‘Get me out of here’: China’s expat exodus

It took three days in ‘Covid jail’ in Shanghai for Australian Mason and his girlfriend to decide they were done with China. They are joining a historic exodus.

It took three days in “Covid jail” for Australian expat Mason and his girlfriend to decide they were done with China.

The bus trip back to their Shanghai apartment didn’t change their minds.

Barricades surrounded the city’s famous old lane houses. Shops and parks were boarded up.

Volunteer Covid quarantine workers were camped out on the streets. One, wearing a white hazmat suit in the 30-plus heat, slept on the pavement surrounded by cardboard boxes.

“Is this actually happening?” Mason, who had been teaching English in Shanghai, asked his girlfriend in disbelief.

Mason, who like most people The Australian spoke to, asked not to use his full name, spent nine days in what the Chinese call a “fangcang hospital”, which translates as a “square-cabin hospital”. (Mason prefers the term “Covid jail”.)

As soon as they have found a home for their six cats, the Melburnian and his girlfriend will join a historic expat exodus.

Up to half China’s expats have left the country since the start of the pandemic.

Jorg Wuttke, the Beijing-based president of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China, thinks that population will halve again by the end of the Chinese school year – only two months away.

That will leave about a quarter of the pre-pandemic expat population. Many of the rest are weighing their options.

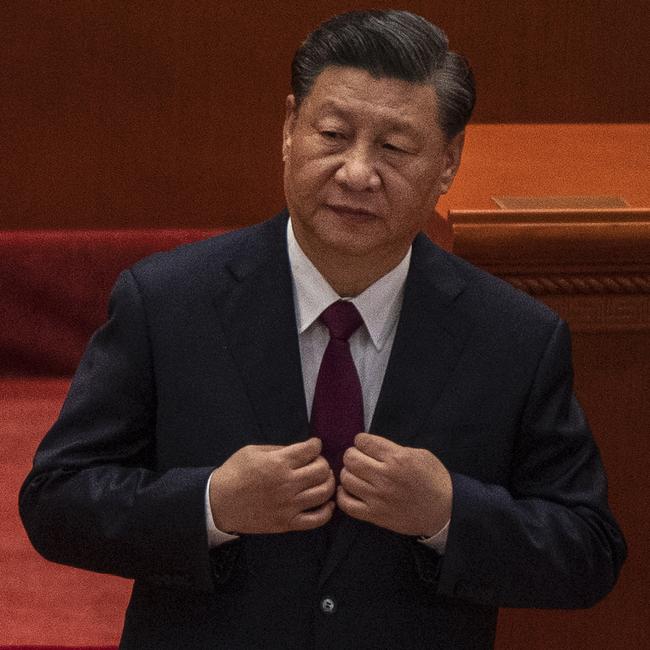

China’s hardline Covid-zero policy is tangled up with President Xi Jinping’s leadership.

The President has repeatedly boasted that China’s approach has demonstrated the superiority of its one-party rule to the “chaos” of the democratic world. That makes changing it almost impossible – especially before Xi gets a third, five-year term at the end of the year.

“They are prisoners of their own narrative,” Wuttke said last week in an unusually frank interview with business publication The Market.

“It’s rather tragic. China was the first to get into the pandemic, and it’s the last to get out.”

Amateur hour

After spending much of the last decade on and off in Shanghai, Mason has a pretty high threshold for chaotic Chinese bureaucracy. “Covid jail” was something else.

The incompetence was staggering.

“Nobody really knew what they were doing,” he says.

Everyone who gets Covid in Shanghai – even those with mild symptoms like Mason and his girlfriend – has to go to an offsite quarantine centre.

Shanghai’s officials are still finding almost 10,000 new cases a day, so the centres keep filling.

Most quarantine centres are much worse than where Mason and his girlfriend were summoned at almost 2am.

About 600 people were packed in the giant shed. On arrival, about 24 of the portaloos were usable. Within days, only eight were, and even those were often nearly overflowing.

There were no showers, although there was a hose. They saw a doctor only once during the whole nine-day stay.

People in hazmat suits – called Big Whites in China – would roam around the centre and concrete outdoor area, spraying bleach into the air.

The day began with orders shrieked over loudspeaker, starting as early as 5.30am.

“Don’t come and ask us for breakfast! … Don’t move the beds! … Don’t stand on the toilets!”

None of the staff could speak English, so Mason – fluent in Mandarin – would translate to the other foreigners.

One was an unlucky German who had been sent to the quarantine centre on the final day of a 10-week short-term contract in Shanghai.

Just after the German – who was triple vaccinated with Pfizer – joined a crowded bus to take him to the quarantine centre, he received a call from the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. There had been a mistake. His test had actually been negative.

It was too late. Now that he was surrounded by people infected with Covid, he had to go to the quarantine centre to serve his sentence.

Losing it

Like all inmates in the centre, Mason was known by his bed number. His was “E 1-044” – “E-44” for short.

On day nine, inmate “E-44” lost it.

His girlfriend had been told she would leave the day before, but her bus did not come.

Mason, who by now also had consecutive negative tests, went to the reception desk to ask why it hadn’t come.

“We don’t know,” the nurse said.

What about Mason: when was he leaving?

“Maybe you’ll go home tomorrow. Maybe not.”

After nine days trapped in a Kafka novel with Chinese characteristics, he snapped.

“I absolutely went crazy … Yelling, screaming, shouting.”

Mason called his mother in Melbourne on video chat. She told him to calm down.

She came up with the idea to tell the quarantine camp official’s that the family had been in touch with Australian media. (They hadn’t.)

If they didn’t let him out today, they would do a live-stream from the camp. It would not be a good look, they suggested.

Within hours, he and his girlfriend were on a bus that took them back to their apartment – through the ghostly scenes of Shanghai’s war on Omicron.

It was a relief to be going home, even if they wouldn’t be allowed to leave except when summoned for their daily Covid tests.

Their neighbours were audibly less happy.

There was yelling and screaming once they realised Mason and his girlfriend had returned.

“They were positive!” shouted one panicked neighbour.

Mason can understand their anxiety.

“They’re not so scared about getting Covid. They’re more scared about being sent to one of these fangcang.”

How to leave Shanghai

For Lena, an Australian freelance artist, it took a fortnight of Shanghai’s total lockdown to decide it was time to leave.

The entire pipeline of her work in China had collapsed.

She judged it wouldn’t come back for six months, perhaps longer.

Like thousands of others, she joined a WeChat group that shared tips on how to get out of China. The path is difficult and expensive.

She has seen the airport cab fare as high as $1000 (5000 RMB).

“There are all these layers of stress,” she tells The Australian from the old lane house she has been confined to for a month, with no end in sight.

Another longtime Shanghai expat said her family will leave as soon as they could get into a bank branch to settle their finances.

Those fleeing now need to get permission to leave their compound.

Many require residents to sign forms saying that once they leave, they will not be allowed to return to their home – whether or not their plane takes off.

Flights are scarce.

Australia’s consul-general in Shanghai, Dominic Trindade, said on a recent video call with Australian expats that the government had no plans to organise any Wuhan-style emergency flights.

Lena has a one-way ticket to Australia via Singapore Airlines. Her flight leaves in mid-May.

That means, if all goes to plan, she has only another fortnight of being woken by local government workers shouting instructions through loudspeakers as they roam the neighbourhood.

“Don’t hug the people in your house! … Don’t eat together!”

The bellowing starts as early as 6:40am.

“It’s like a form of audio torture,” Lena says, laughing.

She’s always enjoyed the “quirkiness” of China. But Shanghai, in the third year of the pandemic, has gone way beyond quirky.

“It’s like the heart has been ripped out of the city,” she says.

‘Do not come to China’

International investors are looking on in horror.

Weijian Shan, the founder and chair of one of Asia’s biggest private equity investors, last week said the Chinese economy was in its worst shape in 30 years.

“China feels to us like the US and Europe in 2008,” said Shan, whose Hong Kong-based investment group PAG manages more than $70bn.

Australian businesses have already been pummelled by Beijing’s black-listing of more than $20b of annual exports, including coal, wine, lobsters and barley. Now this.

“There’s a high level of concern,” says Nick Coyle, the chief executive of AustCham China, which is based in Beijing.

Many of the industry body’s members in Beijing and around the country are nervously watching the situation in Shanghai.

Sister outfit AustCham Shanghai would not comment on the ongoing lockdown. But, saying she was speaking in a personal capacity, AustCham Shanghai’s chair Heidi Dugan strikes a more optimistic tone.

Departing Europeans and Americans creates opportunities for those who stay, she tells The Australian.

“In crisis, there’s always an opportunity,” says Dugan, who has a cooking show on Chinese television and is director of Arete Group, a China-focused business advisory group.

“Now is the time to sharpen the sword. Now is the time to step forward and grab this opportunity to be amazing,” she says from her Shanghai apartment.

Others in Shanghai are advising potential new residents to keep well away.

A week ago, a German asked a Shanghai expat group on Facebook about the situation in the city.

He had an offer for a job in Shanghai and planned to bring his young family in the coming months.

The forum erupted with disbelief: “Don’t come … Don’t do it … Run away!!!!”

He was urged to consider the perilous situation of Shanghai’s international schools.

“If you’re coming to teach, be aware that schools are being less than truthful because they are desperate for staff,” one warned.

A Shanghai-based American with a toddler was more blunt.

“Do not, I repeat, do not come to Shanghai or China,” he advised.

“Go anywhere else.

“Start putting China in the same category as North Korea.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout