The People’s Republic of Xi: China’s helmsman embarks on his second decade in power

Absolute loyalty to Xi is the organising principle of Chinese politics. Now, in devastating detail, the stifling environment in which policy is now made in Beijing has been revealed.

It took Xi Jinping only a few years to make himself the “Chairman of Everything”, the most powerful figure in Chinese politics in the 21st century.

No one predicted his strongman transformation when the “redder than red” princeling was elevated to be the Chinese Communist Party’s comrade numero uno – officially known as its general secretary – at the 18th party congress in November 2012.

Earlier that year Joe Biden, then US vice-president, spent 10 days with China’s incoming leader at the request of president Barack Obama. In a 2013 commencement address at the University of Pennsylvania, Biden recalled briefing Obama on his impressions of Xi: “He’s a strong, bright man, but he has the look of a man who’s about to take on a job he’s not at all sure is going to end well.”

A decade later, on the eve of another party congress, Xi dominates his 96 million member political party and their 1.4 billion subjects. Absolute loyalty to Xi is the organising principle of Chinese politics.

Former prime minister Kevin Rudd, who recently was awarded an Oxford PhD for his study of Xi’s ideology, says we are not even at the halfway point of his reign. Rudd predicts Xi will be China’s paramount leader until 2037.

The 69-year-old Xi’s genes are as robust as they are “red”. His father, a hero of the revolution, lived until he was 89. His mother is 96 and remains in good enough health to dine, chat and stroll with her “dutiful son”, according to Xi’s official biography.

China’s self-regarding “man of destiny” has other reasons to delay retirement. Having overseen the greatest political purge since the bloody Mao Zedong era – with more than 600,000 comrades punished last year alone – stepping down now would be extremely dangerous.

Chris Johnson, the CIA’s former top China analyst, says the speed with which Xi consolidated power over the creaking Leninist machine he inherited is his greatest political achievement.

Xi is now almost seven years into his ongoing period of “leadership supremacy”. There are no credible forms of opposition and no end in sight to his rule.

It makes the upcoming 20th party congress, which begins in Beijing on Sunday, an unusual affair. These week-long, secretive meetings are held every five years. The gatherings of the party’s top 2300 comrades are the most important political conclaves in China. In the pre-Xi era, they were used to introduce the world to the new collective leadership team.

Some of the control-obsessed party’s traditions continue. Instructions once again have been issued to halt work at the steel mills surrounding Beijing to engineer blue skies for the occasion. VPNs have been throttled to restrict access to the “negative energy” lurking beyond the internet beyond China’s Great Firewall.

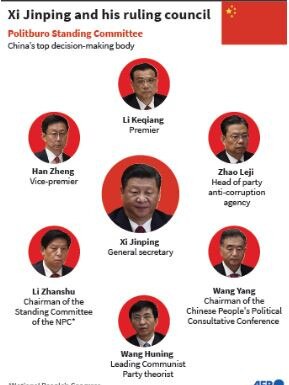

However, this upcoming meeting is expected to be far less momentous than its predecessors. The seven-member standing committee will be reshuffled, as will the 25-member politburo and innumerable positions throughout China’s party state.

These remain significant jobs but, as Xi has returned China to one-man rule, their decision-making influence has fallen dramatically.

“If all of these people are simply ciphers for Xi Jinping, what does it really matter?” asks Richard McGregor, a senior fellow at the Lowy Institute.

An army of Pekinologists is preparing to parse the details that will emerge from Beijing’s black box during the coming days. In their analysis the best of them include the caveat that is the first rule of Chinese elite politics: be aware of how little we know.

Johnson warns international observers against imposing their own wishes on the opaque meeting. Many onlookers dream that the next premier, China’s second highest ranking position, or other senior appointments will moderate Xi’s agenda and adjust his domestic and foreign policy in ways they would prefer – championing economic reform, restraining “wolf warrior” diplomacy, swiftly ending “Covid zero” and a host of other wishes.

Johnson, who has analysed the party professionally for decades, thinks that is fantasy thinking. “There’s no such thing as ‘the saviour premier’,” says Johnson, now a senior fellow at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, DC.

“Xi will remain the major and really the only voice meaningfully in charge of the overall policy direction.”

The previous party congress in 2017 was much more dramatic. Xi used it to signal he was not going anywhere: a startling rupture to the rules of contemporary Chinese elite politics.

In the lead-up to that conclave, Xi purged comrades tipped to succeed him. Months after it ended, he orchestrated the constitutional revision that removed the 10-year limit on China’s presidency.

Susan Shirk, a US deputy assistant secretary of state during the Clinton era, says Xi’s constitutional change prompted the sharpest criticism of a Communist Party leader she has ever heard in almost 50 years covering Chinese politics.

Xi didn’t budge. The wave of retribution against his critics continues. Senior figures in the security state have been taken out ahead of this party congress.

“The purgers are now the purged,” Shirk, chair of the 21st Century China Centre at the University of California, San Diego’s school of global policy and strategy, tells Inquirer.

In her new book, Overreach: How China Derailed Its Peaceful Rise, she writes of her close encounter in 2016 with Xi’s feared Central Commission for Discipline Inspection. She was to meet the deputy director of Beijing’s Taiwan Affairs Office. A phone call came through the night before their meeting, explaining it would no longer take place: he had been arrested.

The official was later sentenced for bribery. Many speculated his real crime was to get on the wrong side of Xi when they were both up-and-coming officials in Fujian province.

In her book, Shirk outlines in devastating detail the stifling environment in which policy is now made in Beijing. Xi discourages the airing of different viewpoints at meetings. Comrades are to bring their concerns to him separately, if they dare. Much of his subordinates’ time is spent trying to outdo each other with praise for the “helmsman”.

The head of Xinhua, China’s official news agency, promised in the months before the coming party congress not to stray from Xi’s instructions for “one minute”.

Xinhua’s “biggest political advantage and primary political task” would be to propagate Xi’s political thoughts, said its fawning editor-in-chief, Fu Hua.

It is not an ideal environment for good policymaking.

“For over a decade, Xi has lived in an echo chamber of head-nodding agreement,” Shirk writes.

She argues that the “bandwagoning” of supplicant advisers has resulted in a sharp deterioration in the quality of domestic and foreign policy decision-making, which has worsened across Xi’s reign. “No one dares tell him about the harmful consequences of his policies.”

A far from complete list of the policies she deems harmful includes China’s combative wolf warrior diplomacy, the country’s ongoing “Covid zero” fanaticism, the horrendous human rights atrocities in Xinjiang, Beijing’s snuffing of Hong Kong, the ferocious attack on China’s tech giants and the “blank cheque” Xi gave to Vladimir Putin ahead of the Russian President’s Ukraine invasion, something even Beijing’s favourite American, Henry Kissinger, has recently criticised.

For all Xi’s power, Shirk sees a leader still pulsing with insecurity. She thinks that is not without reason. In her analysis, Xi’s suffocating leadership style and total refusal to share power looks increasingly unsustainable.

“I definitely think something will happen in the next five years,” she says.

Likewise, Johnson cautions that while Xi is in his moment of “leadership supremacy”, things can happen. He says we should “keep our minds open” to several leadership transition scenarios – including crises – that could still occur during the next five or 10 years of China’s “great rejuvenation”.

He is also blunt about another obstacle to Xi ruling into the late 2030s. “He could die,” Johnson says. “He is obese. He was, and may still be, a long-term smoker. And he has a very stressful job. So if you’re in the actuarial business, you know, you’re wondering.”

Xi’s deeply ideological world view and prickly nationalism make him a foreign policy dilemma for liberal democracies.

“He has … a Marxist-inspired belief that history is irreversibly on China’s side and that a world anchored in Chinese power would produce a more just international order,” Rudd writes in a new essay in Foreign Affairs. The former Labor prime minister’s analysis on Xi is closely read by the Biden administration and governments around the world, including that of his former deputy, Anthony Albanese.

Rudd argues that, whatever liberal-democratic leaders might think, Xi sees himself as being in a grand struggle with them – one in which he is buttressed by “the forces of historical change”.

Xi’s extended reign has introduced further challenges for countries such as Australia that have fallen out with his China. Before him, a leadership change in Beijing might have assisted with moving beyond past slights.

Albanese is the sixth Australian prime minister of the Xi era. As it has gone on, some have watched Canberra’s “pushback” with admiration.

Johnson says Australia has shown that even economically enmeshed middle powers can challenge Xi’s China when the terms are unacceptable.

“I actually think Australia’s been brave and smart,” he says.

Shirk cites Xi’s coercion campaign against Australia as one of the top foreign policy overreaches that have derailed what Beijing used to call its “peaceful rise”.

But she advises countries dealing with China to also keep long-term objectives in mind. They should beware they don’t overreact. “Everything we say and do toward China reverberates through Chinese society and shapes public sentiment,” Shirk says.

McGregor, author of The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers, cautions Australia and its allies to beware of exaggerating China’s international isolation.

“You know, they might be isolated in the Anglosphere. They might be isolated in Europe. They might be isolated in Japan. But if you look around the world, it’s not really the case,” he says.

China’s diplomatic victory in the UN Human Rights Council, where it brazenly shut down debate on a UN-authored report into Beijing’s human rights abuses in Xinjiang, is one recent point of evidence. The scramble of international visitors who will soon head to Beijing to mark Xi’s second decade in power is another. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz is scheduled to arrive early next month. France’s President Emmanuel Macron will follow soon after.

“He wants, I think, something like a coronation ceremony where the leaders of the world come to Beijing to pay tribute … like Napoleon,” a senior diplomat told The South China Morning Post.

The Prime Minister’s first encounter with Xi will come weeks later at the G20 leaders’ meeting in Bali. Whether the two have a separate bilateral meeting is a subject of ongoing discussion.

Comments Xi made to then German chancellor Angela Merkel early in his reign give an indication of his approach should such a meeting happen.

At a getting-to-know-you dinner, her former top foreign policy adviser, Christoph Heusgen, recently recalled, the chancellor had brought up foreign relations with smaller countries. Merkel told Xi that Germany’s history taught it to be generous to its neighbours.

Xi responded by saying China’s history had taught him a different lesson: “We never give ground.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout