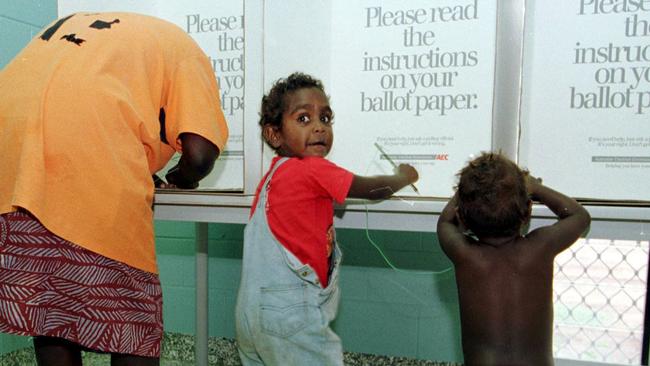

How should I vote in the Indigenous voice referendum?

It’s your vote – but will you choose ‘yes’ or ‘no’? This is a just-the-facts, opinion-free guide to what the Indigenous voice to parliament means. Our goal is to help you cut through the spin to make up your own mind.

On Saturday, October 14, very Australian over 18 will be required to vote either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ in a referendum on establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to parliament.

But many are still undecided and there are both passionate proponents and opponents, all arguing they are right, publishing their thoughts and opinions every day.

It can be confusing, so The Australian is publishing this point-by-point, opinion free guide to what the Indigenous voice to parliament will be, the arguments for and against and the potential consequences and the implications of voting ‘yes’ and ‘no’.

You can also read all our ongoing news and opinion coverage here.

What is the voice?

The Indigenous voice to parliament will be a permanent, independent, representative advisory body for First Nations people to advise the Australian parliament and government on the views of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

When is the vote?

The Senate has passed legislation allowing the referendum to proceed and the vote will be held on Saturday, October 14.

What will the voice advise on?

The Government says it will advise parliament and the executive – that is, Government politicians and bureaucrats – on matters that affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders differently to other Australians. This has been a matter of some controversy, with questions asked about whether it would seek to advise on broad issues like changing the date of Australia Day, or the location of defence bases.

Yes advocates and the Government say the Voice will focus on health, education, employment and housing.

Why do we need a voice?

Advocates including Anthony Albanese say a voice is crucial for improving the lives of Australia’s first people, and would ensure local people are heard before important policy decisions are made.

Indigenous Affairs Minister Linda Burney says the voice will seek to address grinding disadvantage suffered by Indigenous families living in poverty and poor health.

Constitutional expert professor Megan Davis says the voice will create momentum for practical change to help Australia ‘close the gap’ between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Historian professor Marcia Langton says disenfranchised First Nations people in troubled communities such as Alice Springs desperately need to be heard on a national stage.

Cape York Partnership director Noel Pearson says the voice would help address the problem of racism by finally bringing Australians together.

What are the arguments against a voice?

The No campaign says a voice will be risky, divisive, unprecedented and permanent. Their slogan is 'if you don't know, vote no'.

Former Labor president Nyunggai Warren Mundine says while constitutional recognition of First Nations people is a good idea, the voice would be elitist, appointed rather than elected, and that most Indigenous Australians do not understand or want it.

Some opponents, including independent senator Lidia Thorpe, say the voice does not go far enough, preferring a treaty and acknowledgment of First Nations sovereignty, and is a distraction from solutions to practical issues including high rates of child removal, incarceration and deaths in custody.

Federal opposition indigenous affairs spokeswoman Jacinta Nampijinpa Price says billions of dollars have already been wasted on the false premise that Indigenous Australians must be treated differently.

One contentious aspect of the voice design is that it could be justiciable – that is, the voice could go to the courts to demand government act on its advice. Constitutional experts disagree on the significance of justiciability. Anthony Albanese has argued parliament will be supreme over the voice and its advice would not get bogged down in court action.

You can read all our opinion and commentary writers for and against the voice, here.

How did we decide to have a referendum?

In 2010, Prime Minister Julia Gillard established an expert panel to advise on constitutional recognition and in 2015 PM Malcolm Turnbull established a referendum council, which oversaw regional ‘dialogues’ or consultation sessions with First Nations people around the country.

In 2017, the dialogues culminated in a constitutional convention that agreed a form of words for recognition: the Uluru Statement From The Heart, which called for a voice to parliament, a treaty, and a truth-telling process.

In 2022, upon his election, Anthony Albanese declared he would enact the Uluru Statement in full, beginning with a referendum in his first term of government.

What will the question be?

The Referendum Working Group, a council of elders established by the Prime Minister, agreed on a voice question in March 2023.

It reads: “A proposed law: to alter the constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. Do you approve this proposed alteration?”

The referendum will take place between October and December, 2023.

How will it work?

There may be some changes following a parliamentary committee process but at the moment it would:

– Enshrine the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice in the constitution.

– Give the voice power to make representations to the parliament and executive government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Indigenous Australians.

This is likely to be the model upon which we vote at the referendum.

There are three other alternative models for how voices could work, which are ideas proposed by Opposition leader Peter Dutton, leading Liberal Julian Leeser, and the South Australian government, which has already enacted its own Voice.

If Australians vote yes, the following words would be inserted into the Constitution:

In recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia:

There shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice;

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

The parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures.”

How does a referendum get passed?

To pass, a referendum must gain a ‘double majority’: that is, more than 50 per cent of all votes nationally, and more than 50 per cent in at least four of the six states.

All Australians aged over 18 must vote and the result is binding, meaning the Government must enact the result of the referendum.

How do I register to vote?

If you’re enrolled to vote in elections, you’re also enrolled for the referendum. If you need to enrol, or check or update your enrolment, the Australian Electoral Commission can help.

What happens if we vote yes?

If Australians vote ‘yes’, the constitution will be amended and federal parliament will meet to pass legislation creating the voice.

This debate will include practical measures, such as how members of the voice are elected or appointed, where they will meet and how often, and what they will be able to advise upon, and how that advice will be given.

The legislation will also set out limits to the voice’s power, including to what extent the voice’s advice must be accepted by the parliament and government — and what happens if the government or parliament rejects the voice’s advice.

What happens if we vote no?

Nothing. The constitution will remain unchanged and the voice will not be established.

What is the history of this idea?

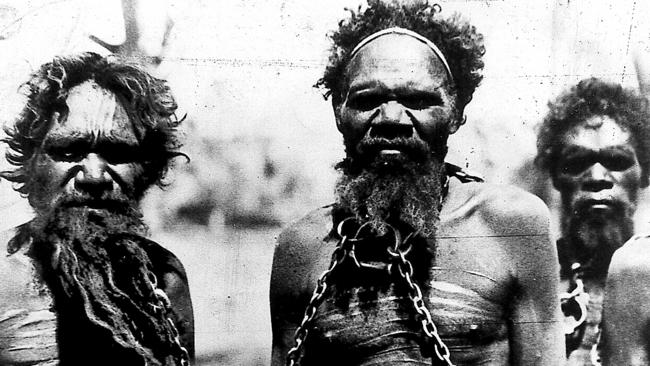

From the first moments of contact between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians and European colonisers, Australia’s story has been contested.

As European diseases such as smallpox devastated coastal populations, the clearing and settlement of land for agriculture led to violent frontier conflict, including massacres, as First Nations communities and white colonialists attempted to eke out a living.

Calls for constitutional recognition of Aboriginal people date all the way back to Federation in 1901, but over the 20th century other causes have often overshadowed this debate.

From the 1960s, land rights became a rallying cry for many First Nations communities, as mining companies won leases for mineral exploration in traditional homelands and Aboriginal communities objected to being excluded from the commercial development of their land.

In 1967, Australians voted overwhelmingly in a referendum to grant the Commonwealth power to legislate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, also ensuring they would be counted in the national census for the first time.

In 1992, the High Court recognised native title for the first time in the Mabo decision, followed by the Keating Government’s Native Title Act.

From the 1990s, calls for an apology to the Stolen Generations of Aboriginal children, who were taken from their families throughout the 20th century, grew louder, culminating in the walk for National Reconciliation across the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 2000.

In 2007, then Prime Minister John Howard proposed a new preamble to the constitution which recognised the First Australians, but he lost the election to Kevin Rudd, whose promise to apologise to the Stolen Generations captured the public mood.

In 2008, Prime Minister Rudd issued the apology amid emotional scenes in federal parliament, declaring: “For the pain, suffering and hurt of these Stolen Generations, their descendants and for their families left behind, we say sorry.

“And for the indignity and degradation thus inflicted on a proud people and a proud culture, we say sorry.”

In 2022, the ongoing blight of deaths in custody saw protesters join Black Lives Matter marches in Australia’s major cities.

Has this ever been tried before?

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have never been expressly recognised in the Constitution, but there have been several national representative bodies, all of which have been abolished.

Supporters of the voice say because it would be embedded in the constitution, it could not be abolished as the previous bodies have been.

The first attempt was the National Aboriginal Conference, an advisory body created in 1973 by the Labor government of Gough Whitlam, which advocated for the development of a treaty.

It was abolished in 1985.

Next came the Aboriginal Development Commission, created by Malcolm Fraser, and in 1990 Bob Hawke’s government established ATSIC – the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission – which was a national body made up of 35 regional councils, elected by Indigenous Australians.

Its first chair was Dr Lowitja O’Donoghue, a highly respected Yankunytjatjara woman and former nurse who played a crucial role in the negotiations over native title legislation.

ATSIC’s role was to advise federal, state, territory and local governments, advocate for Indigenous people and to deliver and monitor programs for First Nations communities.

ATSIC was abolished by John Howard’s government in 2004 amid a series of integrity scandals.

It was replaced by the National Indigenous Council, an appointed advisory body which included footballer Adam Goodes and politician Warren Mundine, which lasted only three years.

The next attempt was a National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples, which was a parliament-like body of appointed and elected delegates who made submissions to Government and parliament and advocated on behalf of First Nations people.

In 2013 the government of Tony Abbott withdrew the Congress’ funding and it folded in 2019.

Further information

We are covering developments on the voice in our daily news podcast The Front, which is available for free, wherever you get your podcasts and in The Australian’s app.

Find The Front in Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

Subscribe to The Australian

You can get all The Australian’s journalism every day by subscribing here.

Download our app in Apple’s App Store or Google Play

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout