Warren Mundine mocks Anthony Albanese’s ‘crocodile tears’ on Indigenous voice

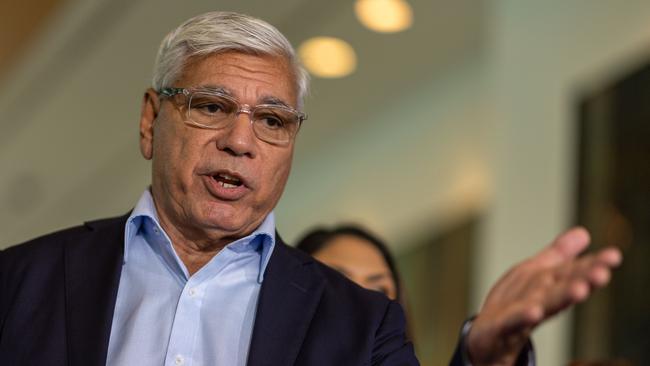

No campaign leader Warren Mundine has accused Anthony Albanese of ‘crocodile tears’ over the voice after the PM refused to meet an Indigenous delegation on Wednesday.

No campaign leader Warren Mundine has accused Anthony Albanese of “crocodile tears” over the voice after the Prime Minister refused to meet an Indigenous delegation on the eve of Thursday’s announcement.

Mr Mundine, one of the most prominent Indigenous voices opposed to the constitutional reform, told The Australian on Thursday that Mr Albanese had the opportunity to meet 20 Aboriginal people from around the country on Wednesday and had knocked them back. The delegation had travelled to Canberra to express their concerns about the voice, but could secure meetings only with the Coalition and some members of the crossbench.

Mr Albanese choked back tears on Thursday as he announced the wording of the question to be put to Australians at a referendum later this year.

Mr Mundine said his emotion sat in contrast to his unwillingness to meet Wednesday’s delegation.

“If he‘s fair dinkum and those tears aren’t crocodile tears, he should have met with them and listened to their concerns,” Mr Mundine said. “They are the sort of people he says the voice should be working for. He had the chance to prove that, and he didn’t.”

While Mr Mundine acknowledged there was still room for improvement in the lives of Indigenous Australians, he said there had been significant gains in recent decades without a voice. Discriminatory laws had been abolished, the number of Aboriginal businesses had climbed, and there were growing numbers of Indigenous doctors, lawyers and professors, he said.

Mr Mundine said he believed the push was being driven by prominent Indigenous figures looking to entrench their influence. “This to me is just a power struggle from people who feel they’re going to be left behind,” he said. “They‘re all lawyers and academics or public servants, they’ve been living off the teat of government, and that’s what this is all about. This is the battle for keeping them in power.”

Mr Mundine is part of a group of Indigenous leaders including Nationals senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price campaigning against the voice. Independent senator Lidia Thorpe and Tasmanian Aboriginal leader Michael Mansell have also expressed opposition to the voice on the grounds it should be preceded by a treaty.

Other senior Indigenous figures around the country, meanwhile, welcomed the latest progress. Uluru Dialogue senior member and constitutional lawyer Eddie Synot said arguments from opponents that the voice would divide Australia on race were “disingenuous and unfortunate”.

“Really we should be embracing what is an amazing opportunity before us to finally recognise and provide representation to Indigenous peoples and at the same time actually do something substantive and practical about changing … people’s lives,” he said. “We’re talking about some of the most impoverished and vulnerable people in this country, and yet some people are quibbling over the most spurious claims about race. It’s ridiculous.”

A successful referendum would not only help improve the lives of disadvantaged Indigenous people, it would also be a powerful symbolic gesture.

“I believe it will have an immeasurable difference into the future about some of the very simple things like how the decisions are made, but also our sense of self, who we are and how we participate in society, and the relationships we have,” Mr Synot said.

In Western Australia’s remote Kimberley region, Bunuba man Patrick Green gathered around a television in Fitzroy Crossing with other elders to watch Mr Albanese’s address live. “At least somebody‘s got the balls to have a go at finally taking the next step to try and seal it into the Australian Constitution,” he said.

“Hopefully, it’ll be supported again like the ’67 referendum by a large number of people in Australia recognising the first people of this country.”

Indigenous people in Australia, he said, had long felt like second-class citizens. An enshrined voice could finally help address issues affecting Indigenous communities. “Hopefully we can address a lot more of our concerns that … continually keep us down.”