Anthony Albanese PM in all-or-nothing brawl over Indigenous voice to parliament

Anthony Albanese has set up a three-month brawl with Peter Dutton after endorsing a constitutionally enshrined voice, which boasts powers across all arms of the government.

Anthony Albanese has set up a three-month political brawl with Peter Dutton after endorsing a constitutionally enshrined Indigenous voice to parliament, which boasts powers across all arms of the government to intervene “early in the development of laws and policies”.

The Prime Minister rubber-stamped the 23-person referendum working group’s eight design principles and its proposed new chapter to the Constitution, which recognise and establish an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice to parliament.

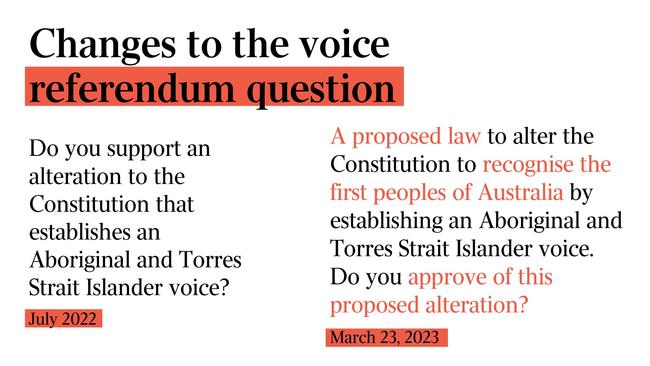

The final referendum model approved by federal cabinet on Thursday featured minimal changes to the constitutional amendments flagged by Mr Albanese at the Garma festival in July last year, despite concerns raised by Solicitor-General Stephen Donaghue about legal challenges.

The Australian understands that allowing a voice advisory body to “make representations to the parliament and the executive government on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples” has firmed Mr Dutton’s opposition to the referendum.

The decision to retain “executive government” in the referendum question sparked concerns from the Coalition and constitutional experts that the purpose of the voice was too vague and could lead to perverse outcomes.

These include whether the voice body, whose members will be selected by local Indigenous communities and not the government, will be able to directly engage with the public service and make representations on policy and laws across all departments and agencies, and whether they will be bound by cabinet confidentiality.

The insertion of the word “commonwealth” executive government also leaves open the likelihood of state and territory governments pursuing their own versions of the voice and treaties.

Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus – who attempted to insert additional words to the voice to protect against legal challenges – secured a minor amendment giving parliament powers to “make laws with respect to matters relating to the … voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures”.

Flanked by referendum working group members, Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney and Mr Dreyfus, Mr Albanese fought back tears as he declared “we’re all in” on Australia’s first referendum since 1999.

Labor’s proposal to insert a new chapter in the Constitution – alongside its current sections on the parliament, the executive, and the states – marks a dramatic step-up since the failed 1999 referendum attempt to insert a preamble recognising Indigenous Australians.

With senior Labor figures suggesting Mr Albanese is staking his authority on the success of the referendum, which is expected between October and December, the Prime Minister said his push for the voice was “not about symbolism”.

“This is a modest request. I say to Australia, don’t miss it. This is a real opportunity to take up the generous invitation of the Uluru Statement from the Heart. This is about the heart, but it’s also about the head. If you think things have been working up to now, look at the closing the gap issue,” he said.

“This is not about symbolism. This is about recognition, something that’s far more important, but it’s also about making a practical difference which we have a responsibility to do.” A delegation consisting of only six of the 23-person referendum working group – Tony McAvoy, Megan Davis, Thomas Mayo, Ken Wyatt, Marcia Langton and Pat Anderson – led negotiations with the government on the referendum wording and secured a deal with Mr Albanese on Wednesday.

Sources close to the negotiations said the delegation, which reports back to the wider working group, had rejected changes suggested by Mr Dreyfus because they weren’t “necessary”.

The Australian understands while Mr Dreyfus’s suggestion to include specific wording to prevent legal challenges was rejected, the group returned with their own tweaks to the amendment that bolstered parliament’s power over the voice. The wording is now broad enough that the parliament could make any manner of changes to the body, including tweaking the voice should threats of legal challenges emerge.

Constitutional law expert George Williams, a member of the government’s constitutional working group which last met on February 2, described the change as expanding parliament’s power over the voice and designed to hose-down concerns from the conservative side of politics.

Mr Albanese said the government would establish a joint parliamentary committee to consider legislation on the constitutional wording, which will be tabled next Thursday. A parliamentary vote on the referendum question will happen in June, setting-up a showdown between Mr Albanese and Mr Dutton.

The Prime Minister pledged to fight any attempts to change the government’s proposed changes to the constitution: “are there any circumstances in which this will not be put to a vote? The answer to that is no. Because to not put this to a vote, to not put this to a vote, is to concede defeat”.

“You only win when you run on the field and engage. And let me tell you, my government is engaged. We’re all in,” he said.

“Of course, it (the wording) can be altered, people can have the numbers to alter it. I’ve said though, very clearly and unequivocally that this is the government’s position.”

With the Nationals already opposed to the voice, Mr Dutton warned about legal interpretations of the proposed constitutional changes. “The government can’t out-legislate the constitution, that’s the reality so if you’re putting forward a form of words which is open to a broad interpretation by the High Court then the parliament can’t rectify that. That’s the issue here,” he said.

“What the government’s proposing at the moment is that the Australian public will go to vote on a Saturday and then from Monday on for six months there will be consultation on the model. Now that is putting the cart behind the horse.”

Mr Dutton said Mr Albanese must release the Solicitor-General’s advice on the inclusion of “executive government”.

“The Prime Minister owes it to the Australian people to release that advice and there’s precedent for it and it would be very strange … for them not to release that,” he said. Despite releasing Solicitor-General’s advice when the Scott Morrison multiple ministries scandal erupted, Mr Dreyfus said such a release was “inconsistent with the practice of successive governments over many years”.

“This has been a comprehensive and rigorous process. Some of the best legal minds in this country have been working on this. The Australian people can be confident that we’ve got this right.”

Mr McAvoy, Australia’s first Indigenous silk and the working group’s legal expert, said they had “good discussions” with Dr Donaghue and Mr Dreyfus about the need for additional words in the amendment that went specifically to limiting the “legal effect” of the group if need be.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout