Rival Indigenous voice to parliament models explained

Julian Leeser quit Peter Dutton’s Liberal frontbench over the Indigenous voice, despite his reservations about Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s model. Here we explain the proposals put forward by all three.

A referendum on an Indigenous voice to parliament will be held by the end of this year. So far, three models been put forward in a bid to achieve Constitutional recognition for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. We explain them here:

1. The Albanese model

The Albanese government’s and First Nations referendum working group’s model is the one Australians will most likely be voting on between October and December this year.

There may be some changes following a parliamentary committee process, but at the moment it would:

– Enshrine the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice in the Constitution.

– Give the voice power to make representations to the parliament and executive government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Indigenous Australians.

– Give the parliament power to make laws about how the voice would work – including its composition, functions, powers and procedures.

– Parliament would not be able to limit the broad scope of the voice, as that is also enshrined in the Constitution.

The voice question, announced by the government on March 23 reads:

“A proposed law: to alter the constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. Do you approve this proposed alteration?”

Mr Albanese says the Labor government’s voice model will “strengthen parliament’s understanding not supplant its authority” and improve outcomes for Indigenous peoples. “This is not about symbolism, this is about recognition,” Mr Albanese said. “This is about making a practical difference, which we have a responsibility to do.”

2. The Dutton model

Peter Dutton and the Liberal Party have put forward an alternative proposal, with little meat put on the bones at this stage. It would:

– Recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the Constitution, but not through a voice

– Regional and local voices would instead be legislated by parliament

Under the Dutton model, local and regional voices would have their remit narrowly targeted via legislation to focus solely on practical, community-based measures to improve outcomes for Indigenous Australians rather than giving a national body free rein to make representations on any issue affecting Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders. The local bodies would report federally rather than to state governments, but the model could be adjusted as needed over time by the federal parliament. It would sit outside the Constitution.

The local bodies would report federally rather than to state governments, but the model could be adjusted as needed over time by the federal parliament. It would sit outside the Constitution.

“The Liberal Party model will limit the local and regional bodies to issues specific to improving lives and outcomes locally. It has no business in defence, RBA deliberations, energy and environment policy,” Mr Dutton told The Weekend Australian. “It will be in legislation so it can be improved over time.

3. The Leeser model

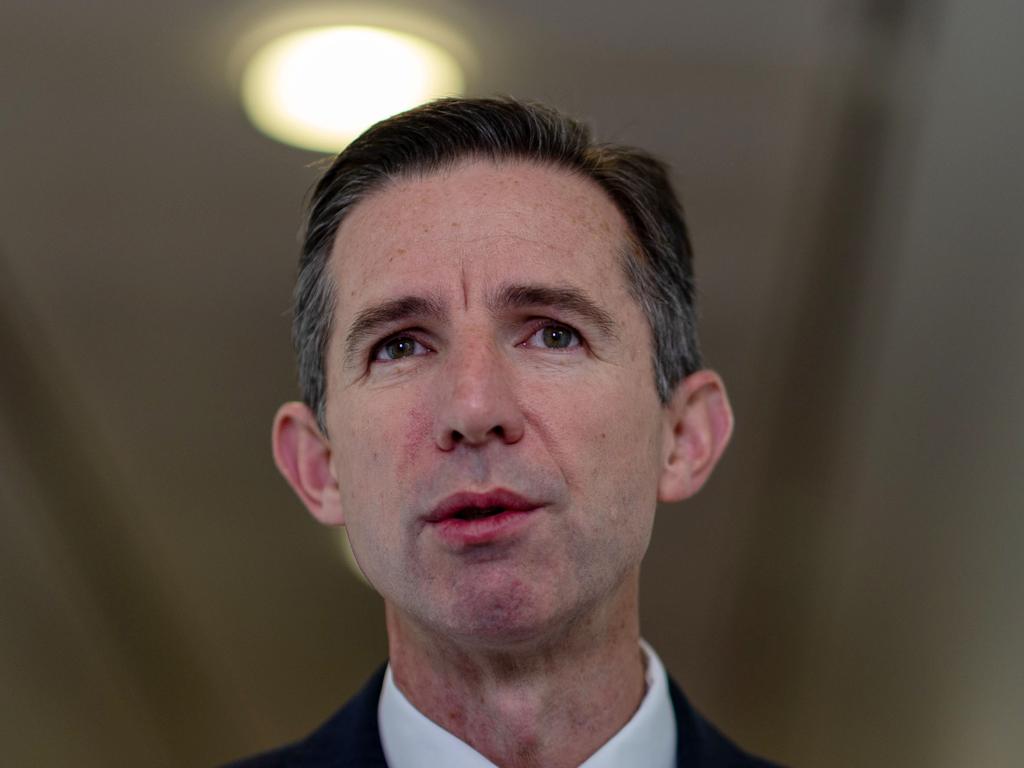

There is a third model the Liberal Party’s highest-profile Yes campaigner, Julian Leeser, is prosecuting. Mr Leeser outlined a blueprint that would let parliament legislate who in the executive government the advisory body could talk to and what it could talk about, in a proposal radically different to that put by Anthony Albanese.

It would:

– Enshrine the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice in the Constitution.

– But remove the second clause of the government’s proposed constitutional amendment, meaning parliament would be given the power to legislate everything about the voice – including its scope.

– Mr Leeser refers to this proposal as the “minimalist constitutional model”, which he says removes the risk of High Court challenges relating to the voice.

Mr Leeser, the Opposition’s shadow Indigenous Affairs spokesman, this week quit the front bench over the Liberal Party’s stance on the voice.

He has been involved in working on the voice for a decade but resigned from shadow cabinet after being able to bring the Liberal Party round to his side.

“I respect the experiences they bring to the parliament, the communities they represent and the like and they have a different history on these issues to the history I have,” Mr Leeser said.

“No-one else in our party room has this experience,” he said. “I think I’m in a unique situation.

“I’ve also tried to keep faith with my Liberal values. My desire to conserve our institutions like the Australian Constitution with my desire to seek better outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.”

Liberal moderate Simon Birmingham has urged Anthony Albanese to embrace Mr Leeser’s model, rejected by shadow cabinet, saying it could be a “game-changer for many Australians”.

But University of NSW constitutional law expert George Williams said Mr Leeser’s proposal “gutted” the government’s model and “left us with a voice that may have no voice”.

STATE-BASED MODEL

South Australia

On March 26, the South Australian parliament to witness the historic passage of the first state-based Indigenous voice to parliament. The First Nations Voice Bill 2023 passed through both the lower and upper house unopposed.

SA’s First Nations Voice will consist of representatives from Local First Nations Voices, and will have the ability to address either house of parliament on any specific Bill that is of concern to South Australia’s First Nations People.

The SA Voice will comprise 42 elected delegates drawn from seven regions who will have a legally-enshrined right to meet with State Cabinet twice a year and have two meetings a year with the chief executive or commissioner of every government department.

It’s adoption followed two rounds of extensive consultation with Aboriginal communities, organisations, and people.

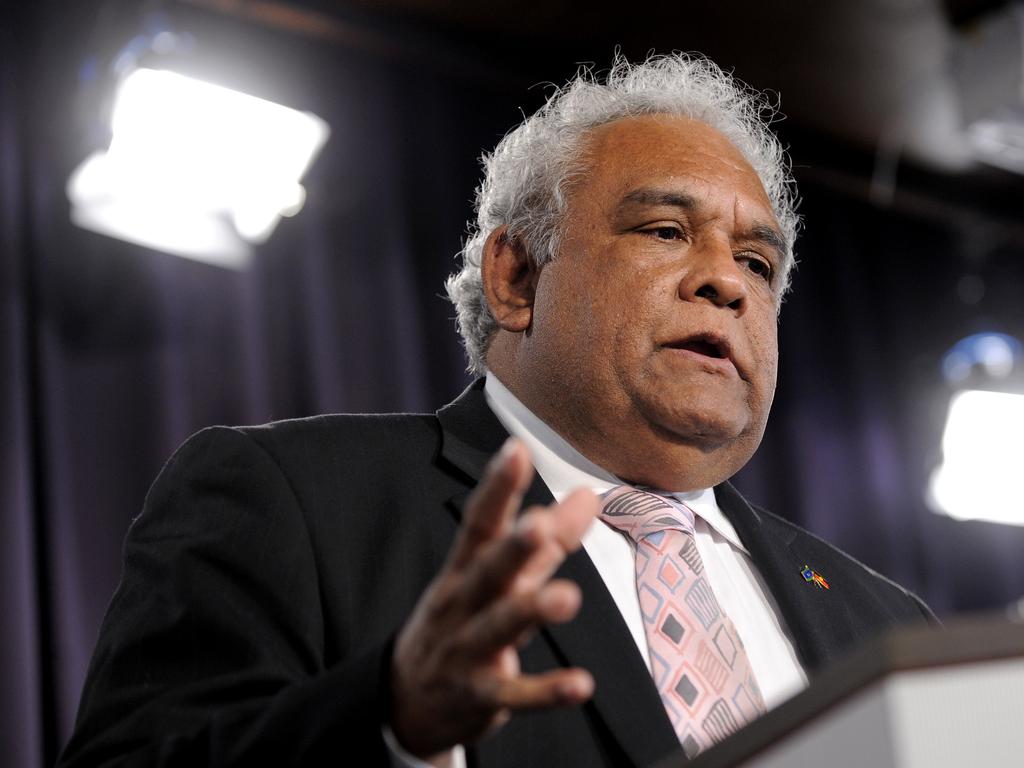

“This is an advisory body,” South Australian Attorney-General Kyam Maher said.

“It will have a right to address parliament on legislation as it goes through as it concerns Aboriginal people. But it won’t have any right to stop, any right to amend, any right to veto. It will simply have the right to have voices heard so that when governments make these decisions they are taking into account the views of Aboriginal people.

“What it doesn’t mean is that there is a new third chamber of parliament that’s going to be able to veto or change what the parliament does. That’s not what it is at all.”

The prospect for legal wrangling with Indigenous groups who feel their advice has been ignored is also reduced by the SA legislation explicitly acknowledging the non-binding nature of the feedback from Voice delegates.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout