Fall and rise of China’s Xi Jinping, leader who bent country to his will

The Chinese president is setting himself up to rule for life. It was the teenage years spent lugging manure around the countryside that made him the man he is.

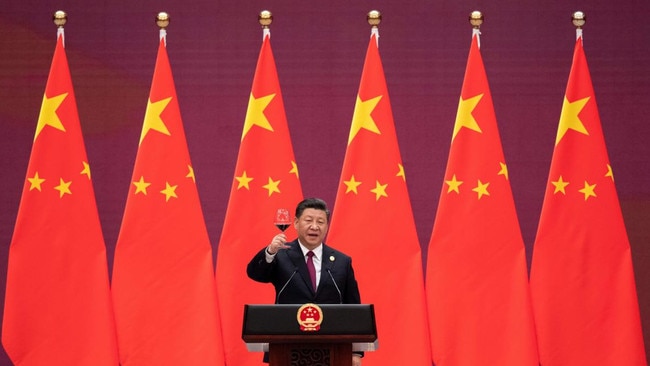

In the space of a decade, President Xi Jinping of China has steadily and unstoppably become the most powerful and important leader in the world.

About his power, there is little argument: unconstrained by democratic accountability or any limit to his term, he controls a country of 1.4 billion people. He commands the world’s largest armed forces and directs an economy that will in the next few years go from second place to overtake the United States as the biggest in the world.

Under Xi, China has gone from the status of rising regional power to superpower in waiting, and it has done so faster and more aggressively than almost anyone anticipated. He has also created something more surprising for a Chinese leader: a distinctive image, both at home and abroad.

After the reformist Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese Communist Party was led by restrained and self-effacing men who projected the blandness of collective leadership. Xi, by contrast, is an individual with a distinct and powerful personality, who also succeeds in standing for modern China, in all its accumulating power and menace.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s sullen smirk is still more familiar to people in the West, but the figure of Xi is becoming one of the defining images of the age: portly, straight-backed, famously likened on social media to Winnie the Pooh, but with a sour smile and air of dyspeptic irritation. He has reinforced the CCP’s position at the centre of Chinese politics. Under his aegis, China has locked up the government’s opponents and critics, repressed political freedoms in Hong Kong, and incarcerated a million Muslim Uighurs in internment camps in Xinjiang province.

The People’s Liberation Army has turned disputed rocks in the South China Sea into Chinese military bases, and intensified its threat to invade other territories claimed by Beijing, including Taiwan.

Xi has abolished any limit to the term of his job, leaving the way open for him to be leader for life. In just over a week he will almost certainly renew his lease on power for another five years, at this month’s national congress of the CCP.

It is a statement of the obvious to call him an authoritarian; to plenty of western commentators he is an out-and-out dictator. Xi did not spring out of nowhere, however, to impose himself from above. Whatever changes he has brought to his party and his people, he has also been formed by them and by his own, sometimes traumatic, past.

“Xi himself seems to exemplify power,” writes Kerry Brown, professor of Chinese studies at King’s College London, and author of Xi: A Study in Power. “It exudes from him almost like a physical force.”

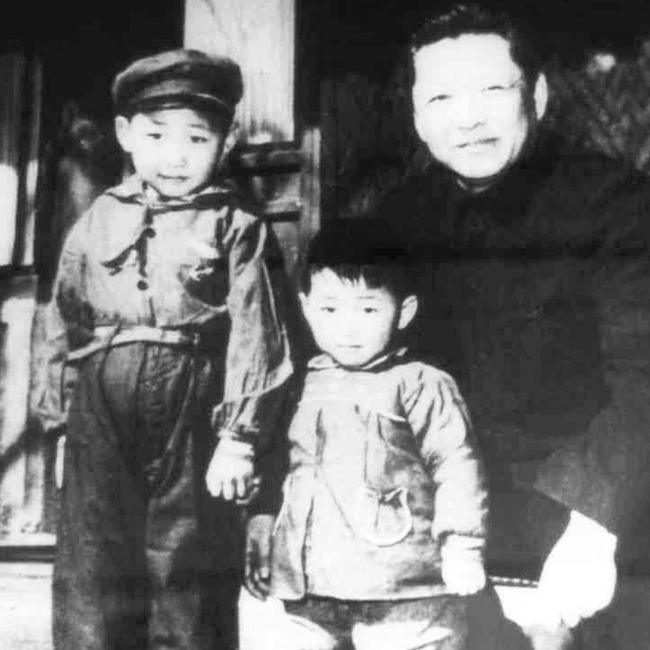

No one who knew the young Xi would have predicted his ascent to supreme power. He was born in 1953 into the communist aristocracy, the son of Xi Zhongxun, a revolutionary hero who became a vice-premier under Mao. In 1962, Xi Snr was accused of plotting against the party, and he spent the years until Mao’s death in 1976 in jail or under surveillance.

His son went overnight from being a “princeling” to the spawn of a counter-revolutionary. The family home was ransacked by Red Guards and the family was scattered, with the strain driving his older half-sister, Heping, to suicide. At the age of 15, Xi was trucked out of Beijing to work in the fields.

He spent seven years in Shaanxi province, suffering the indignities of dirt, fleas, cold and hard manual labour. But it was the making of him.

Xi’s years humping manure have become a crucial element in his personal mythology. A British equivalent is hard to pin down but, it is rather as if an Old Etonian was to go into Westminster politics after living among pig farmers in Sherwood Forest.

In his later writings, he is frank about the hardships of that time: “The knife is sharpened on a grinding stone and a man is made through hardships.”

Far from instilling in him a hatred of the system, it made him all the keener to rejoin it. Nine times he applied for party membership and was rejected; the tenth time he got in.

In Yanan, he became an omnivorous reader: in between tending the goats, he studied Marx, Engels, Hegel and Henry Kissinger, and once walked 32km to borrow a copy of Goethe’s Faust.

Ludicrous intellectual name-dropping has been a characteristic of his oratory ever since: in one speech in 2014, Bougon records, he referred to 114 Chinese and foreign painters, calligraphers, philosophers, musicians, dancers, choreographers, sculptors and writers.

At Tsinghua University in Beijing, however, he chose to study engineering rather than literature. He spent three years as aide to a PLA general, then switched to civilian party posts. In 1987 he married his second wife, Peng Liyuan, a patriotic folk singer known as the Peony Fairy.

By Xi’s own account, his early years imparted to him the toughness that is obvious today. But he also acquired an instinct for staying out of trouble in a Chinese political world that was deeply and corruptly enmeshed with business.

Fujian province, where Xi became governor, was worse than most. At the turn of the century, it was engulfed in a huge scandal centring on Lai Changxing, a billionaire businessman and smuggler who was eventually given a life sentence for $US5 billion of bribes. A total of 300 others were convicted and 14 sentenced to death. Xi sailed through unscathed.

He established a rule that no members of his family should do business in the provinces where he worked; a strikingly principled position in a country in which high political office was often a means of enrichment for entire clans.

By 2007 he was vice-president. Four years after that he succeeded the uncharismatic Hu Jintao as party leader, and quickly had himself named president.

A murky scandal involving the murder of Neil Heywood, an Old Harrovian businessman, saw off one rival, Bo Xilai, and the anti-corruption drive that he set in motion has put many potential challengers on the defensive.

He has never had to conduct a conventional party purge, but those who, in different ways, have embarrassed or challenged the government have been locked up or forced out of circulation, from human rights lawyers to the tennis player Peng Shuai, who accused a top party man of coercing her sexually.

Outside China, Xi has made himself notorious for his suppression of human and political rights in Xinjiang and Hong Kong.

But within the country, he deftly positioned himself as “Xi Dada”, or Uncle Xi, a down-to-earth figure who, during a campaign against wastefully lavish entertaining by party cadres, was photographed queuing to be served at a humble steamed-bun restaurant.

Beneath the image-building, several consistent themes emerged. Surprisingly, for a man who suffered personally from the excesses of that era, he has revived respect for Mao, whom he admires for his peasant simplicity and revolutionary discipline, and his insistence on the primacy of the party.

His second intellectual prop, however, is a figure despised by Mao: Confucius, the 6th-century BC sage whose teaching insists on hierarchy, obedience, and reverence for elders. To push the Great Helmsman with one hand and the Great Sage with the other is nonsense in theoretical terms – but together they serve to justify a repressive authoritarianism that rejects the mildest concession to more representative forms of government.

To further confuse the intellectual picture, Xi has defended global capitalism and the Paris climate treaty against the protectionist scepticism of Donald Trump.

It would be going too far to glamorise this jumble of ideas with the label ideology.

Xi’s most important policy is not an expression of political thought so much as sheer ambition: China 2049 or the “Chinese Dream”, the goal of restoring unambiguous prosperity and international greatness by the CCP’s mid-century centenary.

There is still plenty that could go wrong. If he does stay in for life, then Xi must make good on his promise to reunify Taiwan, a tremendously risky gamble if attempted by military force. Well before it reaches 2049, China will have to complete the transition from a low-wage manufacturing economy to services, at a time when powerful and unpredictable winds are battering even the strongest economies.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout