Indigenous voice to parliament naysayers speak for small minority of our people, writes Pat Anderson

All Australians should learn more and question the claims of those with power who say No to an Indigenous voice to parliament. When you dig a little deeper, you’ll find they only speak for only 10 per cent of our people.

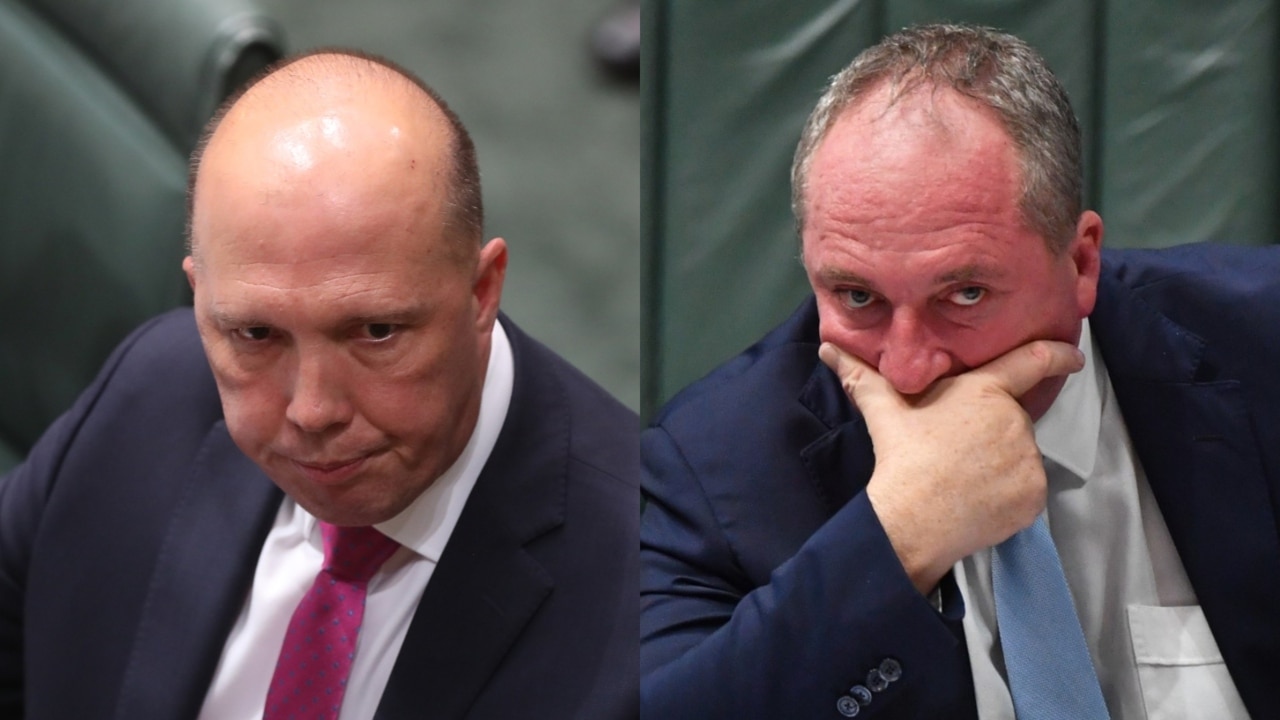

This week there were some prominent No case figures who sought to undermine the voice proposal.

They were not at the First Nations regional dialogues and they did not hear the frustration and the overwhelming sense of powerlessness expressed by the dialogue delegates about their inability to contribute to the swirling incoherency of policies directed at their communities.

Those naysayers were not at the dialogues for a reason. They have a voice.

The exhaustive and deliberative process of the regional dialogues – unprecedented in our nation’s history – was designed to hear from people who don’t already have a voice. Yes, it is true some leaders in the struggle and some prominent figures attended but the majority of participants were those who don’t get to have a say.

They don’t have fancy access passes to Parliament House so they can’t run down to Canberra lobbying politicians. They aren’t people who have the ear of the prime minister of the day. They don’t effortlessly get meetings with the secretaries of departments or are on first-names basis with the agency that runs Indigenous Affairs. They don’t appear on The Drum, Q&A, Radio National, Sky News, the national news or get their opinion published in a national newspaper.

Yet we will get to hear from these people if the voice becomes a reality.

For those who are not familiar with the Uluru Dialogues and the process that led to the Uluru Statement from the Heart, let me recap.

In December 2015, prime minister Malcolm Turnbull formed a Referendum Council tasked with the job of consulting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples on what constitutional recognition meant to them.

This was a retrofitted consultation process because communities hadn’t been consulted adequately in 2011. By 2015, symbolism was the politicians’ model because tokenism was all both parties could agree on.

The government didn’t hand the dialogues to mob on a platter. We had to fight for the meeting where Tony Abbott committed to a new dialogue and we had to fight to persuade the political elites, especially the department, that a dialogue process was needed.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander members of the Referendum Council designed a structured deliberative dialogue process. We wanted to avoid the “tick box” consultation that we see too often in our communities and instead follow best practice engagement to ensure all participants were well informed, understood all the options available and had an opportunity to really dig in deep.

In 2016, the prime minister and the leader of the opposition endorsed the plan to conduct the series of regional dialogues culminating in a national constitutional convention at Uluru. They also signed off on the multiple concepts of recognition. From 2011 to 2017 anyone paying attention knew that “recognition” did not mean it’s dictionary meaning “acknowledgment” or symbolism.

The expert panel report in 2012 and Anne Twomey’s excellent advice saw the nation move on from a stand-alone preamble or statement of recognition as being an acceptable form of recognition.

The regional dialogues engaged 1200 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander delegates with representatives from First Nations traditional owner groups, First Nations community organisations and First Nations individuals.

There is deliberate misinformation that the dialogues were only 60 per cent Indigenous. This is false.

Each regional dialogue then elected members to represent them at the national convention at Uluru. And the Uluru Statement from the Heart, which called for a constitutional voice, was the consensus position through this long and deliberative process with our people.

I was the co-chair of the Referendum Council. I was physically at every regional dialogue and at the national convention at Uluru.

This was the most difficult work of my life.

At times the conversation was hard. Sometimes heated. Many of the stories shared were heart-breaking. We cried. We yelled. We laughed. We didn’t all agree all the time. But that was the point; we don’t all agree and so the records of meetings for each dialogue captured the raw butcher’s paper and the length and breadth of our people’s ideas and views. Extreme and conservative. Politically palatable and utopian ideas. We did this because we wanted to garner the trust of our people – that we would faithfully capture their views and record them.

In some cases the conversations were slow because multiple interpreters were used to ensure people for whom Indigenous language was their first, second and third language were included.

At the Ross River dialogue we flew in early to run the entire process by the Alice Springs Interpreter Service because four interpreters were required.

The culmination of all that butcher’s paper and whiteboard work was that we all agreed that the status quo could not continue. We agreed that we should take the opportunity of changing the “big law” of Australia to provide a circuit breaker and provide an opportunity to be heard. That having a say in the laws and policies that impact us would improve the shocking situation we see in our communities day in and day out – in health, education, housing – in every area.

Our people issued the Uluru statement to the Australian people because we thought it was too important for it to get caught up in the abysmal politics we are sadly witnessing right now.

Our old people predicted this in 2017 at the Rock, that politicians couldn’t help themselves but make our issues a political football.

We collectively believed in the Australian people’s ability to see past the politics and walk with us for a brighter future together.

That was almost six years ago. We have since lost some of the old people who attended.

Warren Mundine wasn’t at the dialogues. Jacinta Price wasn’t at the dialogues. Kerrynne Liddle wasn’t at the dialogues. Lidia Thorpe attended and walked out of the conversation at Uluru, as is her right, but the rest of the group reached a consensus position and added their signatures to the Uluru statement.

All these people have a platform which they can and do use to question the process and throw shade on the outcome. All but Mundine is a professional politician. They are a Canberra voice.

But they can’t change the facts. Those of us who were there know how robust the process was to reach consensus.

And the fact that polling earlier this year shows that 80 per cent of our people support the voice (with 10 per cent undecided) is testament to the validity of the process. This polling is backed up by the Reconciliation Australia barometer that found 88 per cent of our people support the voice.

I encourage all Australians, you, to learn more and question the claims of those who already have a voice. When you dig a little deeper you’ll find they speak for only 10 per cent of our people. Which is exactly why a formal First Nations voice, enshrined in the Constitution, which has the ability to hear directly from community on the ground, is so badly needed.

Pat Anderson is an Alyawarre woman and was co-chair of the Referendum Council that ran the Constitutional Dialogues.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout