Indigenous voice to parliament: Why time is running out for Noel Pearson, and reconciliation

One he characterises as ‘worthless’, another as ‘completely without principle’, and in a third he ‘couldn’t detect any particular commitment to Indigenous affairs’.

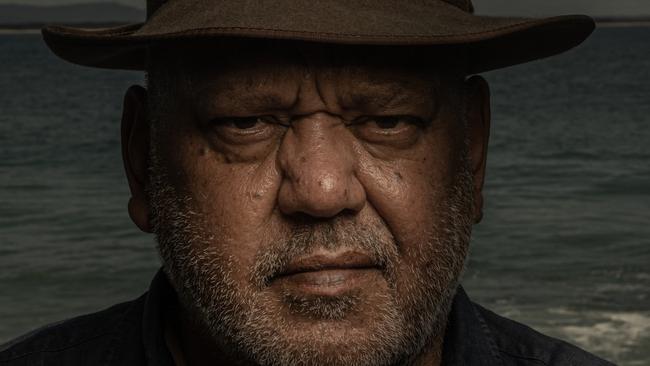

Walking along the winding uphill path of the Noosa headland in Kabi Kabi country, catching glimpses of the sweeping ocean views between the lush bush greenery, Noel Pearson talks about his journey from a Lutheran Mission in Hope Vale to the corridors of power in Canberra, seeking justice and opportunity for his people, and a nation reconciled with its past.

Thirty years ago, Pearson burst into national prominence as a young lawyer representing the Cape York Land Council in negotiations with Paul Keating about formulating a legislative response to the High Court’s Mabo decision. At age 27, Pearson was one of 21 Indigenous leaders who met with Keating in the cabinet room in April 1993. Six months later, after protracted negotiations and a rollercoaster of emotions, a landmark agreement was reached. The Native Title Act 1993 became law after a lengthy Senate debate in December that year.

“I learned that in order to secure wins, we needed leadership and we needed to have the courage to make decisions,” Pearson tells The Weekend Australian Magazine.

“Most people don’t understand the extent to which native title was not only preserved but enhanced because of the leadership shown by the Aboriginal negotiators in that process, with Lowitja O’Donoghue leading us. I also came to admire Keating and have a taste for how power is exercised. It was literally the year after law school. It was the biggest learning curve of my life.”

Land rights was the first, though unfinished, phase of Pearson’s public advocacy. The second, also ongoing, is his work to address entrenched disadvantage in Indigenous communities by improving education, fostering parental responsibility, and ending welfare dependency and substance abuse. With research, innovation and experimentation, it is what he calls the search for the radical centre in public policy, taking ideas from the left and right. The third phase is the reconciliation and recognition agenda that has culminated in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

As both architect and advocate for the Indigenous voice to parliament, Pearson sees the forthcoming constitutional referendum as a test for a nation that has long struggled to achieve lasting reconciliation with the First Australians. It is not about guilt or atonement but about recognition. They are two sides of the same coin: recognition is reconciliation. It is both symbolic and practical, representational and substantial, about the past and the future. The referendum would establish a body that “may” make representations to executive government and Parliament “on matters relating to” Indigenous Australians. The Parliament will determine the “composition, functions, powers and procedures” of the Voice. It will have no power to delay or veto any decision.

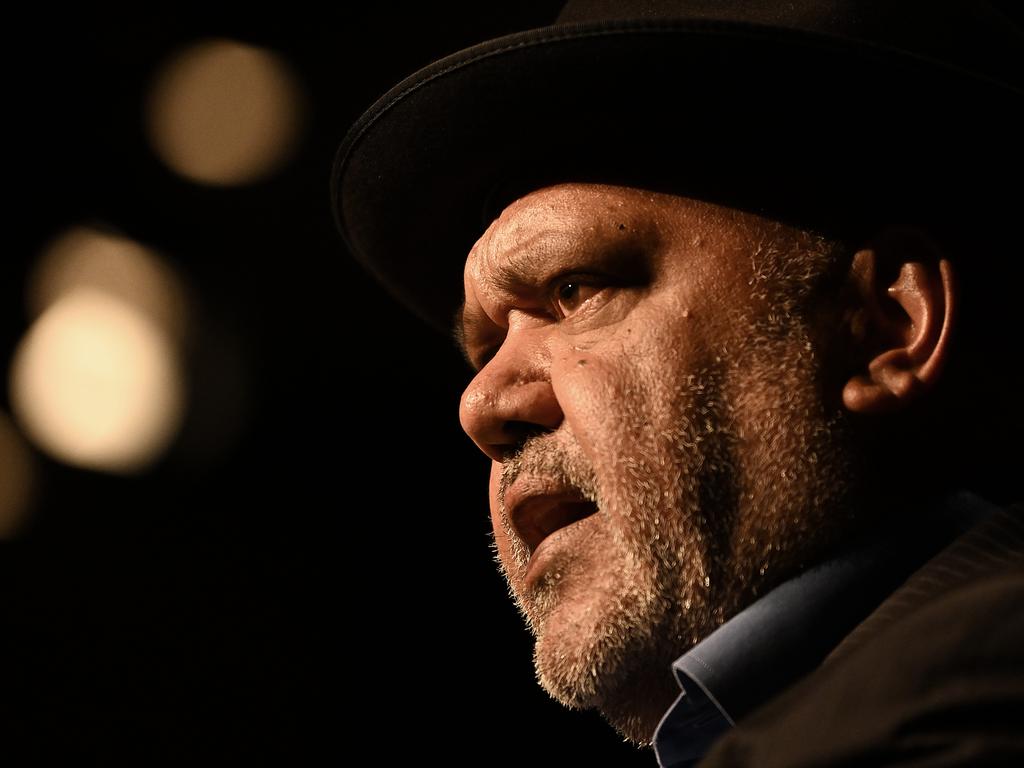

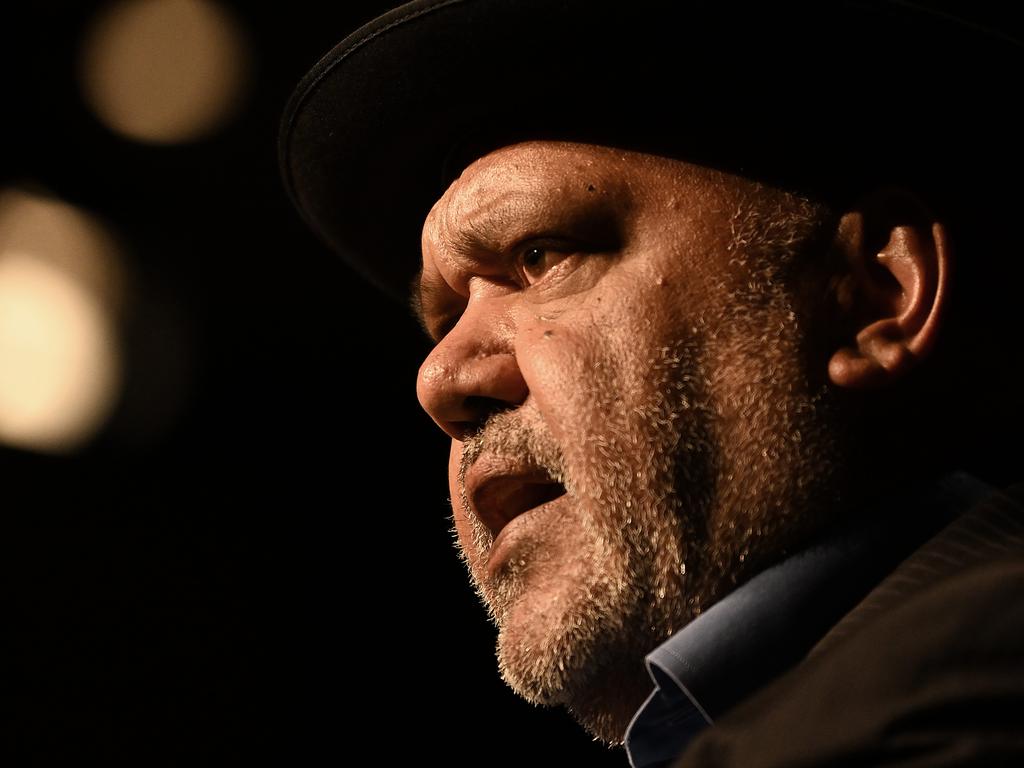

Pearson is lit from within. You feel it when in his presence. He is as compelling and convincing one-on-one, walking along a bush track or sitting in a restaurant among the tourists, as he is when commanding the powers of oratory to swell hearts and change minds from a public stage. In an age where the art of speech is almost a redundant craft, Australia has no finer orator. In interviews, Pearson’s voice carries an authority and force that turns heads with phrases that linger in the air. His coolness and detachment, which some interpret as arrogance, cloaks a deeply thinking mind. Beneath the often tranquil exterior bubbles a righteous indignation.

Some Australians, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, do not trust him. Yet he is a loner and collaborator, leader and team-player, pathbreaker and peacemaker. He can be prickly, aroused to furious anger with searing judgments all the while preaching the wisdom of travelling the “high road” in debate, such as when he lashed Peter Dutton for his Judas-like “betrayal” over the Voice and branding him as the “undertaker” of the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

The Voice, endorsed in the Uluru Statement, has been a Pearson project for a decade. In his Quarterly Essay,

A Rightful Place (2014), Pearson first made the case for amending the Constitution “to make provision for indigenous people to be heard in indigenous affairs” to ensure they “get a fair say in laws and policies” but “without compromising the supremacy of parliament”. It would enable them to “take more responsibility for our lives within the democratic institutions already established and without handing power to judges”.

(2014), Pearson first made the case for amending the Constitution “to make provision for indigenous people to be heard in indigenous affairs” to ensure they “get a fair say in laws and policies” but “without compromising the supremacy of parliament”. It would enable them to “take more responsibility for our lives within the democratic institutions already established and without handing power to judges”.

The Voice, as now formally proposed, has several authors. As we walk beneath the hot autumn sun, Pearson pays tribute to Megan Davis, Pat Anderson and Shireen Morris, Marcia Langton and Tom Calma, Pat Dodson, Linda Burney, Ken Wyatt, and others. He joins them in marshalling an unrivalled command of language, packed with emotional and intellectual firepower, to win public support.

Peering into the soul of the nation, Pearson has articulated the notion of a layered Australian identity with three strands of an “epic” story: “our ancient heritage, our British inheritance and our multicultural triumph”. This is another attempt by Pearson to bind a nation. Recognition, he argues, is essential in having a unifying national narrative where everybody is counted and belongs. It is not about pitting one heritage against another but about acknowledgment, respect and harmony. It is why he also advocates a two-day Australia Day commemoration that recognises the Australia before conquest on January 25 and after on January 26, straddling two sovereignties. It is about bringing the various threads of the Australian story into one unifying tapestry. It is Pearson as both healer and unifier.

“I’ve learned the distinction between who we are and who we can be,” Pearson explains. “But we need leadership. There has been no shortage of leadership from Indigenous Australia. We show leadership to our own people and we show it to the rest of the country. What we have not seen is leadership from White Australia. Anthony Albanese on election night was the first sign of real leadership since 2007. So only on this last leg have we got prime ministerial leadership.

“If we win this referendum, the country will have changed and we will have turned over a new leaf. And I think Australians are yearning to move to a new chapter.”

–

“I’ve learned the distinction between who we are and who we can be. But we need leadership.”

–

It was Pearson’s idea to walk and talk in Noosa. He moved to Lake Cooroibah, on Noosa’s North Shore, for treatment for cancer in 2012. Pearson has two daughters at school and a son at university, and plans to return home to Cape York when his youngest finishes her schooling.

I first met Pearson about 10 years ago. We have talked and corresponded occasionally since then, and I have interviewed him before. He launched my biography of Paul Keating with an impassioned fire and brimstone speech in 2016. He embraced my daughter and son with a gentleness that remains fixed in my memory. Our two-and-a-half hour walk snaked through the headland, with sweat beading on our faces, cooled only by gushes of wind as we reached a peak. We talked about our work, our families and growing up – Pearson in the Guugu Yimithirr community of Cape York, the oldest continuing culture on Earth, and me in the Sutherland Shire, south of Sydney, which styles itself as “the birthplace of modern Australia”. We ruminated on political leadership and judged those past and present, discussed native title, welfare, education and employment policies, the bottom-up work of the Empowered Communities initiative and the Voice. The discussion continued over lunch, another walk and a two-hour sit-down interview.

On that sandy and rocky track, Pearson would sometimes halt mid-sentence, not to catch his breath or wipe his brow, but to emphasise a point. He recalled explaining the Voice to the Yolngu elders of northeastern Arnhem Land. He held up a power board with six outlets. “The power board is the Voice,” Pearson told them.

“The light that you plug into this power board is different. The Groote Eylandt light is different from the north eastern Arnhem Land light, different from the Tiwi Voice, different from the Cape York Voice, from the Torres Strait Voice. We are going to design our own lights, and yet we all plug into the same power board, which is the Voice. And we plug it into the Constitution. We are given the space to design our own illumination for our region.”

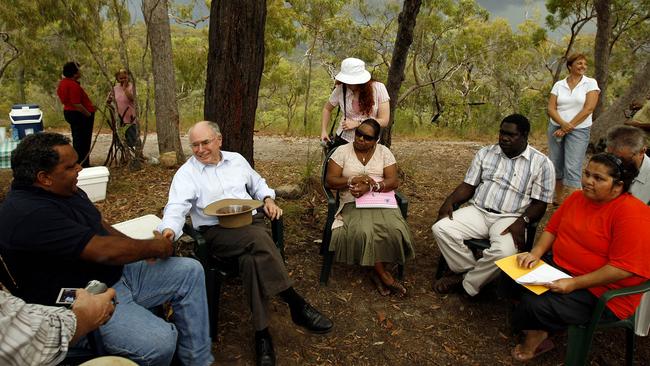

The elders understood. The foundation stone for the Voice was laid in 2007, when John Howard was in his final year as prime minister. Pearson saw an opportunity with Howard, even though the post-Keating years were a wasteland for reconciliation. Pearson met with Howard and wrote him a 6000-word letter urging him to adopt a new “agenda” that included “constitutional recognition” of Indigenous Australians. He told Howard he was a “tier-two prime minister” but could be elevated to “tier-one” if he made reconciliation part of his legacy. Only a conservative leader, Pearson flattered Howard, could do this. Howard proposed a referendum to include a recognition statement in the preamble to the Constitution. “That was a breakthrough,” Pearson reflects. “He was genuinely motivated. But his party never grew after him; they deteriorated.”

Kevin Rudd initially supported Howard’s preamble proposal, but on the eve of the 2007 election it was made a second-term priority for Labor. Pearson viewed Rudd’s refusal to embrace and prioritise Howard’s preambular recognition as a “betrayal”. Pearson was not that surprised, and retained bitter memories of Rudd’s “political cynicism and opportunism” when negotiating the Goss government’s Aboriginal Land Act 1991 and the Keating government’s Native Title Act 1993. (Rudd was chief of staff to Premier Wayne Goss and then director-general of the Cabinet Office.) Rudd never got a second term. Julia Gillard’s government established the Expert Panel on recognition in 2010 and it reported two years later. But little progress was achieved under the Labor government. Asked about Gillard, Pearson says: “I couldn’t really detect any particular commitment to Indigenous affairs.” It was “a lost opportunity” for recognition, he adds.

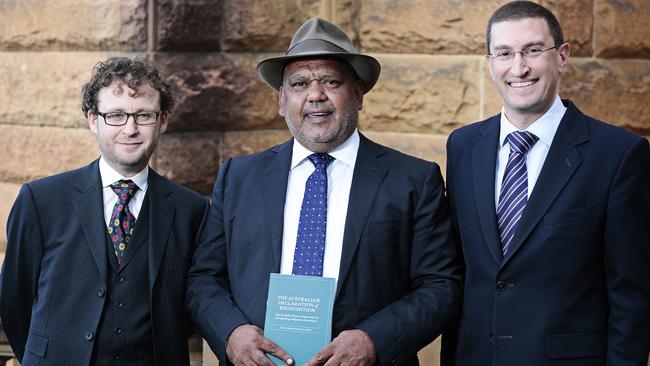

A new Coalition government provided another chance to advance recognition. Pearson again saw an opportunity to win over conservatives. He spent years working with Julian Leeser, Greg Craven and Damien Freeman to develop a conservative model for recognition that was both symbolic and practical to maximise the chances of bipartisan support. Leeser, Craven and Freeman supported a constitutionally enshrined Indigenous body advising government and parliament. Tony Abbott, Pearson insists, also supported a constitutionally enshrined Indigenous advisory body but could not carry his cabinet or party with him. Pearson says Abbott told him: “My conservative colleagues have lost their compassion and have become very hardhearted.”

Again, progress stalled. “He’s completely without principle,” Pearson says of Abbott. “He doesn’t have a consistency and an honesty that a true conservative would have … there was an emptiness there.” Abbott says he has no recollection of these conversations.

–

“I realised there was a connection between work and good family life, and community life. But once welfare took over, the next generation started to crumble.”

–

In 2015, the Referendum Council was established by the Turnbull government. It held 13 Regional Dialogues to consult on constitutional reform. In 2017, the First Nations Constitutional Convention issued the Uluru Statement, which called for the Voice along with a Makarrata commission to oversee treaty-making and a process of truth-telling. Malcolm Turnbull immediately, and wrongly, characterised the Voice as “a third chamber” of Parliament. Pearson recalls being “completely shocked” as Turnbull dismissed the Voice as having “a snowflake’s chance in hell” of succeeding at a meeting of the Referendum Council.

Pearson issues his verdict on Turnbull: “He was worthless to us,” he says. (Turnbull has since changed his mind and supports the referendum.) In 2019, Scott Morrison provided $7 million for a “co-design” process to examine how the Voice could work and set aside $160 million in contingency for a referendum. Pearson says Wyatt’s appointment as the first Indigenous cabinet minister was rightly lauded by Morrison. He judges Wyatt to have done “a very honest job in a very difficult situation” but says he was badly let down by his recalcitrant Coalition colleagues.

“When push came to shove, they didn’t take him seriously at all,” he says. (Wyatt has since resigned from the Liberal Party and will campaign for the referendum.) Pearson met with Dutton several times and was hopeful he would support the Voice, or at least allow Liberal MPs a free vote as they had on the republic referendum and the same sex marriage plebiscite.

Instead, Dutton is now campaigning to defeat the referendum, claiming it would be a “Canberra Voice” with a large “bureaucracy” and spend “billions” of taxpayer funds.

Pearson is wounded by commentary from Leeser and Craven. “Leeser disavowed a concept he was part author of,” he says.

“He played a spoiling role.” While Leeser has resigned from the Opposition front bench and will campaign for the Voice, arguably he sowed confusion and energised opposition.

Professor Anne Twomey drafted Constitutional amendments in 2015 that would provide for a body to advise both the parliament and executive government. While the Opposition objects to executive government being included, it has always been part of the design of the Voice. Any question of justiciability would only relate to whether parliament or government properly considered the advice, not whether they followed it. In other words, that the voice of Indigenous Australians was heard.

Pearson argues that executive government is critical because it would enable input to be given in forming policies, programs and legislation. Requiring ministers and public servants to consult with a Voice would have kept the NT alcohol bans in place, he argues.

It is about redesigning the “interface” between Indigenous citizens and decision-makers. He points to the Empowered Communities initiative, where Indigenous communities and governments already work together in 10 remote, regional and rural areas across Australia.

“The practical day-to-day business concerns the executive government,” Pearson explains.

“Which Australian would not be sympathetic to the bureaucracy at least considering the views of Aboriginal citizens?” Moreover, it is about Indigenous Australians taking responsibility. The Closing the Gap Annual Report, he says, will be a scorecard of both the government and the Voice.

The Mission opened up an opportunity for Pearson to attend St Peters Lutheran College in Brisbane. After school, he was eager “to escape Queensland” given the stultifying politics of the 1980s, and his best mate suggested he join him at Sydney University.

When he engaged in the Mabo and Wik negotiations, fresh from law school, he was in his 20s and then his 30s, working with elders in their 70s and 80s. He promised to reclaim their land and rebuild their society by arresting social deterioration, and providing education and economic opportunities. It has been a long struggle that has taken a toll.

“I had lots of friends when I started and I have few friends now,” Pearson says.

“From the very moment I started working with them, they would die. One would die, then another one, then another one.” But the work went on. “I was convinced that welfare dependency was the killer and we didn’t have a place in the economy anymore,” he says.

“I realised there was a connection between work and good family life, and community life. But once welfare took over, the next generation started to crumble.”

He developed policies and programs to end the “passivity” caused by welfare in the hope that it would promote responsibility and create agency. The search for the radical centre has led to Pearson-led initiatives such as the Family Responsibilities Commission and Good to Great Schools Australia in Cape York and elsewhere, and it guides his next project: a job guarantee initiative. The Cape York Welfare Reform Trial saw elders intervene to withhold welfare payments from parents who failed to address the truancy of their children.

The interventionist model of income management saw increased referrals to support services and law enforcement agencies, and handed responsibility to communities. Pearson proposed a job guarantee in his book Mission

(2021) and in his third Boyer Lecture (2022). It would offer government-funded jobs to the unemployed paid at the minimum wage.

In 1998 and 2001, Pearson had the chance to become a federal Labor MP. With Keating’s support, paths were being cleared for him to make the leap into politics. He was talked about as possibly the first Indigenous prime minister. There were discussions about federal seats in Sydney, Brisbane and Canberra, and a Senate vacancy in NSW. He even toyed with the idea of running as an independent candidate five years ago. But he always baulked, not sure he could make a successful adjustment to a parliamentary career, and accepts that door has closed.

“There were junctures where I should have jumped at the opportunity,” he reflects.

“I wonder whether I would have been better served with a cooler temperament. I’m a good persuader and a good relationship guy, but I’ve got a visceral temper and I can be a bit harsh with people.”

Being an outsider has also fuelled Pearson’s often blunt-edged approach. His intensity can be effective, but also jarring. He has had a seat at the negotiating table while throwing truth-bombs from outside the room. He has been unremitting in his mission to provide social and economic justice for his people.

“When push comes to shove with a minister, I’ve got to charm them or I’ve got to cajole them or I’ve got to fight them,” he acknowledges.

“But you’ll never change things very much if you are relying on that as the means to get the government to do the right thing … you need a system that has been designed to do the right thing all the time.” Again, it comes back to the Voice.

In order to “survive” in the square of public debate, Pearson developed a “hardheaded mindset” so nothing fazed him. He is capable of critical self-reflection and re-examination of his ideas but admits some of the attacks have hurt, including a campaign by Nine newspapers to undermine the GGSA programs. It was reported that the organisation suffered from staff bullying by management and an exodus of employees, and the education outcomes achieved were questioned.

“That’s the real hard shit,” Pearson concedes.

“The usual method I’ve had didn’t quite work for me, because I started to feel a bit frail when the work I had done was being attacked and kids were going to suffer as a result.”

GSSA has federal funding for a pilot program until September 2025.

Pearson has five brothers and one sister. Last year, his sister died.

“It was devastating to lose our baby sister,” he says.

“And life ever since then has had no taste. I have children, and I love them very much, but I’ve never encountered a loss like my sister.”

Pearson became trustee of her estate and discovered two bank accounts, one with 33 cents and another with 67 cents, as “the sum total of her earthly wealth”. She wanted a job but could not find one.

“I should have fought for a jobs program because nobody else in that Hope Vale cemetery where we buried her would have been in a different position,” he says.

“I gave her money every other fortnight, but I could have done more.”

He adds: “Getting a wage rather than a welfare cheque is the only thing that I can see that is going to repair the fabric of these remote communities.”

There is a melancholy about Pearson. Death stalks him. He survived cancer a decade ago. He knows time is running out, for himself, and for reconciliation. His life mission, instilled by the Lutherans, is to serve God and his fellow man. Glen Pearson died at age 62. His son is now 57.

“The fact that my father died so young, and I’m five years away from his age is there in the back of my mind,” he says. With a long sigh, he ruminates on what failure to carry the referendum will mean.

“We need Australians to genuinely believe and understand that this referendum is the most important thing we can do to secure reconciliation. There is no Plan B. If the country cannot recognise Indigenous people, then the country is basically saying we are not interested in reconciliation. I think the reconciliation agenda will die, and it should die.”

The voice to parliament and government, Pearson argues, is an act of faith and love. He grew up in a place called Hope Vale, and the virtue of hope, above all else, springs eternal. After a decade of consultation, coalition-building and compromise in the search for a radical centrist approach to recognition and reconciliation, he believes it is time to decide. He reveals that polling and focus group research by C|T Group, formerly Crosby Textor, shows strong support for the Voice, especially from young people, women and migrants. A challenge remains to “convince the old Aussies to let go of their fears”, he says.

He believes the referendum will be supported because it speaks to a yearning deep within the Australian soul.

“I think we are all troubled by the absence of reconciliation,” he says.

“Black fellows and white fellows have been troubled by it. It’s like we haven’t found our heart as a nation. There’s an emptiness there. We know that recognition never happened originally, and it still has not happened.

“A lot of the antipathy towards our people ... is a result of this. Richard Windeyer, in the 19th century, was a vociferous opponent of Aboriginal rights, and yet he said: ‘What means this whispering in the bottom of our hearts?’ And this whispering is still there, right, about things that have not been settled between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. And yet important components have been achieved since the 1967 referendum: land rights, the recognition of our history in schools, the presence of Indigenous symbols in the cultural life of the country.

“Now is the time to pull it together to achieve recognition in the nation’s most supreme legal document, which is the Constitution. So, constitutional recognition answers a spiritual need in the Australian nation.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout