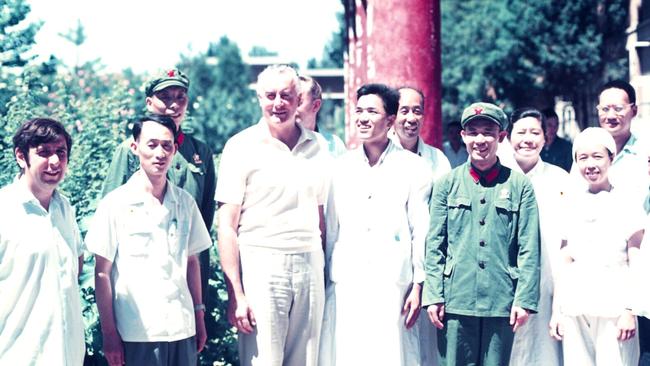

When Gough Whitlam arrived in Peking just before midnight on July 3, 1971, it was the beginning of a journey of high political adventure and political risk with profound consequences for Australia.

The history-making visit by the then opposition leader with a Labor delegation took place 50 years ago next week. This visit, condemned by Billy McMahon’s Coalition government, paved the way for diplomatic recognition of the People’s Republic of China on December 21, 1972.

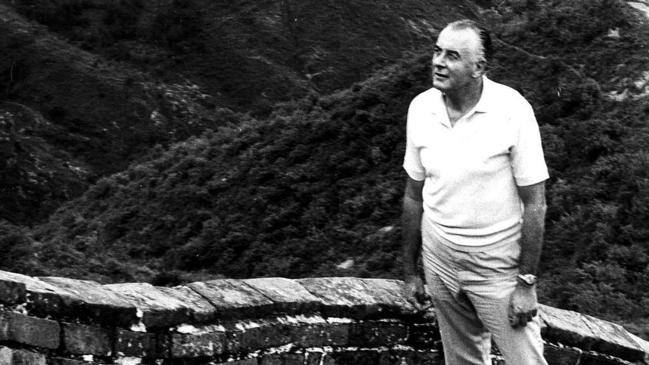

The visit culminated in a late-night meeting with premier Zhou Enlai in the Great Hall of the People on July 5, witnessed by a bevy of Australian journalists, as the Australian Labor leader and the Chinese premier conducted a tour d’horizon of geopolitics.

It was the week that changed the world. On the day Whitlam left Peking (now Beijing), on July 9, US national security adviser Henry Kissinger arrived for secret talks with Zhou. A week later, president Richard Nixon announced that he would go to China with the purpose of normalising relations.

This newspaper partly funded the delegation’s visit to China – picking up the airfares for press secretary and speechwriter Graham Freudenberg – and in return Whitlam wrote a series of exclusive reports for The Sunday Australian. No other newspaper gave it such extensive coverage or viewed it so positively.

Stephen FitzGerald is the last surviving member of the delegation. Fluent in Mandarin, he was appointed Australia’s first ambassador to China after diplomatic relations were re-established when the Whitlam government came to power the following year.

“It was high risk but this was a matter of political judgment, leadership and courage,” FitzGerald, 82, tells Inquirer. “And there was an element of luck because, as we know, after Whitlam’s meeting with Zhou, Kissinger arrived on his secret visit to Beijing.

“Whitlam was very attentive to international relations. There were signs the US might be about to move on China. The Canadian government had recognised China and there were indications that other countries might also be on the move.”

When China failed to renew Australian wheat contracts, Labor’s federal executive resolved that Whitlam should contact Zhou. On April 14, Whitlam telegrammed Zhou that Labor was “anxious to send (a) delegation” to discuss terms for “diplomatic and trade relations” and asked if such a delegation would be received.

On May 10 came the reply, via the People’s Institute of Foreign Affairs, welcoming a Labor delegation. Nobody knew that Zhou was also negotiating the timing of Kissinger’s visit. Zhou, no doubt aware of the significance of a visit from a US ally and a potential Australian prime minister, decided that Whitlam should come before Kissinger.

Whitlam’s adviser, Richard Hall, contacted academic Ross Terrell to help facilitate the visit. Terrill contacted France’s ambassador to China, Etienne Manac’h, who in turn raised it with Zhou.

Terrill , a China specialist, has a new memoir published this month titled Australian Bush to Tiananmen Square (Hamilton).

When Zhou approved Whitlam’s visit, the Labor leader phoned Freudenberg to invite him to join the delegation. Freudenberg later remarked that at the beginning of 1971 he thought it was more likely he would go to the moon than go to China.

The delegation also comprised Tom Burns (Labor’s federal president), Mick Young (Labor’s federal secretary) and Labor MP Rex Patterson.

Nine journalists accompanied the delegation: Philip Koch, Derek McKendry and Willie Phua (ABC), Laurie Oakes (Herald & Weekly Times), Ken Randall (The Australian), Eric Walsh (News Limited), Allan Barnes (The Age), John Stubbs (The Sydney Morning Herald) and David Barnett (AAP).

“There was a great sense of adventure, camaraderie, apprehension,” FitzGerald recalls. “We all got on well together. There were a lot of jokes between us and the journalists. It was almost as though it was one party because we travelled together and we stayed in the same hotels.”

FitzGerald had worked as a public servant and diplomat, visiting China several times, and switched to academe when he began advising Whitlam on China.

When they first met over lunch in 1967, he found the Labor leader had a clear idea about Australia’s relations with China.

“It was quite apparent he knew a lot more about international relations than I did,” FitzGerald acknowledges. “But he really enjoyed having experts around him who had a deep knowledge and deep intellectual engagement and a policy outlook.”

In 1954, Whitlam had urged Australia to recognise China. He advocated an independent foreign policy, within the US alliance framework, and in accordance with the shifting currents of global affairs.

“Whitlam had the attitude that it was rational and logical to seek to have diplomatic relations with Beijing and that it was irrational to claim, as Australian policy did at that time, that the government in Taiwan was the government of the whole of China,” FitzGerald recalls.

“It was really about the realpolitik of our situation and the fact that the Chinese Communist Party was in power and, whatever you thought of it, they formed the government of China and it was there to stay.”

But there were risks in going to China.

First, Labor had long been accused of having sympathy with communism and this was an electoral liability through the 1950s and ’60s. Australia also had troops fighting the Vietnam War and China had aided North Vietnam. FitzGerald says several Labor figures opposed the delegation to China.

Second, there was the possibility that Whitlam would not secure high-level talks with Chinese leaders or any agreement about the wheat trade or providing diplomatic recognition. It could also antagonise the US. Whitlam risked being humiliated on the world stage. Whitlam, ever headstrong, decided to go.

The delegation arrived in China via Hong Kong on July 2. On July 4, after arriving in Peking the night before, they banqueted and conversed with senior government ministers. Whitlam gained assurances on wheat trade and diplomatic relations from ministers. But it was still not known whether he would get a meeting with Zhou.

“Zhou had been the architect of the foreign policy of the Chinese Communist Party since before the time the communists had come to power,” recalls FitzGerald. “He was internationally recognised and known as a very skilled statesman and diplomat. A meeting with Zhou was the prize.”

On July 5, the delegation was told there would be “an interesting film” that evening and they should wear suits. It was later confirmed they would meet Zhou. It was a moment of relief and excitement for the delegation. Just after 9pm, they were driven across an empty Tiananmen Square to the Great Hall of the People. They exited the cars, walked up the steps and along a corridor to the East Room. Zhou, 73, dressed in a shiny grey uniform, greeted them one by one. Australian and Chinese journalists, and Terrill , were already seated. The meeting was organised in a U-shape formation on an elevated platform. It was to be a mix of high summitry and public theatre with an audience.

The talks went for nearly two hours in front of almost 60 people. Zhou began by noting the fortunes of their respective parties. “When your party was in office we had not yet completed the liberation of our country and when the Chinese liberation was complete you were no longer in office,” he said. The two leaders engaged in a frank and direct dialogue that traversed the ANZUS and Southeast Asia Treaty Organisation alliances and the status of US forces in the region; China’s relations with Japan, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Soviet Union and the US; the Vietnam War; and the status and future of Taiwan. Recognising communist China meant withdrawing diplomatic recognition of Chiang Kai-shek’s Taiwan (Republic of China).

The critical exchange between the two leaders came at the end.

Zhou: “What is past is past and we look forward to when you can take office and put into effect your promises.”

Whitlam: “If my party wins the next elections you will be able to see the first visit by (an) Australian prime minister to the Chinese People’s Republic and its sole capital Peking.”

Zhou: “We will welcome it. All things develop from small beginnings. After these 20 years of struggle you will shortly be able to rise up again.”

FitzGerald was relieved. “I could think of no other person in the Australian parliament who had the knowledge and the intellectual capacity, and the skills, to be able to deal with this situation and carry it off in public,” he says. “This was the first meeting between a senior Australian political leader and the Chinese premier since 1949.”

The delegation left for Shanghai on July 9. Two days later, Zhou organised a cake to celebrate Whitlam’s 55th birthday. The Labor leader had emerged from his “journey into the unknown” – as FitzGerald describes it – in triumph. Whitlam was also ecstatic, recalling the trip as “the most exciting and exacting” of his lifetime.

It was McMahon who now found himself on the outer. He lashed Whitlam’s “instant coffee diplomacy” and warned against Australia becoming a pawn of China. “Mr Zhou had Mr Whitlam on a hook and he played him as a fisherman plays a trout,” McMahon chortled. He was humiliated when Nixon’s visit to China was announced days later.

The China that Whitlam visited in 1971 was different to the China in the era of Deng Xiaoping, who led the “reform and opening up” from 1978 that lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. And it is a different China again today, more assertive and authoritarian, under Xi Jinping. While two-way trade with China has underpinned Australia’s economic prosperity, relations have soured to their lowest point since Whitlam’s 1971 visit, argues FitzGerald. He is critical of Coalition and Labor governments for lacking a coherent strategic policy for engaging with China, and laments that relations are now mired in paranoia and panic.

“It is a different China but that does not absolve us of the responsibility of trying to engage with it,” FitzGerald says. “China is now economically bigger, more powerful, but you have to engage with a country like that whatever you think of it. This is what Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Vietnam are doing.”

That, in many ways, is the legacy of Whitlam’s visit to China 50 years ago. On returning to Australia, FitzGerald found that the fear and suspicion about China was being replaced with interest and curiosity. The visit was a catalyst for changing public attitudes. All it required was courage, foresight and, above all, leadership.

“We should be engaging with Beijing at the highest possible level,” FitzGerald says. “It is really important to be talking at the very top to get an understanding of how the Chinese leaders view a range of issues, to see how they respond, and to put our views about our national interests. That is the way to go about it.”

-

During his 1971 trip Gough Whitlam filed a series of articles for The Australian about what he saw, and why he believed so passionately in the need for Australia to develop a relationship with China. They are remarkably resonant today.

Read them here:

Whitlam’s Dateline Peking: Labor’s leader reports from China

-

Troy Bramston has been a senior writer and columnist with The Australian since 2011. He has interviewed politicians, presidents and prime ministers from multiple countries along with writers, actors, directors, producers and many pop-culture icons. Troy is an award-winning and best-selling author or editor of 12 books, including Gough Whitlam: The Vista of the New, Bob Hawke: Demons and Destiny, Robert Menzies: The Art of Politics and Paul Keating: The Big-Picture Leader. Troy is a member of the Library Council of the State Library of NSW and the National Archives of Australia Advisory Council. He was awarded the Centenary Medal in 2001.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout