PM’s passion lights path towards true change

While I was at the 2008 apology and walked across the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 2000, it was clear these moments were about resolving a historical stain on our national journey.

The emotion at Thursday’s press conference is understandable; many have devoted entire lives to arrive at this point – that is, a federal government supportive of the concept of Aboriginal agency and willing to spend political capital to change how we do Aboriginal affairs in Australia.

The future awaits, but the Aboriginal leaders surrounding Anthony Albanese on Thursday know that the hand extended by Aboriginal Australia at Uluru is still yet to be grasped. That is the final act, the question Australians are still to answer.

The referendum working group has developed the question, simple and clear, and the design principles provide some meat to the constitutional bones about what the voice itself will be.

The Aboriginal hand has been extended. Recognition has two dimensions. First, it is a recognition of humanity’s deep historical connection to the Australian continent and surrounding islands. Australia cannot deny our history because its legacy is a reality we cannot escape.

Second, recognition in itself is a fundamental basis for reconciliation, but in practical terms the voice as a representative body of First Peoples can provide the developmental framework to overcome the legacies of colonialism that continue to torment and diminish so many Aboriginal people. The primary KPI in which we see this legacy is in the policy outcomes broadly categorised as Closing the Gap.

And while historical recognition is important, the simple reality is that the voice will change how we do Aboriginal affairs. It will have, without a doubt, the outcome of better policy, better use of taxpayers’ money and better results. It is important to think about the relationship between the voice and the country’s state and territory governments. To be frank, the federal government has little direct role in the delivery of programs to Aboriginal people.

The federal government is, undoubtedly, a large funder of programs that service Aboriginal people, but it is the state governments that have a direct relationship with Australia’s Aboriginal citizens. This is why, across the course of the past decade, all state governments have moved to implement some form of a voice. Why? The reason has been because everyone – including ministers, Aboriginal people and taxpayers – has become frustrated with the lack of outcomes. If you accept that Aboriginal policy is characterised by failure, you must accept that the way we develop and implement policy needs a fundamental change.

State governments have had great difficulty in developing and implementing successful policy that seeks to address the large gaps in Aboriginal outcomes because of the lack of appropriate, expert and experienced Aboriginal perspectives. Governments have struggled, across decades, to understand the Aboriginal context; that is, who should they speak to? Who can provide a view that has authority and respect?

Western Australia’s “voice”, the Aboriginal Advisory Council, embedded in legislation since 1972, has risen and fallen on the interests of the minister of the day. It has always lacked the authority to be the Aboriginal voice because of the way the members of the council are chosen.

The high-water mark for the council came with the election of the Gallop government in 2001. The Gallop government entered into an accord with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission to draw on the credibility of the representative model that underpinned ATSIC. It provided an avenue of advice to the Gallop government. This was a successful model that floundered when ATSIC was abolished.

The existence of the WA Aboriginal Advisory Council has never been the source of litigation as its role is specifically designed to advise the government. As minister, I relied on the advice of the council on all matters that affected Aboriginal affairs.

The success of policy was because of Aboriginal expertise and input. No government could have had policy success without deep Aboriginal engagement.

A successful referendum also has within it an embedded assumption around Aboriginal agency; that is, Aboriginal people have the expertise and experience to make decisions for themselves.

This is the source of the Prime Minister’s emotion. For too long government has assumed a deep and entrenched Aboriginal incapacity. We have, as the Prime Minister said, a historic opportunity to change this country and embrace within our nation’s constitutional fabric the oldest continuing culture on earth. The voice is a constitutional recognition that the government is not the repository of all expertise. This is why, at its heart, it is a conservative concept.

A potentially major benefit the voice may bring is dealing with the current dysfunction between the states and federal government in Aboriginal policy. Currently, each state and territory has its own consultative approach. The voice has the potential to integrate a national representative structure with state and territory arrangements and develop a cohesive national approach to policymaking – improving the current segmented and poorly co-ordinated policies between the federal government and the states and territories.

The voice may well prompt a broader alignment of policymaking, particularly in regional Australia, where state and federal priorities often compete.

With his tears, the Prime Minister has welded the aspirations of Aboriginal Australia to the simple question for Australians to answer.

All evidence points to the reality that Aboriginal people actually do know what they are talking about when it comes to themselves.

We can, as a nation, bend the future beyond the course set by history – the inevitability of continued failure – or take a very small chance by amending our Constitution to ensure governments simply take advice.

The risk is small, the prospect of change enormous. The answer is obvious.

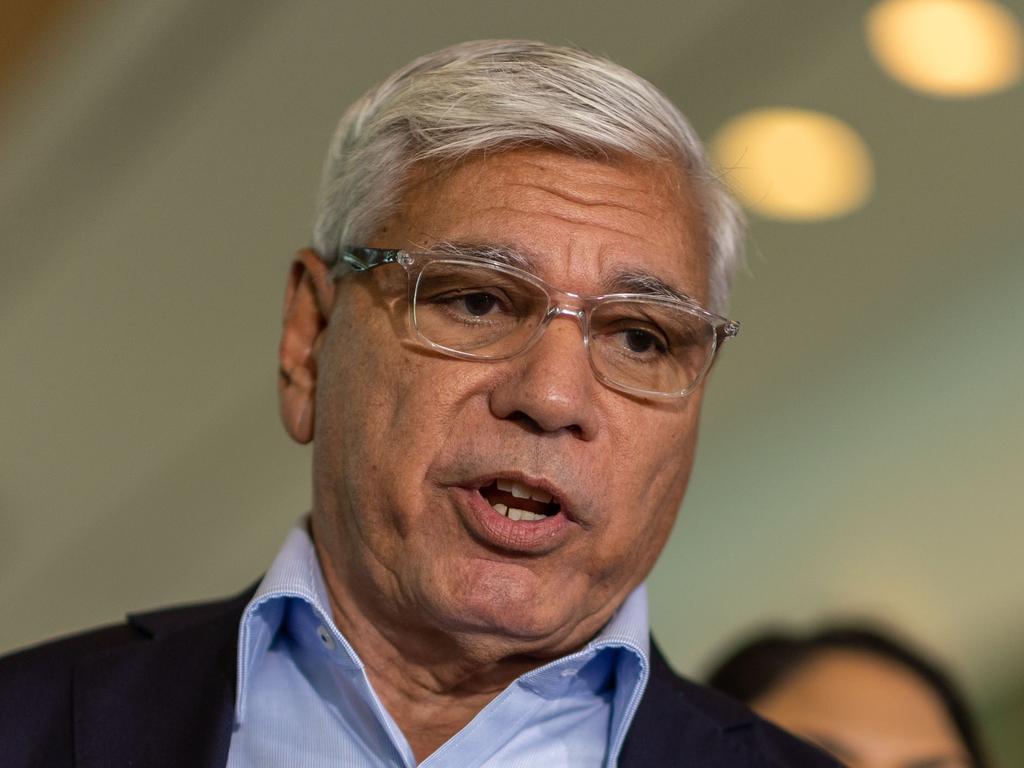

Ben Wyatt is a former treasurer and Aboriginal affairs minister in Western Australia.

Very occasionally in politics you get a sense that a decision has been made that will change the trajectory of our future. In Aboriginal affairs, these experiences are few and parlous.