Anthony Albanese did not appreciate the Indigenous voice to parliament challenge

This is despite some polls showing support for the voice wallowing in the mid-30s, 20 per cent behind the No case, and still falling. Even the most favourable polls place the voice at least 6 per cent behind.

Privately, leaders of the Yes campaign are tense, though still genuinely hopeful that a beneficent Australian spirit will deliver a close victory. The No camp is very confident, worried only that some late campaign catastrophe may befall them.

The predictive challenge is the lack of reliable precedents. Referendums are not elections, with micro-sampling and localised campaign pitches, so political polls are no help. Every referendum is on a different topic, so guidance is limited. One past referendum result that may worry the No camp and uplift the Yes is the 1951 Communist Party referendum, effectively about whether the government should have the power to ban political parties deemed dangerous to the nation.

Like the voice, this was a referendum about the societal depth of Australian character. A No vote actually was a Yes vote for uncomfortable political freedom, even at the height of the Cold War. Australians magnificently voted against political outlawry by a tiny national majority and with the states split three-three.

There will be plenty of time after the result to dissect the tactics of both sides, catalogue disasters and triumphs, and above all to pin blame on chosen scapegoats.

But right now, without the coloured lights and theme music of a referendum premiership, is the time to think seriously about the long-term implications of this very bitter contest. Some concern the referendum process itself, but others are much more extensive.

The first and obvious point is about referendums themselves. They are indeed very hard to win, something Anthony Albanese did not appreciate sufficiently at the outset. He had some excuse. The prominent Indigenous leaders advising the Prime Minister along with his chosen legal coterie were saying he would get 70 per cent of the vote. Confidence was in plague proportions. But the Prime Minister’s covert drafting process, refusal to provide even basic architecture and reliance on platitudes rather than argument all have hobbled the Yes side.

Yet these errors were dwarfed by the basic psychology of referendums. The real challenge in a referendum has always been the constitutional temper of the Australian people. They are logical constitutional conservatives. They understand they have a very good Constitution, as evidenced by the lack of military coups, judicial corruption and arbitrary executions. Sitting on this strong constitutional hand of cards, they are reluctant to take any risks.

This means every referendum must prove itself not on balance but beyond all reasonable doubt. This high bar always has been the challenge for any Yes case but particularly on a contentious topic such as Indigenous relations.

This is where the slogan “If you don’t know, vote No” comes in. It certainly has been used cynically as an all-purpose excuse by the No case. But the vilification of its adherents as constitutional cretins has been problematic.

The challenge is that the “Don’t Know” position covers not only the deliberate constitutional ignoramus but also the thoughtfully unconvinced. They must be mightily unimpressed by condescension from Yes voters who may be no more intellectual than some adolescent “On a guess, vote Yes”.

An exhausting, narrow win in this referendum, let alone a catastrophic loss, will have profound implications for any possible future proposal on literally any topic.

After what the Albanese government has gone through, few others would sign up to a withering constitutional poll. Even dedicated republicans must realise any referendum on that contentious topic would be inconceivable in anything but the distant future.

It also is highly dubious that a referendum on the broad subject of Indigenous recognition would have romped home, as many on the No side have claimed. Those same critics would have found objections to placing recognition anywhere in the Constitution – presumably the preamble – and done their best to spook the electorate.

Just as the past six months show how hard it is to win a referendum, they amply demonstrate how easy it is to beat one. Generally, the No case has followed the standard playbook of trying to promote enough doubt, confusion, irritation and mayhem that people are just plain scared to vote Yes.

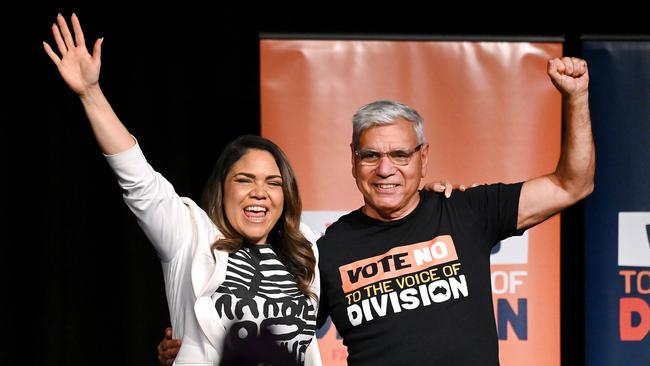

No argument is too silly or cynical. From alleged breaches of international law to Alan Joyce lurking in the background, the No side has not been squeamish. Even Nyunggai Warren Mundine’s own muddling over multiple treaties and voices probably only convinced more Australians that the whole thing was a mess.

There admittedly are two stark exceptions to this rule of confusing one’s way to victory.

Love or loathe her, senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price has been an Exocet for the No campaign. Clear, pungent and plausible, she has savaged the Yes case.

The second exception to the standard play of doubt is that the No campaign has indeed advanced one stark, concrete, national constitutional proposition. This is the vision of an Australian nation absolutely undivided by any question of race or equivalent characteristics. If accepted, this will have profound implications in law, education and politics. Ironically, it is itself a deeply divisive constitutional position.

Well beyond the holding of referendums generally, this poll has widely ventilated the pungent concept of racism. This was inevitable. Yes adherents – particularly desperately anxious Indigenous people – were always going to accuse an outraged No side of being racists. This happened early, but increased rapidly as polls worsened for referendum proponents.

Prominent Yes campaigners tried to argue that accusing the No case itself, its chief protagonists and its arguments of being racist was not the same as calling ordinary No voters racists. They were unconvincing.

Presumably someone who buys a racist argument peddled by racists is indeed a racist.

Much of this argument over racism was misconceived. It is not racist – though it may be desperately mistaken – to disagree with the concept, drafting or operation of the voice. It is the same with the constant accusations of misrepresentation. Many on the Yes side clearly believed any disagreement amounted to outright untruth.

But if not racism, is there some deep, automatic suspicion by many Australians towards any special measures for Indigenous people, particularly (but not only) if they are put in the Constitution?

The referendum outcome will tell much, but many Australians do seem influenced by some pretty confronting positions. They are concerned by “fake Aborigines” getting benefits. They are instinctively sceptical of the financial probity of any Indigenous organisation. They even wonder about the extent to which the appalling plight of Indigenous people is self-inflicted. Problematically, whenever some Indigenous expert condescends to them on the ABC, an Aboriginal corporation is accused of misappropriation or horrific statistics on Indigenous domestic violence are released, they pause for thought.

Much of this has been fanned by the Yes case, with opportunistic attacks on alleged radicals within the Yes machine, association of the voice with plutocratic hate figures (such as Joyce) and a timely interest in Indigenous public finances.

Beyond these inevitable but challenging contests, there circle small groups of genuine ideological opponents, typically on the edges of media or academe.

Some simply are convinced libertarians, arguing from a position that might be unconvincing to most but has a long, principled, theoretical tradition. Others are much more troubling. They have a palpable disdain for Indigenous people as grasping special pleaders who are lazy, greedy and over-privileged. The place of Indigenous people in our history is disputed, as is their relevance to modern Australian society.

To these bitter, adamant enemies, Indigenous people are the race-bludgers of modern Australia. They hold a barely disguised contempt for the Indigenous inhabitants of Australia, their character, capacity, society and history. If these extremists are not racists, they are still something very, very nasty.

Of course, the overwhelming majority of ordinary Australians, as with the overwhelming majority of those who will vote No – including its campaign leaders – have no such conceptions. But citizens of fair and reasoned critique need to be cautious of the source and implications of some more virulent arguments circulating in this referendum.

A plain feature of the referendum is that it exactly follows the social fault-lines evidenced in the 1999 republican poll. The better educated and wealthier you are, the more likely you will vote Yes, especially if you live in an eastern capital. If you are working class with a limited education, a low bank balance and a rural postcode, you probably will vote No.

A huge problem is that if you are a lawyer from Mosman with a higher degree, you tend to congratulate yourself on this evidence of superior intellect. But it really reflects fundamental constitutional problems. First, “elites” have little idea what “ordinary” Australians think. Second, to the extent they do know, they despise them. Third, there are a lot more ordinary Australians than bunyip intellectuals, and everyone has the same vote in a referendum.

The usual condescending response is that the plebs need to be “educated”, as in re-educated, so they agree with us. Of course, what actually is required is a decent civics education program, but that might turn up as many surprises for Mosman as Maroubra. Few superior Australians actually know anything about the Constitution, let alone have read it.

The final great implication of the voice referendum is for Australian conservatism, particularly if the referendum fails badly.

For a variety of reasons, conservatives have battened on to opposition to the voice as their leitmotiv.

Instead of worrying about living standards, education and opportunity, they now ironically define themselves on the basis of an ideological position on race.

This points to a fundamental reorientation of conservatives away from the social pragmatism of a Deakin or Menzies, towards a series of doctrinal positions on any number of issues: education, industrial relations, social justice, foreign relations and so forth.

Essentially, the history wars approach will be applied to issues of public policy generally. Conservatism will become less its traditional habit and state of mind than a series of incontrovertible positions. On a day-to-day basis, it will be inspired by a successful No case to base itself on negative response rather than positive proposal. It will become, in the true sense of the word, reactionary.

Yet the problem for reaction across Australian history is that while it may convince itself, it will never carry the nation. Australians are radical only in their attachment to moderation. A conservative organism that operates only on its instinctive rejection of the proposals of its opponents would be doomed to perennial failure.

So, the result of the current referendum will involve a great deal more than deciding a particular constitutional issue, or even dealing effectively with the tragedy of our Indigenous people. It will have profound implications not only for future referendums but Australian politics as a whole.

Australians need to think about this as they cast their vote.

Emeritus professor Greg Craven is a constitutional lawyer and former vice-chancellor of the Australian Catholic University.

Referendums are like close grand finals. Two minutes after the final siren, anyone can explain why it was inevitable the victors would win. In reality, it is much harder. One week from polling day, not many would bet their house that the Indigenous voice will win or lose.