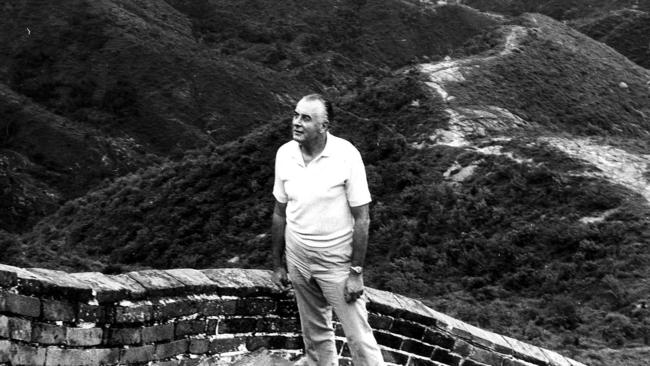

Gough Whitlam: my mission to China

If this visit helps achieve a breakthrough to reality, I shall judge it a success. I want Australia to have a real future in this region. That is why I am here.

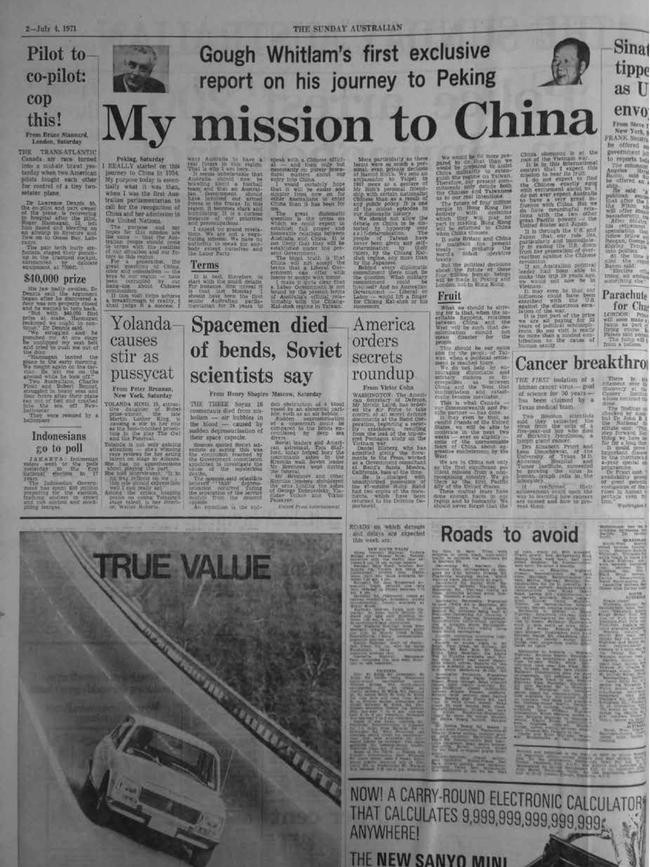

Gough Whitlam’s first exclusive report on his journey to Peking, published in The Australian on July 4, 1971.

I really started on this journey to China in 1954. My purpose today is essentially what it was then, when I was the first Australian parliamentarian to call for the recognition of China and her admission to the United Nations.

The purpose and my hopes for the mission are the same – that the Australian people should come to terms with the realities of our situation and our future in this region.

For a generation, the great questions of China, colour and colonialism – the keys to our region – have been corrupted by our hang-ups about Chinese communism.

If this visit helps achieve a breakthrough to reality, I shall judge it a success. I want Australia to have a real future in this region. That is why I am here.

It seems unbelievable that Australia should now be brawling about a football team and that an Australian Government should have involved our armed forces in the fracas. In this region, it becomes stark and humiliating. It is a curious measure of our priorities and preoccupations.

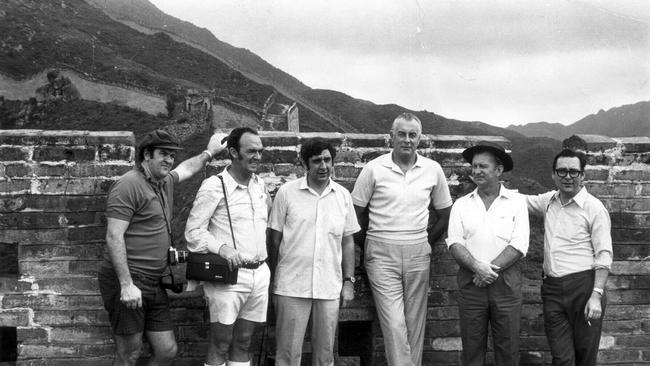

I expect no grand revelations. We are not a negotiating mission. We have no authority to speak for anybody except ourselves and the Labor Party.

Terms

It is best, therefore, to start with the small details. For instance, how unreal it is that last Monday I should have been the first senior Australian parliamentarian for 24 years to speak with a Chinese official – and then only but necessarily on purely procedural matters about our entry into China.

I would certainly hope that it will be easier and simpler from now on for other Australians to enter China than it has been for me.

The great diplomatic question is the terms on which we could expect to establish full proper and honourable relations between Australia and China. It is not likely that they will be established under the present Government.

The blunt truth is that China will not accept the terms that a Liberal Government can offer with honour or can accept with honour.

I make it quite clear that a Labor Government is not bound by the present terms of Australia’s official relationship with the Chiang-Kai-shek regime in Taiwan.

More particularly as these terms were so much a personal, even private decision of Harold Holt’s. We sent an ambassador to Taipei in 1967 more as a gesture of Mr Holt’s personal friendship with certain nationalist Chinese than as a result of any public policy. It is one of the oddest episodes in our diplomatic history.

We should not allow the debate on China to be distorted by hypocrisy over self-determination. The people of Taiwan have never been given any self-determination by their rulers, by the Chiang Kai-shek regime, any more than by the Japanese.

Behind every diplomatic commitment there must lie the question: What military commitment could be involved? And no Australian Government – Liberal or Labor – would lift a finger for China Kai-shek or his successors.

We would be no more prepared to do that than we would be prepared to assist China militarily to extinguish the regime on Taiwan. Therefore, our present commitments only delude both the Chinese and Taiwanese as to our real intentions.

The future of four million people in Hong Kong lies entirely with decisions which they will play no part in making. Hong Kong will be returned to China when China chooses.

It suits Britain and China to maintain the present treaty – probably the world’s oldest operative treaty. But the political decisions about the future of these four million human beings will be made in Peking and London, not in Hong Kong.

Fruit

What we should be striving for is that, when the inevitable happens, relations between China and the West will be such that decolonisation should not mean disaster for the people.

This should be our same aim for the people of Taiwan when a political settlement is reached there.

We do not help by encouraging diplomatic and military stances so incompatible as between China and the West that confrontation and catastrophe become inevitable.

This is what Canada – our Commonwealth and Pacific partner – has done.

It may even be that as candid friends of the United States, we will be able to moderate in the next two weeks – ever so slightly – some of the unreasonable fears of China about aggressive encirclement by the West.

We are in China not only as the first significant political mission from a non-recognising country. We go there as the first Pacific ally of the United States.

These mutual fears have done enough harm in our region and to humanity. We should never forget that the China obsession is at the root of the Vietnam War.

It is in this international context that I expect this mission to bear its fruit.

I do not expect to find the Chinese exactly agog with excitement about us. I do not ever expect Australia to have very great influence with China. But we do have meaningful relations with the two other great Pacific powers – the United States and Japan.

It is through the U.S. and Japan that our role lies, particularly and immediately in easing the U.S. down from her generation of over-reaction against the Chinese Revolution.

If an Australian political leader had been able to make this trip 10 years ago, we would not now be in Vietnam.

It may even be that our influence could have been exercised with the U.S. against the disastrous escalation of the war.

It is just part of the price we are all paying for 22 years of political schizophrenia. So our visit is really no more than a modest contribution to the cause of human sanity.

-

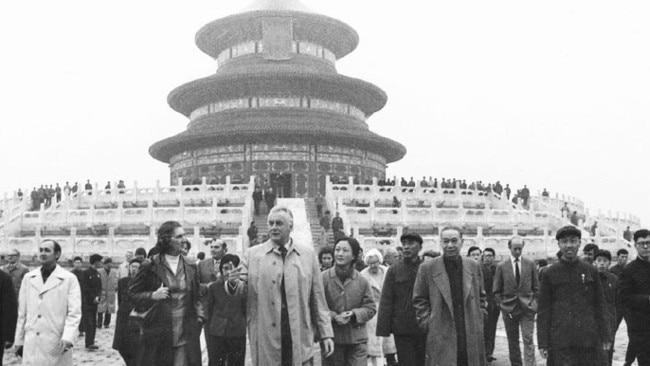

During his 1971 trip Gough Whitlam filed a series of articles for The Australian about what he saw, and why he believed so passionately in the need for Australia to develop a relationship with China. They are remarkably resonant today.

Read them here:

Whitlam’s Dateline Peking: Labor’s leader reports from China

-

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout