Wolves in the weeds as Beijing’s harsh diplomacy backfires

Looking tired and anxious, Beijing’s ambassador Cheng Jingye has almost entirely retreated from Canberra’s diplomatic social scene. It turns out enemies are everywhere.

Beijing’s man in Canberra, ambassador Cheng Jingye, looked tired and anxious.

There is a lot to worry about in the paranoid Xi Jinping era, especially for a cosmopolitan United Nations specialist like Cheng. For China’s diplomats, potential enemies are everywhere, inside and outside their walled compounds. Every encounter is a test of loyalty – and all recorded on their embassy’s or consulate’s Hikvision surveillance equipment.

“There’s a second Cultural Revolution going on,” says one senior Canberra-based diplomatic source, who agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity.

Once-common motions within the Canberra diplomatic community – such as a new ambassador paying a courtesy visit to their counterpart at the Chinese ambassador’s residence in Yarralumla – have now become fraught with risk.

In one such recent exchange, a new ambassador found that a junior Chinese diplomat sat by the worried-looking Chinese ambassador for the whole meeting, taking notes.

A subsequent invitation for a relaxed dinner was rejected. Cheng’s secretary cited “Covid” despite Canberra not having had a single domestic case for months.

One fellow ambassador says Cheng, 61, has almost entirely retreated from Canberra’s diplomatic social scene.

“In a situation like this, they need to be communicating. But instead they are isolated,” the ambassador tells Inquirer, saying the situation was similar at posts around the world.

“When things get difficult, they don’t answer. They close communication channels.”

Outside Canberra, the ambassador’s colleagues in the Chinese Foreign Ministry have called the Prime Minister of Canada, Justin Trudeau, a “running dog”, spread a conspiracy theory that the coronavirus was imported to Wuhan by the US army and, in Fiji, concussed a diplomatic representative from Taipei.

That last act of violence was triggered by a cake decoration: the Taiwanese flag, in miniature.

“A lot of this behaviour comes from insecurity,” says Peter Martin, the author of a new book called China’s Civilian Army, a sometimes disturbing and often hilarious study of PRC diplomacy.

“Individual diplomats find themselves in this very strange position where their country is stronger than it has ever been, but their place in the political system is as tenuous as it has been in decades,” the Bloomberg reporter tells Inquirer over the phone from Washington DC, his new base after a long stint in Beijing.

From ‘silver fox’ to wolf warrior

Things could be worse. During the frenzy of the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s, Chinese diplomats demonstrated their loyalty to Chairman Mao by beating up German diplomats in the streets. The Czechoslovakian ambassador was detained at an airport.

“Most dramatically, the British mission in the Chinese capital was stormed and torched by Red Guards,” Martin writes in his absorbing book.

When protests broke out outside the Chinese embassy in London, young Chinese diplomats engaged in hand-to-hand combat with the protesters. “British television news captured an image of a Chinese diplomat waving an axe,” Martin records.

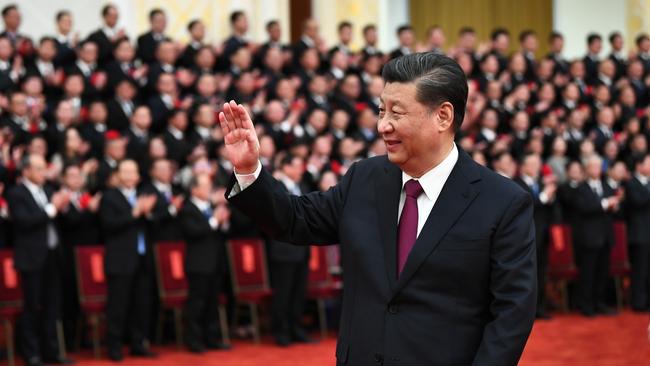

Axes haven’t yet reappeared under Xi, but he has overseen a sharp new approach to asserting Chinese interests abroad. Capitals around the world took years to understand the change, which occurred in Beijing just months after Xi was anointed China’s President in March 2013.

Julie Bishop encountered the new era on her first visit to Beijing as Australia’s foreign minister in December 2013. Her meeting with China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi was one of the first examples of what was later dubbed “wolf warrior” diplomacy – named after a 2017 jingoistic action film that was the Chinese movie industry’s answer to Rambo.

In front of a media pack, the normally smooth-talking Wang – dubbed the Chinese equivalent of a “silver fox” by state media – erupted over comments Bishop had made before the trip.

Australia’s foreign minister had made a mild criticism of Beijing’s declaration of an air defence identification zone in the disputed East China Sea.

“It felt like an ambush,” Bishop tells Inquirer. “We certainly had no briefing or warning that it was coming.”

With hindsight, it was a seminal moment in China’s new approach to Australia. And it took place years before Canberra’s banning of Huawei from its 5G network, the passage of legislation aimed at China’s brazen interference in Australia’s political system, or the Morrison government’s call for an inquiry into Covid-19.

Reliving Wang’s public tirade before a Senate estimates hearing two months later, senior Australian foreign affairs official Peter Rowe said he had “never in 30 years encountered such rudeness”.

The profound shift in China’s dealings with the world was little understood by the Australian government. This included Australia’s then ambassador in Beijing, Frances Adamson, who is soon to leave her role as head of the Department of Foreign Affairs.

The Mandarin-speaking Adamson’s bafflement was summed up in a note she passed Bishop as she waited for Wang’s lecture to be translated. It read: “This is going terribly badly.”

As Martin reveals in his book, the episode derived from the fear Xi had instilled in China’s foreign ministry. They had a reputation in China for being soft – in need of calcium pills to toughen up their spines. Communist Party general secretary Xi wanted that ailment fixed. He demanded a foreign ministry with “fighting spirit”.

“Wang’s solution was to double down on the founding values of the ministry,” writes Martin.

“After all, it had been set up to help a closed and paranoid political system cope with a more open outside world. Many of these founding principles were perfectly suited to the emerging mood in Beijing.”

Wang had made as much clear four months before dressing down Bishop. In a speech given in August 2013, Wang said China’s diplomats needed to embrace the guiding principles of Mao’s suave premier and wily foreign affairs adviser Zhou Enlai.

“(Zhou) famously said that diplomats are the People’s Liberation Army in civilian clothing,” Wang told his department of soon-to-be wolf warriors. “A civilian army not only needs to maintain strict discipline and obedience to commands, but also needs to cultivate a strong character and work style … to serve the people like the PLA.”

They haven’t stopped fighting since.

Some are worried that Xi has taken it too far

Eight years on, with the wolf warrior volume turned up to 11, there is grumbling in Beijing about China’s anti-diplomatic diplomacy. Some voices have even suggested that China may have clubbed Australia a bit too hard.

Last December, Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian caused a diplomatic storm by tweeting a provocative artwork of an Australian soldier murdering an Afghan child.

The popular nationalist blogger Ren Yi – who writes under the pen name “Chairman Rabbit” – told his more than two million fans on Chinese social media that Zhao’s approach was not helping China. Ren even suggested the pugnacious Zhao had been unknowingly “Trumpised”, a cutting insult in Xi’s China.

“This is very dangerous,” wrote the Beijing-based, Harvard University-educated princeling.

While he agreed uppity Australia was a deserving target for a few “pokes”, he argued worsening China-Australia relations would hurt China. It would make the new Biden administration tougher on China.

“Regarding this dispute between China and Australia, the author believes that China should cool down now. After all, Biden’s primary goal is to repair the relationship with allies, not to repair the relationship with China.”

It was not one of Ren’s better-received posts. Most of China’s nationalistic netizens were on Zhao’s side. But the China-heavy agenda at this weekend’s G7 summit in Cornwall suggests Ren had a point, as do the invitations given to Australia, India and South Korea – three countries that have been on the receiving end of Xi’s assertive approach.

Scott Morrison is particularly keen to discuss matters with fellow “like-minded” countries after more than 12 months of Chinese trade attacks.

Even Xi seems to think it is time for some tinkering.

At a politburo study session last week, he told his senior colleagues that China needed to tell its story better and win the struggle to be more “loveable”.

“It is necessary to make friends, unite and win over the majority, and constantly expand the circle of friends (when it comes to) international public opinion,” he told the politburo, according to China’s official news agency Xinhua.

Diplomacy vs the cult of personality

China’s Paramount Leader is clearly frustrated with the country’s image in the developed world. But there is no indication that his anxious diplomats – in Canberra and elsewhere – will be allowed to do their jobs in a less rigid, more flexible manner.

Creative diplomacy is the antithesis of a cult of personality or the “self-criticism” sessions that are the hallmarks of the Xi era.

Martin says that while people should be open to the possibility that Beijing will change its approach, the cause of tensions between China and the developed world go far beyond diplomatic niceties. There’s Xi’s abolition of term limits. There’s his extraordinary crackdown on dissenting voices. And there’s the obsession with Marxist ideology, Leninist control and Xi’s own brilliance – including his hardline and “totally correct” approach to dealing with Uighurs in Xinjiang.

“I’m not sure there’s any way even the most skilled Chinese diplomat could sell those policies to a Western audience in a way that would be persuasive,” says Martin.

While the big picture is uncertain, the small stuff is much more clear: China’s civilian army is going to keep sweating about it.

In recent years, China’s diplomats have busied themselves defending the motherland’s honour against claims by South Korea that it invented fermented cabbage, “so-called kimchi”.

Others have demonstrated Beijing’s might by storming out of a meeting when the President of Nauru (population 13,000) let the Prime Minister of Tuvalu (population 12,000) speak before the representative of China (population 1.4 billion).

Martin says one of the key lessons of his more than four years of research for the book – which draws on scores of never-before-translated autobiographies – is that for Chinese diplomats, there is no such thing as a low-stakes encounter.

“We have this image that Chinese statesmen think in decades, not years. They are strategic and not caught up in tactics,” he says.

“But when you read these memoirs and you listen to accounts of these events, you realise, no, they are deep in the weeds – all the time.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout