Benefits of Indigenous voice to parliament far outweigh risks, writes former chief justice Robert French

We can draft a constitution and our laws to minimise uncertainty but can never eliminate it. In the end we accept that judgment on important matters often involves weighing benefit against risk.

The proposed amendment to the Constitution to provide for an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice to parliament and the executive offers the opportunity for great benefits. The first of these is the recognition of our First Peoples in our national Constitution.

Their recognition, which the creation of the voice will establish, is not recognition of a race. It is recognition of their special historical status as the first occupiers of our continent. They are the bearers of its first great history stretching back tens of thousands of years. They are also the bearers of a rich culture expressed in dreaming stories, art, song and ceremony of which all Australians can be proud.

The second benefit is the creation of a constitutionally supported means of communicating to parliament and the executive advice based on the experience and perspectives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples across Australia. The inadequacy of our laws and practices to respond to the immense social justice challenge posed by acute inequity at many levels of a significant number of Indigenous peoples poses a national challenge.

The voice is intended to bring together those experiences and perspectives to try to influence change in our laws and practices for the better. That is not just a benefit for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It is a benefit to the whole of the Australian people.

There will inevitably be Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who disagree with particular positions advanced by the voice. Their criticism and alternative views can still be advanced to parliament and the government, as can those of any Australian.

The voice will derive its moral authority from its constitutional status. That does not require that it have legal authority to bind the parliament or executive to give effect to its representations. The risk that advice from the voice could have that effect is non-existent.

Nor can the voice bind the parliament to have regard to its representations before a law is enacted. That would be a limitation on the lawmaking power of parliament which, if intended, would have to be spelt out in the Constitution. The amendment does not do that. The implication is not open.

The remaining area of debated risk is that the executive might be legally required to have regard to representations made to it. Absent a law of the parliament to that effect, that would have to be a constitutional implication. If such an implication was drawn it could apply only to actual specific exercises of statutory or non-statutory executive power. It could not apply to the vast array of matters on which representations might be made to the executive and that on any view would not be amenable to judicial review. That includes representations about desirable changes to the law and high-level policies and practices that are not capable of attracting judicial review. For that reason it is improbable that such an implication would be drawn about representations relating to the exercise of specific statutory or non-statutory executive powers.

It cannot be said that the risk is non-existent. And if it eventuated, it might mean that in certain decisions an executive decision-maker would have to consider a representation before making the decision to which it relates. That is a far cry from being required to comply with the proposals or advice contained in the representation.

It is critical that the voice be able to make representations to the executive government.

The laws that parliament makes and that affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are of great importance. But it is their application by the executive that determines their impact. There is a very large body of “soft law”: policies, practices, guidelines and manuals. For people on the receiving end of those policies they are the law in action. Effective executive government in this difficult area requires informed advice, which the voice should be able to provide. That does not mean the advice can be legally binding, nor that there should be a legal obligation to have regard to it.

The proposed amendment to paragraph three, allowing the parliament to make laws about the legal effect of representations, may reduce the risk of an implication that the executive would be legally bound to take them into account. Even if it eventuated it would not outweigh the immense potential benefit to the Australian people from the voice proposal.

It is useful to remember the words of Sir Samuel Griffith, a principal architect of the Australian Constitution and the first chief justice of Australia.

At the 1891 Constitutional Convention he referred to those who were afraid of launching new things and said: “But when was ever a great thing achieved without risking something.”

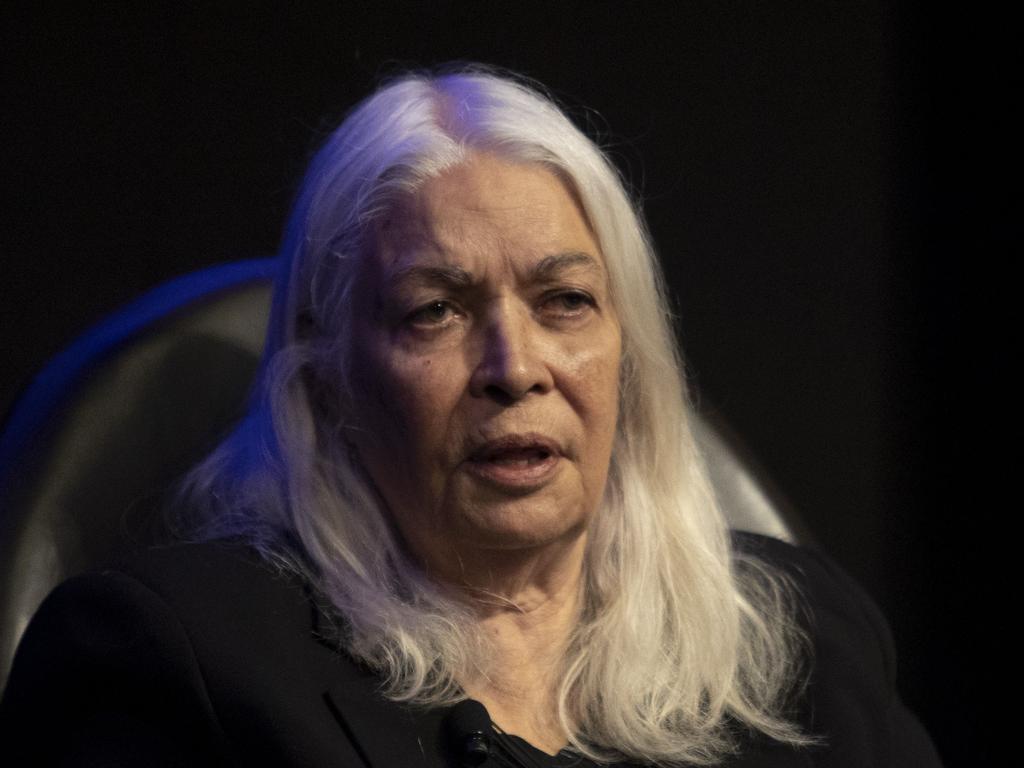

Robert French served as the 12th chief justice of Australia from 2008 to 2017.

Absolute certainty in human affairs is no more attainable than absolute certainty in science.