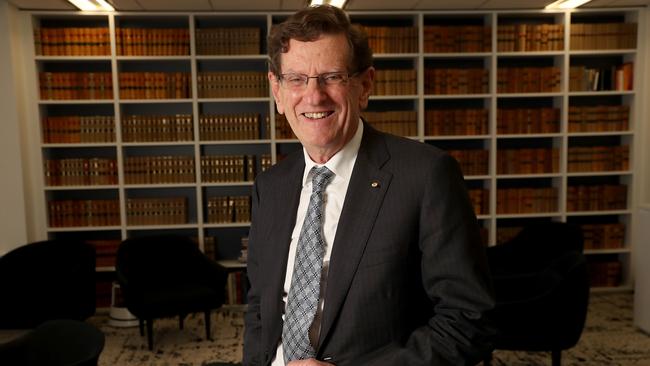

Former High Court chief justice Robert French has launched a key defence of the voice ahead of the referendum, saying parliament can limit its access to executive government.

Parliament could limit the voice’s engagement with executive government by ensuring it does not enjoy unfettered access to public officials, cabinet ministers or the governor-general, according to a key defence of the advisory body made by one of the nation’s eminent legal thinkers.

Former High Court chief justice Robert French will on Friday argue that the parliament would retain its supremacy and have the power to place limitations on how the voice engaged with executive government under the third clause in the government’s proposed constitutional amendment.

“Parliament can determine to whom and how representations can be made,” he said.

The No campaign and constitutional conservatives have warned of possible far-reaching consequences arising from the ability of the voice to make representations to executive government, with Peter Dutton arguing it could “disrupt our system of democracy”.

In an address to the National Press Club in Canberra on Friday, Mr French will seek to defang these claims by saying that the third clause of the proposed constitutional amendment - section 129 (iii) - could “prescribe the means and mechanisms for representations to made to the executive government”.

“Representations might, for example, have to be directed to the relevant minister or a body nominated by the relevant minister, such as the National Indigenous Australians Agency. The parliament can determine to whom and how representations can be made,” he will say.

“It is not required to allow representations to be made to any person or authority engaged in the work of the executive government, which could cover a spectrum from the governor-general to ministers of the crown and a vast array of public officials.”

The ability of the proposed advisory body to make representations across the spectrum of executive government was cited as a key advantage by proponents of the referendum, including by Megan Davis - an architect of the Uluru Statement from the Heart and one of the six members of the government’s working group that negotiated the final wording of the constitutional amendment.

Writing in The Australian in April, Professor Davis and fellow constitutional law expert at the University of NSW Gabrielle Appleby said the voice would “be able to speak to all parts of the government, including the cabinet, ministers, public servants, and independent statutory offices and agencies – such as the Reserve Bank, as well as a wide array of other agencies including, to name a few, Centrelink, the Great Barrier Marine Park Authority and the Ombudsman – on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.”

In his address on Friday, Mr French will argue that it is “improbable” that a failure to consider representations made by the voice would result in the invalidation of government decisions, although he conceded it was possible that “someone, some day will want to litigate a matter relating to the voice”.

“The risk of any such litigation succeeding and imposing any burdensome duties, or any duties at all, upon the executive government of the commonwealth is low when set against the potential benefits,” he will say.

He condemned the key battle cry of the No campaign – ‘If you don’t know, vote No’ - as a “poor shadow of the spirit which drew up our Constitution”.

“It invites us to a resentful, uninquiring passivity. Australians, whether they vote yes or no, are better than that,” he will say.

He will also reject arguments that the voice is a race-based institution, saying it was instead aimed at recognising the original inhabitants of the land prior to European settlement; at federation, there were “hundreds of different Aboriginal languages spoken across Australia”.

“The unifying characteristic which underpins the voice is their history as our First Peoples,” Mr French will say. “It would not matter whether Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were one race or dozens of different races.”

Anthony Albanese on Thursday told a gathering of faith leaders that he was doing “whatever I can” to achieve a Yes result on October 14, likening the mission of migrants who came to Australia in search of a better life to the objective of the voice in delivering better outcomes for Indigenous Australians.

Speaking to Islamic, Hindu, Buddhist, Christian, Jewish and Sikh leaders, the Prime Minister confirmed at a roundtable in Sydney’s inner-city Glebe that he would travel to Uluru early next week, from where the Uluru Statement from the Heart was first read out.

“I am greatly encouraged by the very broad spectrum of faith groups that have supported the voice. I’m not aware of any who have any disagreement with advocating a Yes vote, and that says a lot about the nature of the request,” he said

“This is such a gracious request ... It is for a non-binding advisory committee to be able to make representations on matters that affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people ... And we will get better outcomes.”

Rejecting characterisations of the voice as a third chamber of parliament, Mr French will say on Friday that the parliament and executive government would not be bound by representations from the advisory body.

“The establishment of the voice by popular vote would generate a democratic mandate to respect those representations and to take them into account.

“That does not translate into a mandate enforceable by the courts,” he will say.

He will also reject claims the voice would amount to “another Canberra bureaucracy”, saying it would not be “a collection of officials” and its members would be “selected from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies across the nation”.

“Terms such as ‘Canberra bureaucracy’ weaponise words by distorting their meaning in a way which is unhappily characteristic of public, political discourse today,” he will say.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout